Dr. Suzanne Topalian, professor of surgery and oncology at Johns Hopkins Sydney Kimmel Cancer Center presented a paper at a recent ASCO meeting which caused quite a stir in the kidney cancer community. Her short talk is in the link below, with the transcription to follow.

What’s the good news about being anti? The complex interplay of our immune system and the manner by which cancer escapes its notice is a challenge to the researchers, but this trial shows that there are many ways to interrupt the growth of cancer cells. This trial and another mentioned offer new hope to patients who have already exhausted earlier options.

Not only did this trial show that this drug could provide relief to some patients with kidney cancer, lung cancer and melanoma, the presence of this anti-body may serve as a biomarker, and may predict which patients might respond to the drug treatment. Another step forward and more hope for all of us.

Anti PD-1 (BMS-936558, MDX-1106)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ij_hq_52K7M

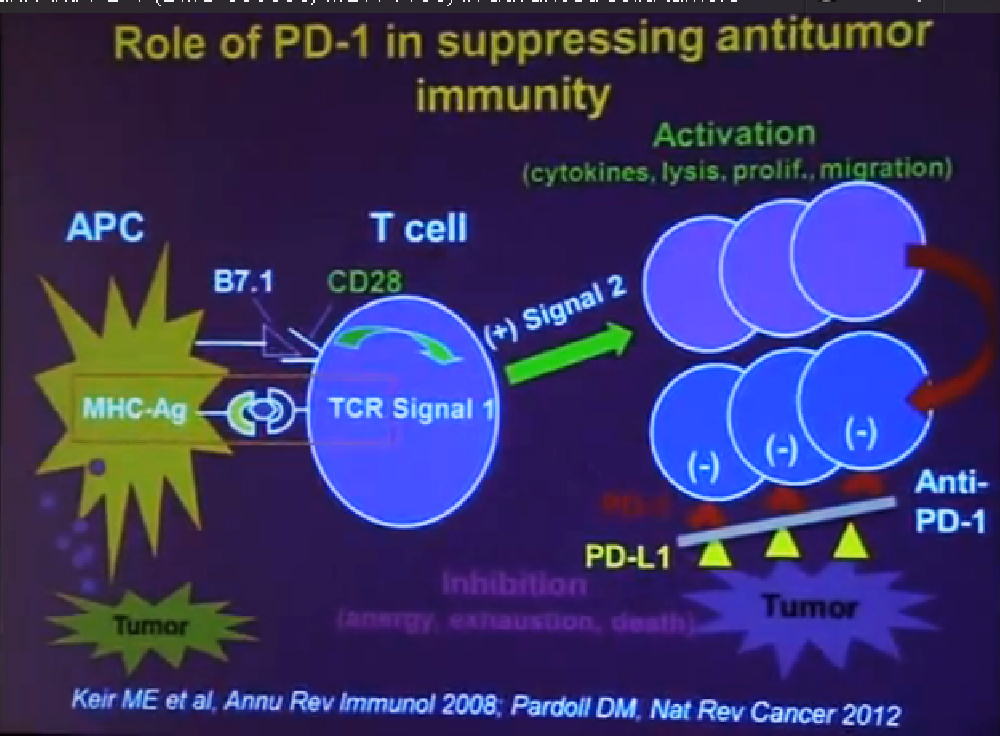

Today I would like to describe do the clinical activity the safety and potential biomarker of clinical response to the drug PD-1, which is an anti-body therapy. PD-1 or Programmed Death-1 is a molecule that is expressed on the surface of activated immune cells it plays a very important role in suppressing the tumor by suppressing antitumor immunity.

In order to understand how anti-PD one works you need to understand a little bit how the immune system works, and how it can fight cancer. T-cells are a central cell type in the immune system that fight cancer. T cell function is regulated by two different signals. Signal one is a specificity signal, whereby the T cell recognizes its target and here we are talking about the targets being components of tumor Cell., but then you need a second signal to tell, the T Cells what to do, a regulatory signals. That signal can be either positive or negative.

If the signal is positive or stimulatory, t he T-cells become activated. They secrete cytokines. They can kill tumor cells. They proliferate; they percolate throughout the body, seeking out and destroying tumor cells. All of that is what we want to see.

But after activation, T-cells naturally begin to express the molecule PD-1 on their surface. This is will turn the T-cells off. If they encounter the partner molecule PD-L1 or PD ligand 1, tumors cells can express PD-L1. So the interaction between these two molecules becomes a protective shield, that shields the molecule from immune attack. Even if the T-cell can recognize the tumor and they can get to the tumor, once they get there and they are expressing PD-1, if the tumor is expressing PD-L 1, the T-cells will be turned off. The anti-PD-1 antibody is a blocking antibody to PD-1. It interrupts this interaction and functions to rescue exhausted T-cells and to enhance anti- tumor immunity.

The phase 1 trial of anti-PD-1 that I’m describing today is a multi-dose regimen in which something is given the outpatient in the outpatient clinic once every two weeks. Patients were treated for a cycle of four treatments over eight weeks. At the end of which, they were restaged. Patients were eligible for these trials if they had advanced metastatic melanoma, kidney cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer with progressive disease after having had at least one prior systemic therapy.

But they were allowed to have up to five of the therapies. Generally these patients who came on this trial had good performance tab status. But they were heavily pre-treated. Approximately half of them had at least three prior therapies be before they came onto the trial.

After the first cycle of treatment if patients had rapid continuation of disease or clinical deterioration, they went off study. If they had unacceptable side effects, the patient remained on study. They did not receive any more drug, but they continued under observation. If the patient demonstrated tumor regression or stable disease or even if they had some progressive disease, but were clinically stable, we continued to treat those patients until we saw confirmed Complete response, worsening or progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity. We could treat patients on this trial continuously for two years. After, they went into a follow up phase.

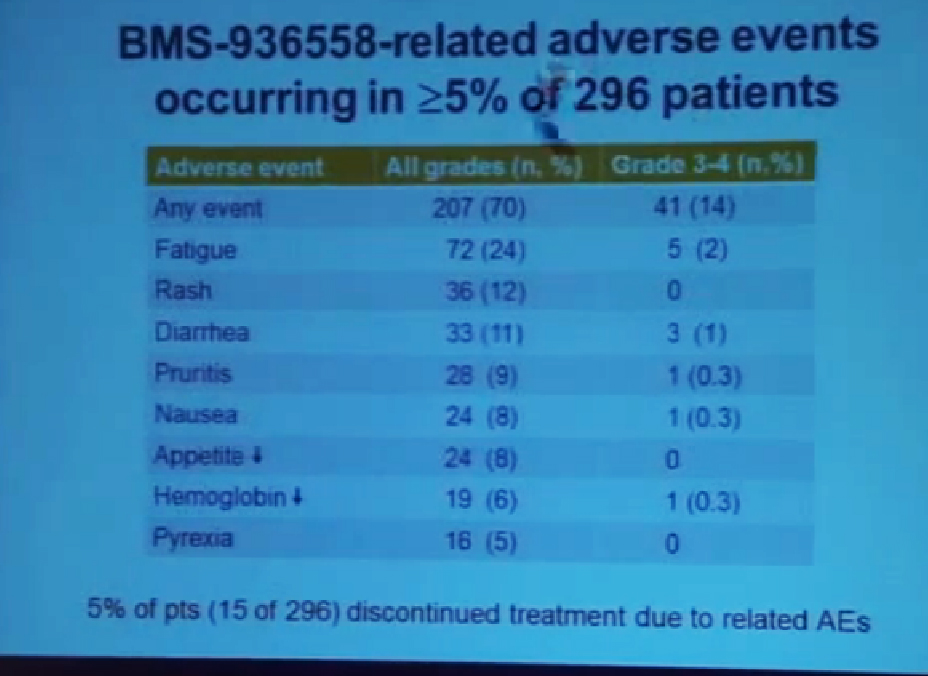

Here I’m showing you the drug-related adverse events are side effects that occurred in at least 5% of 296 patients which was the total patient population on this trial You can see that serious side effects were encountered in 14% of the patients. The most common side effects are listed here (fatigue, rash diarrhea, pruritis, etc.) There other side effects that are not listed here because they occurred less frequently. Many of the side effects were consisted with the side effects with over immune related causality as you might expected if you release the brakes on immune responses. As we are seeing anti tumor responses, you might also see immune-related sided effects.

Here I’m showing you the drug-related adverse events are side effects that occurred in at least 5% of 296 patients which was the total patient population on this trial You can see that serious side effects were encountered in 14% of the patients. The most common side effects are listed here (fatigue, rash diarrhea, pruritis, etc.) There other side effects that are not listed here because they occurred less frequently. Many of the side effects were consisted with the side effects with over immune related causality as you might expected if you release the brakes on immune responses. As we are seeing anti tumor responses, you might also see immune-related sided effects.

We did see three treatment related deaths on this study. This was in 1% of the patient population due to pneumonitis, or lung inflammation which we’ve believe has an immune-related etiology. Over the course of time we developed better ways to identify people who are at risk for the side effect and also better ways to detect it early on and to treat it aggressively.

Also note that only 5% of all patients treated on this trial had to discontinue treatment, due to related side effects so in general the treatment was well tolerated in an outpatient setting, and in general the side effects were manageable.

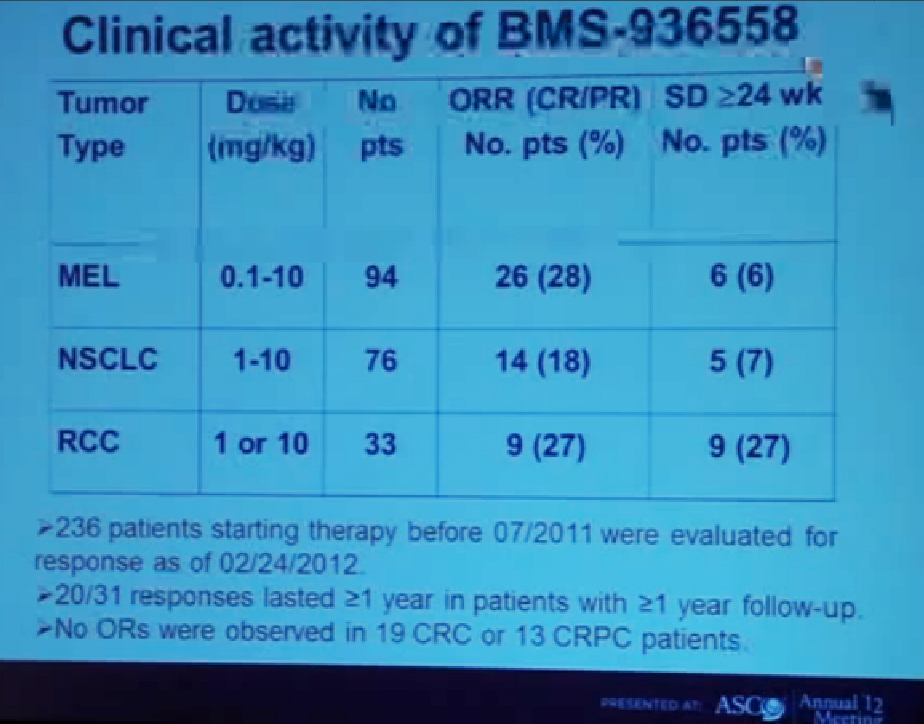

This is showing the clinical activity of anti-PD-1 antibody in three different types of cancer across a wide range of doses. (Showing doses (mg/kg) of 0.1-10 for melanoma, 1-10 for lung cancer, and 1 or 10 in RCC). The largest number of patients in this treatment population of 236 patients who had at least six months of follow-up were 94 with melanoma. We had 26 patients (28%) who had objective responses. An objective response means either a complete response or a significant partial regression of cancer.

We also saw stable disease that lasted at least six months in another 6% of patients. Among lung cancer patients we saw patients with squamous as well as non-squamous subtypes we saw a CR plus PR of 18%, and with a patient population of 76 and again 6% with stable disease, with another group of patients with stable disease (referencing 7% of lung cancer patients.)

Finally in kidney cancer (33 patients), 27% had a response rate and 27% who had prolonged stable disease. There were 31 patients on this trial who had a response that occurred at least one year ago and among those 31 patients, two thirds of them had a response that persisted for more than one year. One of the remarkable features about this therapy is that it can induce very durable responses in otherwise treatment-refractory patients with advanced disease. We did not reserve any objective responses in 19 colon cancer patients or 13 prostate cancer patients.

Finally I’d like to draw your attention to a possible molecular marker that would allow us to predict which patients are most likely to respond to therapy.

In a subset of 42 patients on this trial, we examined pre-treatment tumor biopsies for presence of PD-L1—and again this is the partner molecule to the PD-1 that is expressed on tumor cells. What we found was a correlation between the expression of PDL-1 on tumor cells and here I am showing you the pre-treatment staining biopsies.

I am showing you with its ringed expression an example of melanoma, kidney and cancer in a sample of lung cancer. When we saw this kind of expression in that group of patients we had a 36% objective response rate. If we did not see that expression on the surface of tumor cells we did not had no responders. I would stress that these are very preliminary data but give us an important lead for further investigations and potential biomarker development.

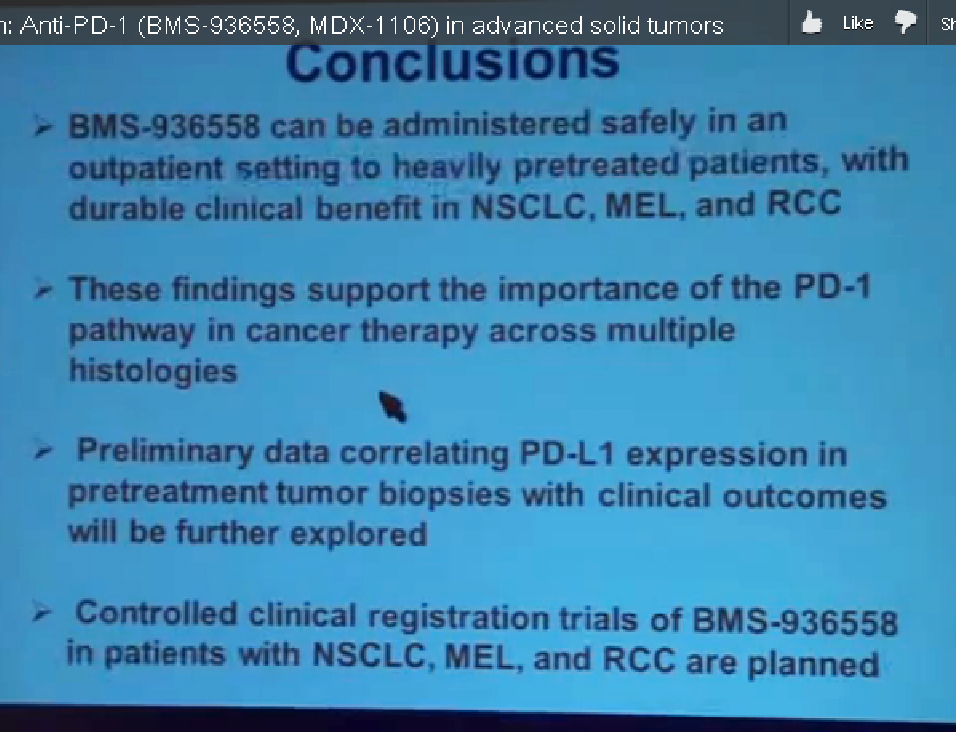

In conclusion anti-PD-1 antibody–BMS 936558– can be administered safely in an outpatient setting for heavily pretreated patients with durable clinical benefit for patients with lung cancer, melanoma and kidney cancer.

These results will be released tomorrow, as you know in the New England Journal of Medicine, which is under embargo until early tomorrow morning. At the same time in the New England Journal, there’s a companion paper with the blocking antibody against PDL-1. The lead author of that paper here is Dr. Julie Braemar of Johns Hopkins and shall be available to answer questions at the end of session.

We found responses also in melanoma and lung cancer and kidney cancer with a blocking antibody against PD-L1, so we feel these two studies are in a sense bookends to point up the point the importance of the PD-1 pathway in cancer therapy across multiple histologies.

The preliminary data correlating PDL-1 expression in pretreatment tumor biopsies with outcomes needs to be further explored and that’s an area of active investigation. Finally controlled clinical registration trials of this drug with patients with the three types of cancer that seem to respond are planned. Thank you for your attention.