I am presenting for Dr. Bukowksi (of Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute) and this is his outline. It is not so much about novel therapies, but about clinical trials, why they are important.

Clinical trials, what’s in it for you? We talked about it for the field, but what is in it for the patients who might want to consider a trial? What is a clinical trial?

“A study conducted to allow safety and efficacy data to be collected for a health intervention such as a drug, device, or treatment protocol”, as per the slide.

They are designed on a certain ethical code of conduct which we follow very closely. They are monitored very closely, followed by people, both internally and externally, the FDA and IRB, the Institutional Review Boards at our institutions.

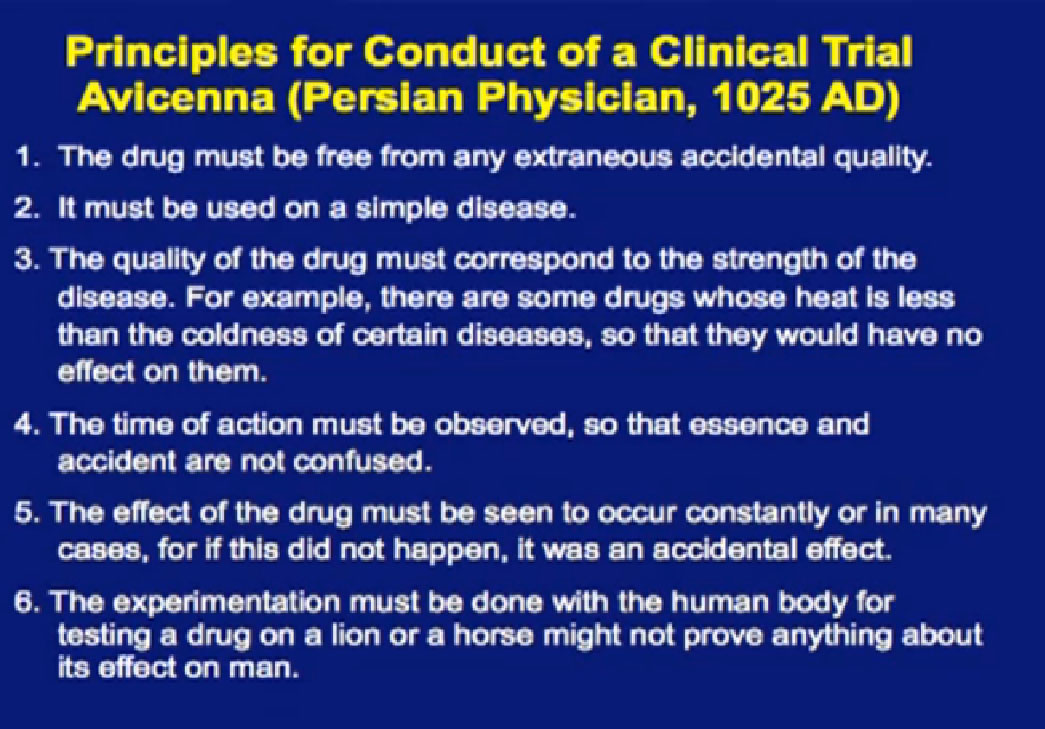

This list– I thought this was pretty funny– that Dr. Bukowski came up with is from a Persian physician, on the ways to conduct a clinical trial, from 1025 AD, a thousand years ago. I don’t know how many clinical trials were done a thousand years ago, but I thought the last one was pretty good, “The experimentation must be done on a human body, for testing on a lion or a horse may not prove anything about its effect on man.” We talk a lot about morbidities or complications on people on clinical trials; I can’t imagine being the investigator on any lion trial! Probably higher risk for the investigators than the lions. I’m glad we made advances in the last thousand years.

This is one of the more famous clinical trials, given by James Lind in 1747. He was given the task, and first to show that citrus fruits could cure scurvy. He did what was like a randomized trial, comparing the effects of various acidic substances, citrus fruits or cider– gave them to sailors with scurvy, essentially proving that giving oranges and lemons can give quick recovery in patients with vitamin C deficiency. He is one of the founding fathers of our field of clinical investigations. We’ve come a long way since then.

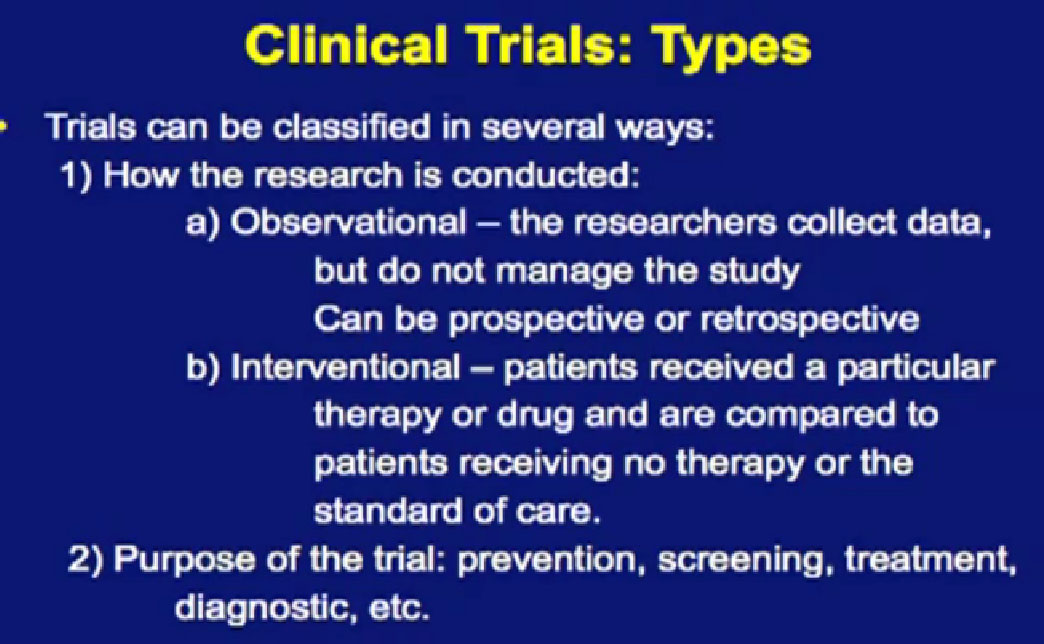

As far as types of clinical trial, some are conducted in different ways. Some are what we call observational, meaning we collect data that other researcher use to study patterns, to study outcomes over the long period time, things like risks for heart disease. For this group, we often do something for patients, usually with a device or a therapy, and this usually compared to a group receiving no therapy, no treatment, or commonly, the old standard of treatment of care.

There can be many different purposes for trials. Some can be for screening, some are preventative, which we haven’t talked about much yet, but can improve the way we diagnose kidney cancer. So there are many different types of trials.

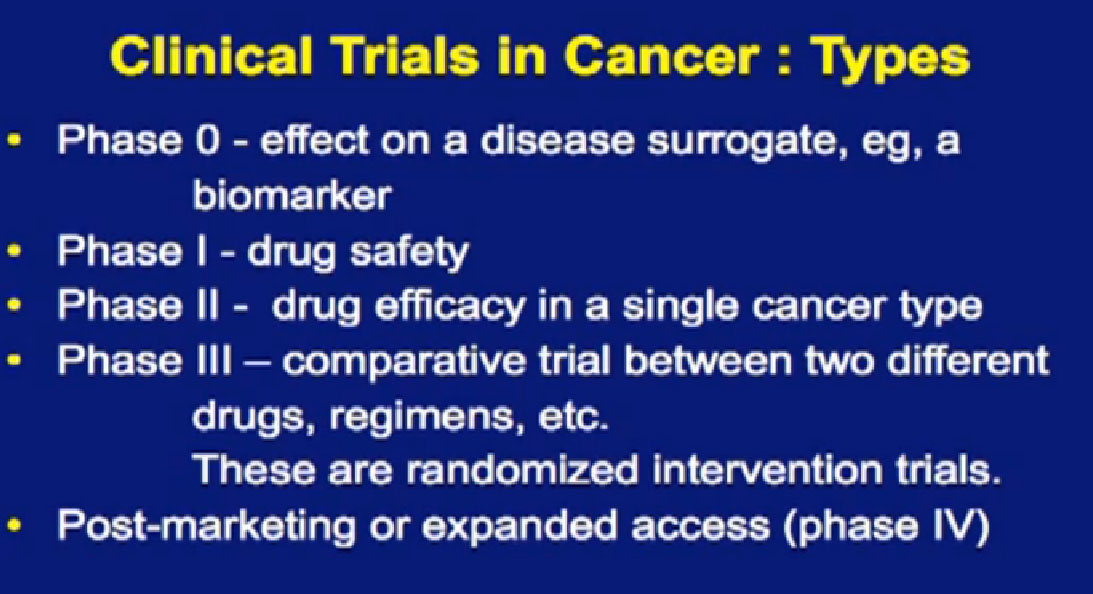

You want to ask, “What phase is this?” The reason that is important is that each phase of testing has a different goal. I will focus on the middle ones here; Phase I often focuses on the drug safety. It has traditionally been about, “What’s the right dose of the drug? What’s the right schedule for the drug?” Traditionally, Phase I trials have not always been great for the patients, as the main focus is “What’s the safest way to give the drug?”, not whether the drug is effective. They were often left for patients with fewer or other options, when everything else had run out, you would consider a Phase I trial.

But nowadays, Phase I trials are changing somewhat. They are often not open for patients with just any kind of cancer. They are open for patients with specific kinds of cancer, because there is already some sense that this drug looked interesting in the laboratory, that it might be effective for a specific type of cancer. W aremore focused in that regard. We are also testing patients for certain tumor characteristics, so getting a sense, not of what kind of cancer they have, but what kind of tumor do they have, what kind of genetic changes are going on in that tumor. Most importantly, some phase I trials—once they get the safe dose—are doing what is called “dose expansion”, where they take patients with specific tumor types and treat them all with the same dose. This is essentially doing a Phase II trial within a Phase I trial, though a smaller Phase II trial. In many ways, there is an advantage on the being on that kind of trial, in my admittedly biased opinion, because you know you are getting a drug that has shown in many cases some sense of safety and activity. It is certainly something you should consider, not necessarily right off, just because your doctor wants to consider you for a Phase I trial.

Phase II trials’ main focus there is the effectiveness; how effective is the treatment? They usual focus on some single cancer type.

Phase III trials are a more comparative trial. It’s comparing something that is new to an older or the standard treatment. For many years, the “new” was really no better than the old, but one of the things that more recently, is that a lot of the new has been better and we often have had a sense that it was better, before we got to confirm it in trials.

One of the uncomfortable things about a Phase III trial, from a patient’s point of view is the randomization. It makes them very anxious. You lose a certain amount of control, both the physician and the patient, about what you are going to receive. So a lot of people choose not to go on a Phase III trial because they are uncomfortable with that process. The way I like to look at, not as a patient’s perspective, even in a randomized trial is that you get a 50% chance at trying a new agent earlier. That may not be worth it to you, but it’s worth a discussion, a consideration as you go through treatment. There often are also trials that come after the drugs has been approved, like expanded access trials, where they offer it to patients just to test further questions, safety, for example.

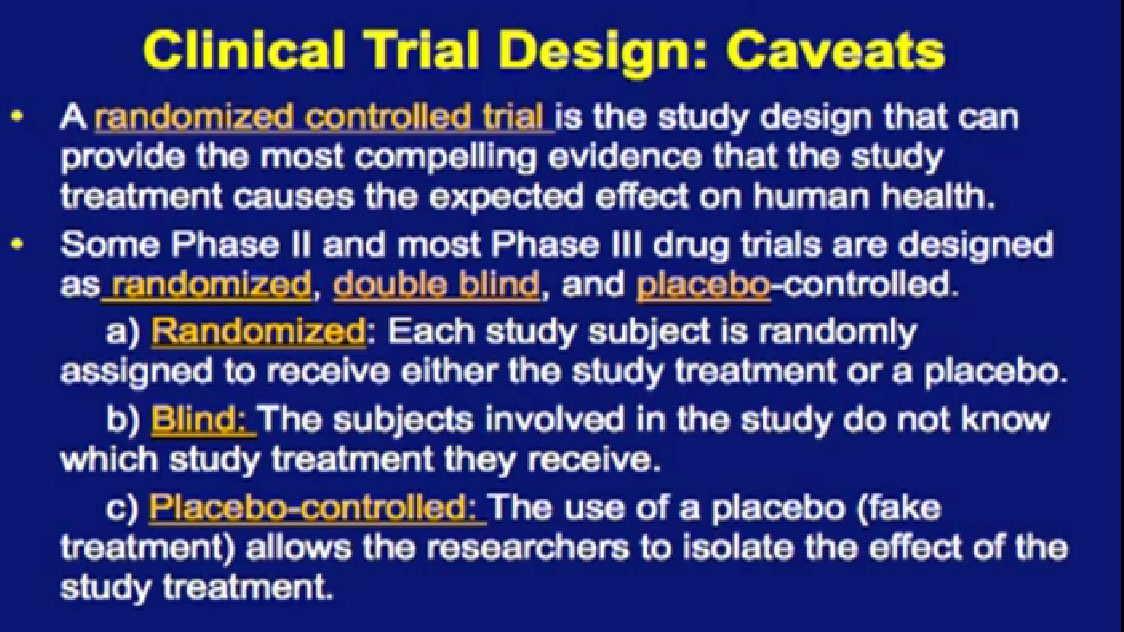

We talked a little bit about clinical trials, and some of the caveats, about randomized trials and how that can throw people off. Like randomization: It turns out that this is the only way we know if a new treatment is effected. As many flaws as there might be from a patient’s perspective, it is here to stay. At least for the time being, we are going to have randomized trials.

One other concept that often also throws people off is whether the trial is blinded, that is, where the researcher and the patient may not what the patient is getting. Why is that? The reason is that because if you know what someone is receiving, you might make judgments that bias the outcome, both on the patient’s side and the physician’s side. A lot of people don’t like not knowing what they are getting.

PLACEBOS

The one thing that throws the most wrenches into this is the whole concept of a placebo as a control arm, and unnerves a lot of people for good reason. You are going to to be told if a placebo is involved, number one, for sure, up front. Now that we have effective drugs, placebo-controls are less likely to be acceptable options. Meaning, they are only acceptable if there is no standard treatment, so 5-6 years ago, when there was no or very few standard treatments for kidney cancer, we relied on placebos.

Now these are being compared to active treatments. So you are either getting active treatment A or active treatment B, comparing it to a new treatment. Going forward in kidney cancer, there will probably be fewer and fewer placebo-controlled trials.

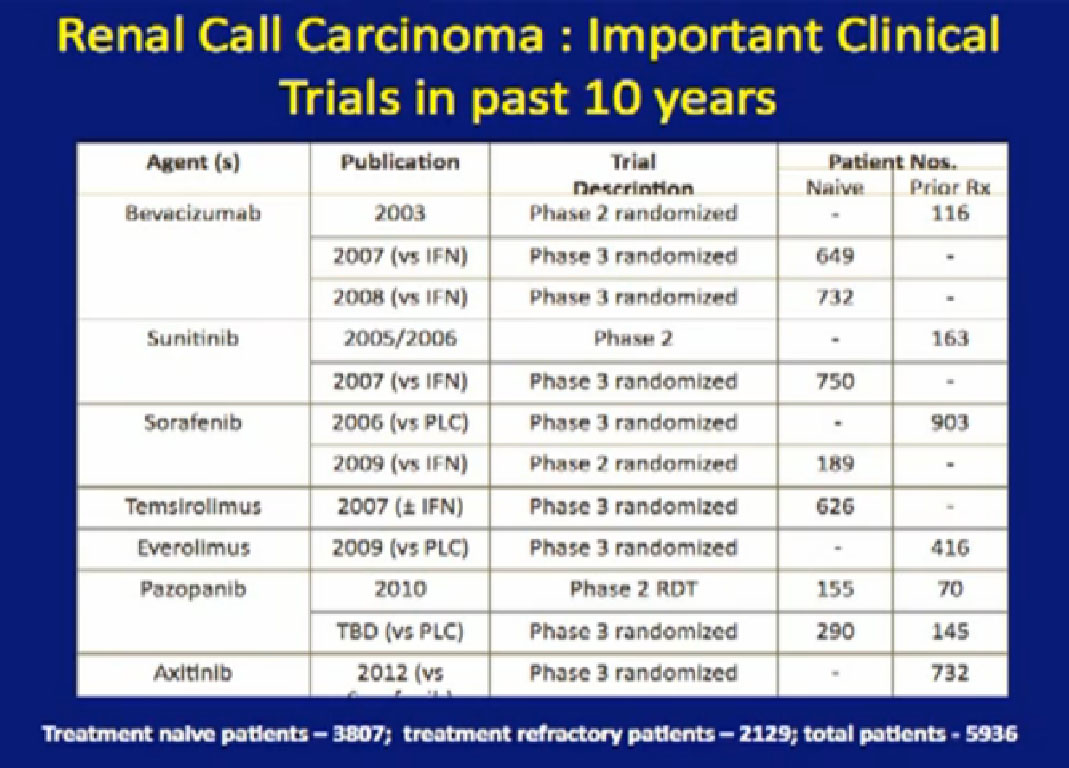

Here’s a list; you’ve seen this before; all the important trials that they have done in the last ten years. The important thing about this is that is patient involvement that has made this progress possible. This is a look at 8-9 trials that have enrolled 4000-5000 patients. It is quite a long list of progress, made only by patients with a willingness to so, so it is important to encourage people that you may communicate with online or in your email to consider participation. It is only through that participation do we make this kind of progress. Clearly we have more progress to go.

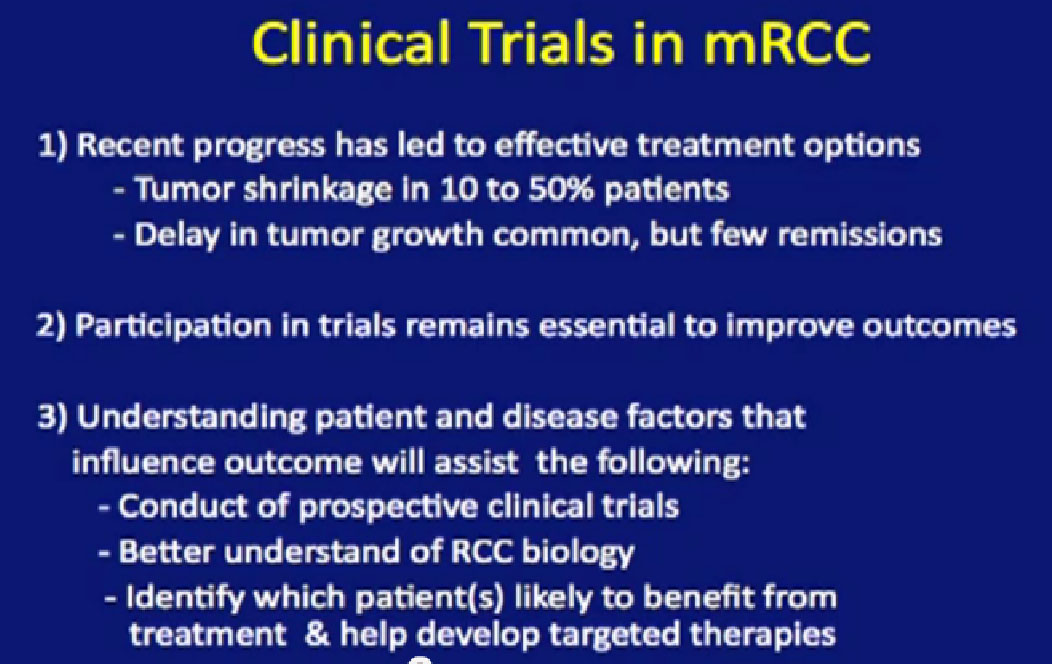

So summarizing our recent advances, to show that we can shrink tumor in 10% up to 50% of patients in these newly targeted agents. As Dr. Jonasch was talking about, we can surely slow tumor growth which leads to lengthening of survival. Patients are living longer, Hutson says 3-5 times longer. My patients are living years longer than they used to in the past, but we are still not receiving enough remissions. We need to work on getting remissions, once the treatments have stopped.

We talked about participation, we need to do that to improve outcomes. We need to better understand the biology of kidney cancer, as Dr. Jonasch was talking about, to identify patients before they get treatment, and to assign them to treatment that is likely to help them. It is only through that–not just clinical research, but also laboratory research– that we will be able to do that in combination. We need to increase the funding for those endeavors, as it is rather expensive, at a time when the NCI’s budget is fairly tight.

You hear a lot about personalized medicine in the treatment of cancer, but we are not yet in the era of personalized medicine for kidney cancer. We are making certain decisions, but they are based on fairly rough guidelines, but we are making decisions based on whether a patient has been treated or untreated. We are trying to assign to patients to certain risk categories based on certain features of that suggest a good or a poor prognosis. We are making decisions, as we talked about earlier, on whether a patient has clear cell or non-clear cells, but these are very rough sort of guidelines. We need better ones, obviously and we are hoping to come up with better ones, based on the patients’ own genetic profile and the profile of the genetics of the tumor. There is a lot of work going on in that as we speak.

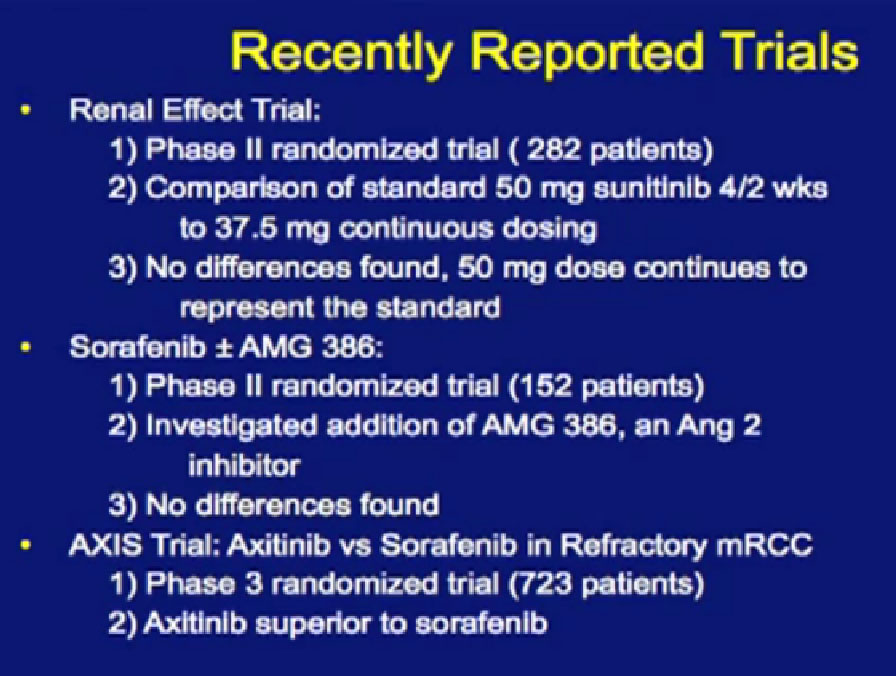

Recently reported trials; these are trials reported in the last year.

Not all trials are positive. The first is called the Renal Effect Trial, randomizing patients to either prescribing the intermittent dosing of Sunitinib versus the continuous dosing of Sutent. The hope was that giving the drug at a lower dose continuously that the treatment would be more tolerable or more effective. It turns out that there was no difference, so they could be used interchangeably.

There was a second trial with Sorafenib, where they added on another anti-angiogenesis inhibitor, in hope of improvement with the standard drug, Sorafenib. It’s the trial in the middle there, and unfortunately, the additional drug did not improve outcomes to the Sorafenib.

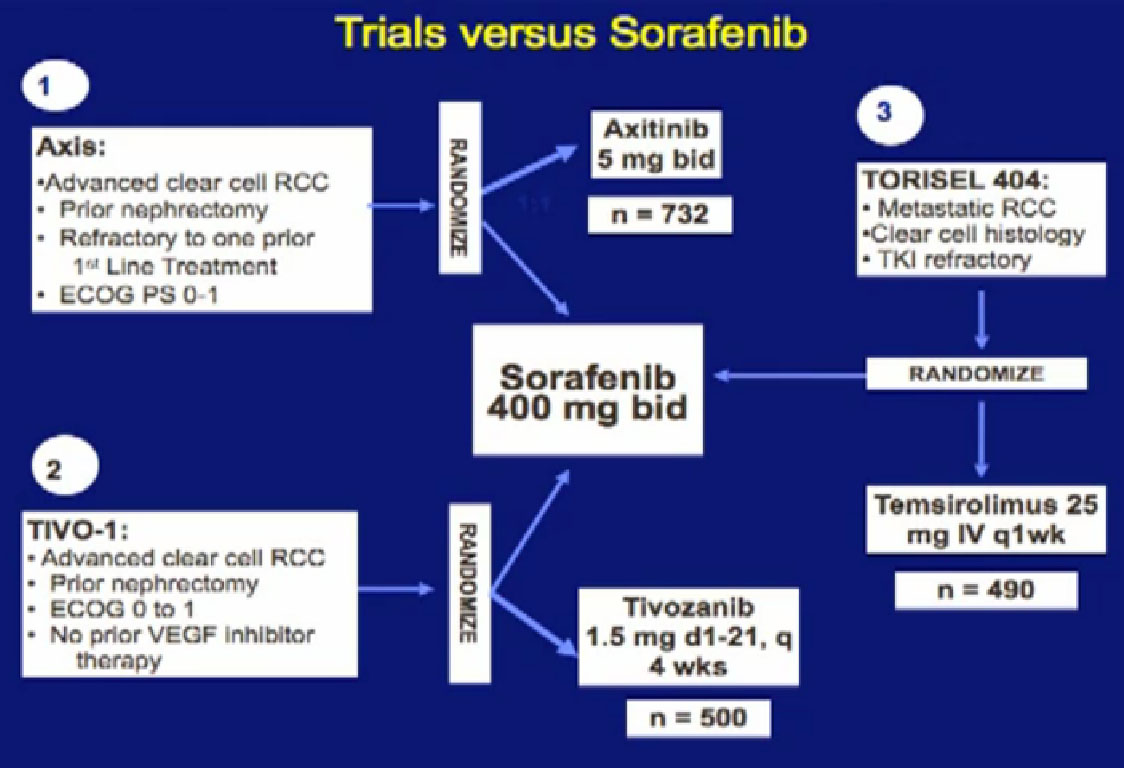

The last trial on the bottom, that both Dr. Hutson and Dr. Jonasch mentioned was a Phase III trial, once again a randomized trial that comparing—not a placebo—but a standard of care, Sorafenib to a new therapy, axitinib, which proved clearly that axitinib was a step forward. It may be a small step forward, but it is important for our patients. That led the FDA to approving this new, hopefully, second generation anti-angiogenesis drug for our patients earlier this year.

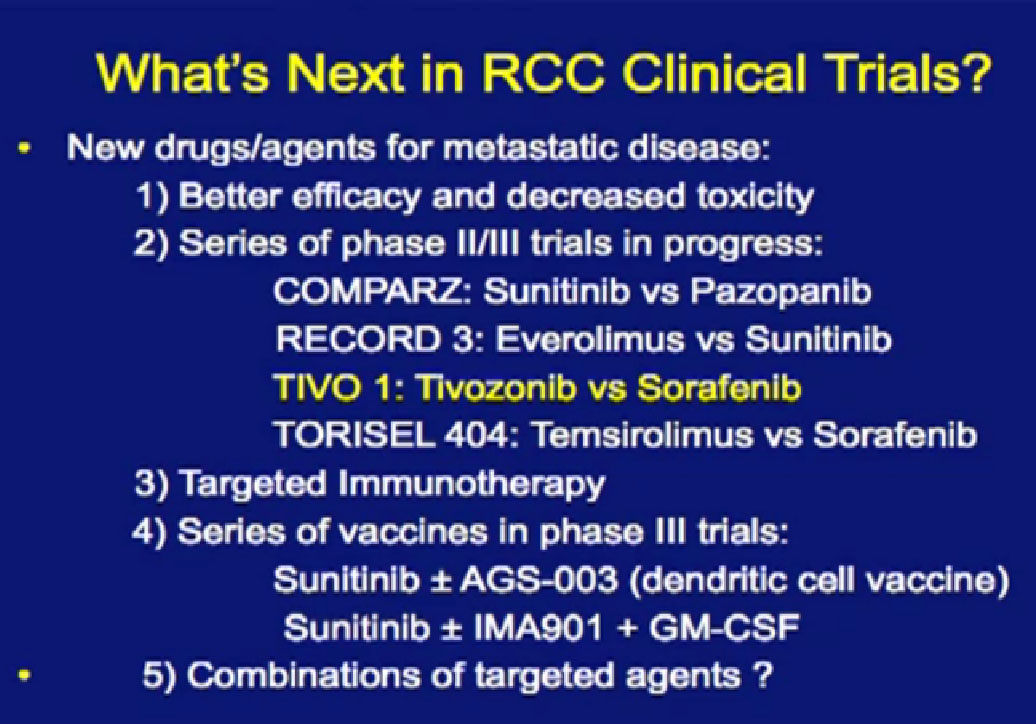

So what’s coming? Hopefully, drugs that are less toxic and more effective. There are a series of Phase II and III trials that are coming close to reporting their results you will be hearing about them in the next year.

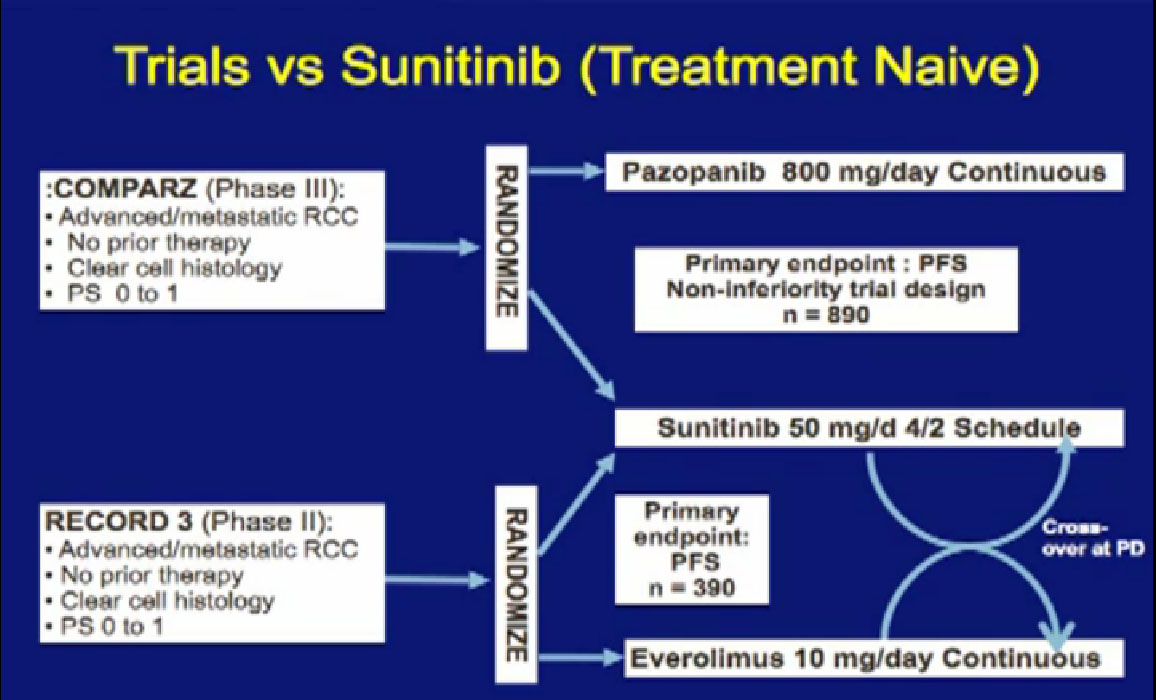

Their names you see here: COMPARZ, RECORD 3, TIVO1, you’ve heard a bit about, TORISEL 404. We talk a little bit about these, what we can expect from these trials. We can also talk a little bit about targeted immunotherapies, vaccines and ultimately, combinations that might make sense. All these are being tested and in the next year, we’ll know a lot more.

There are several trials, trying to improve upon Sunitinib, which is the most prescribed treatment for patients with metastatic kidney cancer in 2012. The COMPARZ trial is comparing Sunitinib with Pazopanib, which is Votrient. The makers of Votrient would hope show that it is as effective as Sutent, and perhaps less toxic. We’ll see that result later this year. Obviously, drugs that are less toxic are worth developing.

The other trial looks at the proper sequencing of the RECORD trial. Should you start with Sutent and move to Afinitor, or start with Afinitor and then move to Sutent? We should get some information on the proper use of Sutent, hopefully, with the RECORD 3 result

We mentioned the AXIS trial which compared axitinib to Sorafenib and led to Axitinib’s approval. That was a step forward.

Hopefully there will be another step forward in the second line setting, which is this new -1, a second generation of anti-angiogenesis inhibitors. This TIVO-1 trial which Eric (Jonasch) mentioned targets a new, more specific antiangiogenesis inhibitor , comparing Pazopanib to Sorafenib, showing it was more effective, so once again, we are coming with better agents than five year ago.

Another important trial will compare an mTOR inhibitor to Sorafenib again, Torisel to Sorafenib standard and to answer the question, when you fail a prior treatment like Sutent, what is better—to give you a another drug like Sutent, or to give you a completely different approach—which is the Torisel drug. We’ll be learning a little bit more about the proper sequencing of these agents. All of this information should be available coming soon.

The Tivozonib data will be presented at ASCO in June and hopefully the Torisel data will be presented later this year.

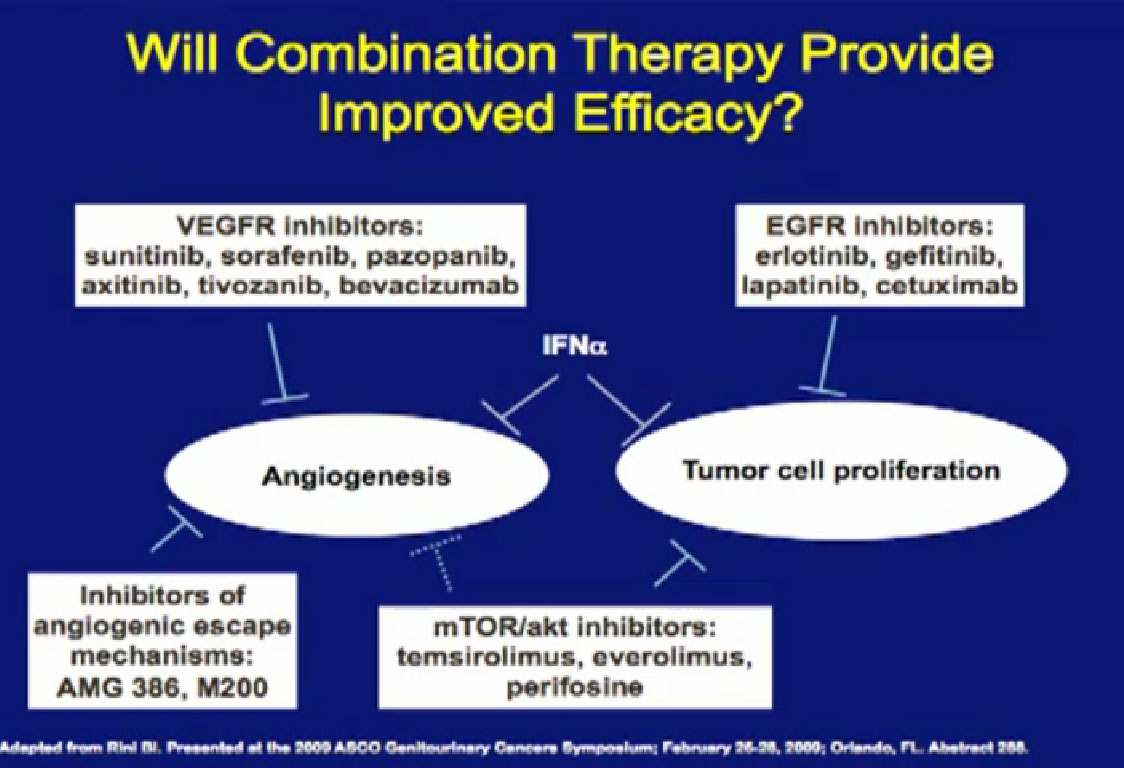

Combinations of drugs; most oncologists think that if one drug is good, two have got to be better. There have been a lot of combination trials done this far. Most have been, I must say, somewhat disappointing, and we will talk about why that is. Hopefully, as we get less toxic agents, we will bet smarter about putting these things together, and we will make some progress. These are some of the drugs that have been used in combination.

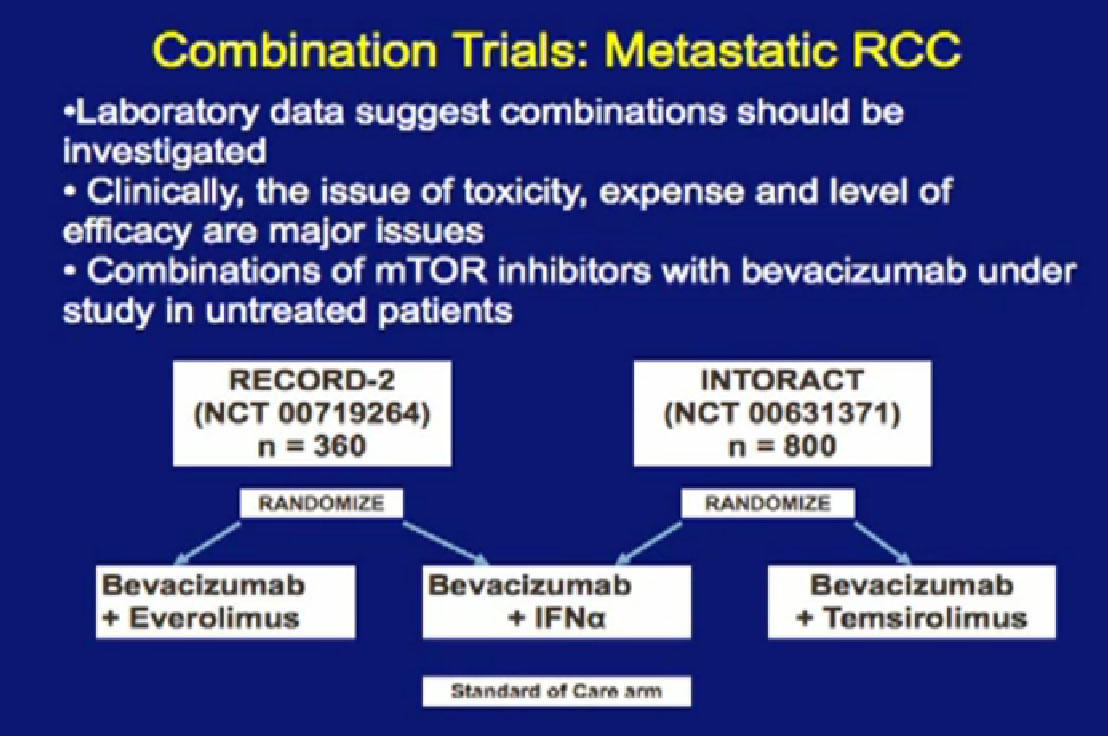

Laboratory trials have suggested these: we don’t just do these willy-nilly. Laboratory studies have often shown that two drugs are better than one, but there are several important issues. One of these is cost. You all know that these are not cheap. The other is toxicity, and so far, most of these combinations have proved pretty toxic when given together. Here are two trials that are looking at a blood vessel strategy with mTOR inhibitors. The RECORD 2 trial looks at Bevacizumab and Everolimus together versus the standard of Bevacizumab and interferon; the INTORACT trial looks at Bevacizumab and Temsirolimus together. These are both large trials that will give us the answer to whether two approaches to attacking the cancer better than just one at a time. We’ll see that going forward.

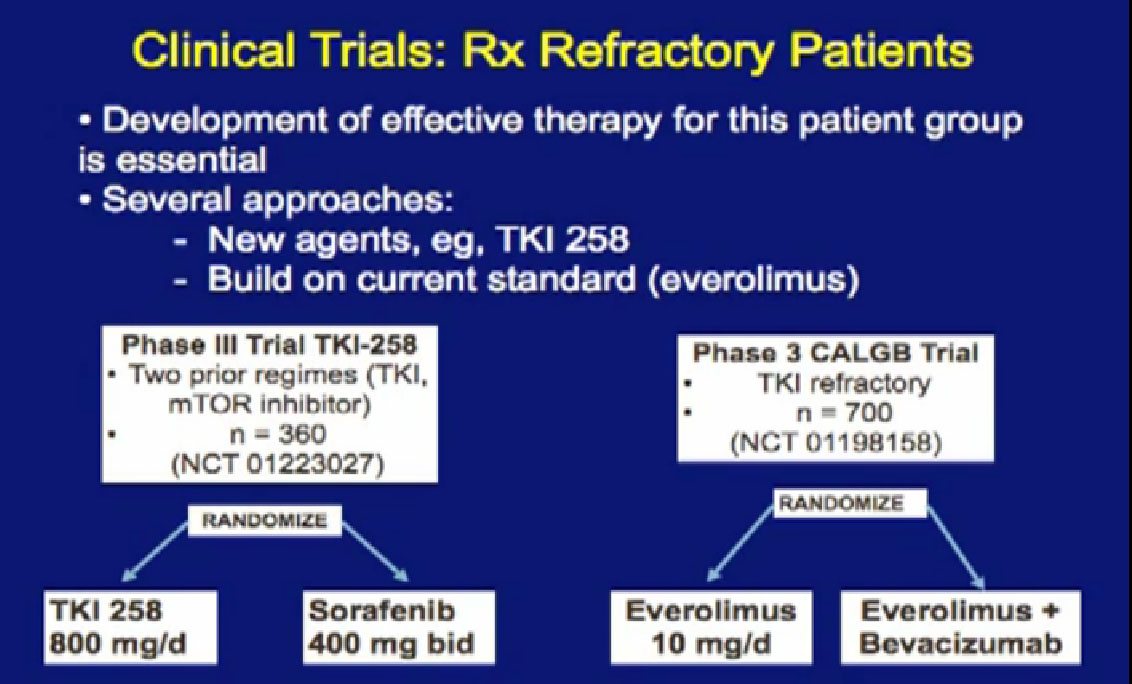

As you know, as we talked about things today, that none of/very few of these drugs produce complete remissions, and we obviously need second- and third-line treatments.

There are a couple of trials accruing that will give us some answers to that. There is another antiangiogenesis inhibitors, the TKI-258 (references on left), and it is in phase III trials, once again comparing to Sorafenib, so that might be a step forward as well. Looking at this Phase 3, looking at this Cooperative Group Trial, looking at combinations, adding Bevacizumab, hoping that will aid in outcomes with what Everolimus does. We’ll see.

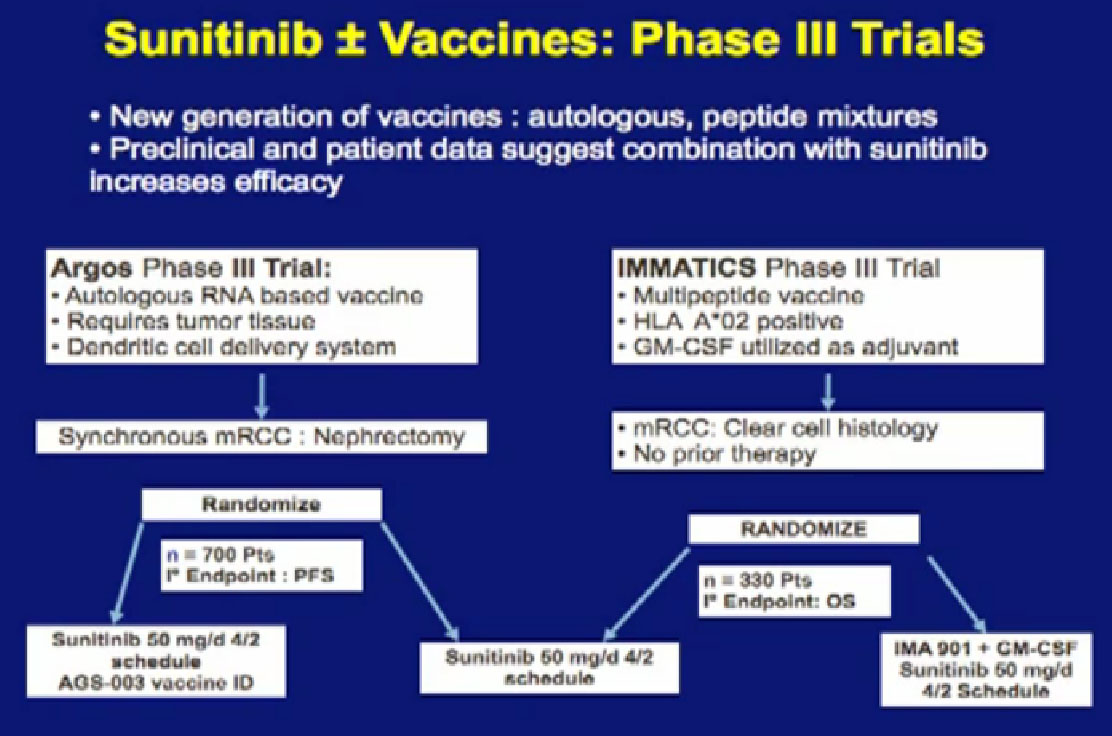

We’ve talked about vaccine treatments, and I alluded to one trial, the ARGOS III trial, looking at combinations of vaccine and Sutent. It is more than one trial, it is the IMMATICS trial on the right,; it looks at another peptide vaccine, also in combination with Sunitinib. Hopefully it will lead to more durable benefit with this drug. It is great that we are in large Phase III trials, as this will give us answers, but the answers are still a long way away, as these trials are still enrolling patients.

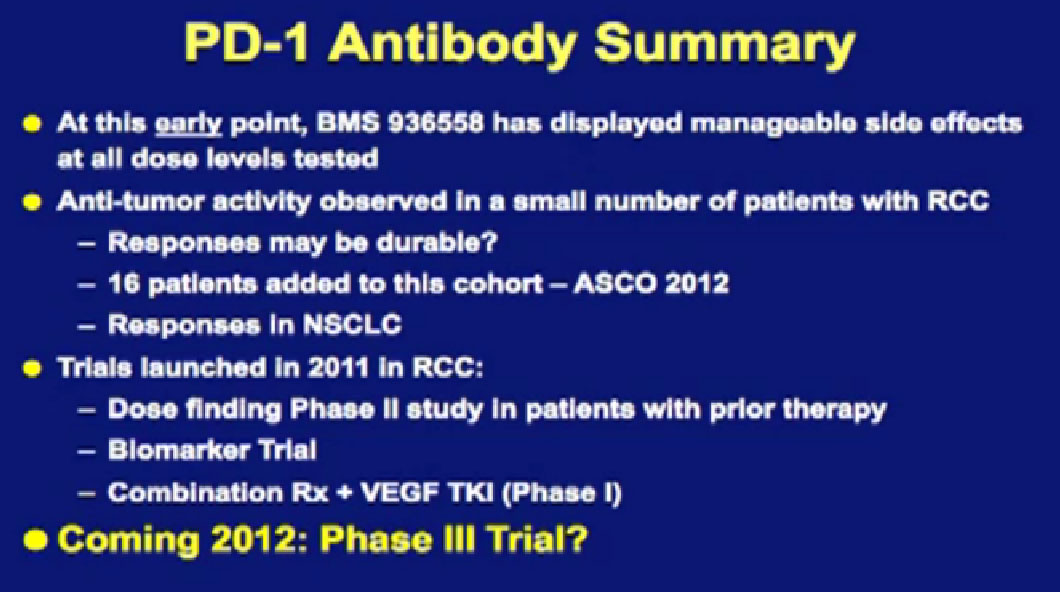

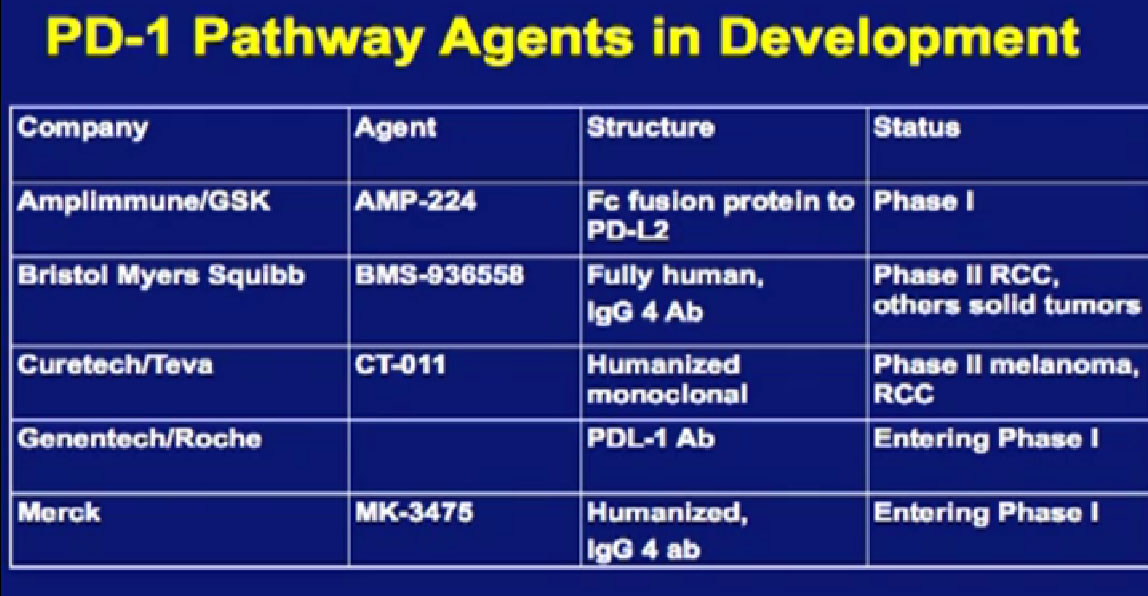

We mentioned the PD Antibody earlier. This is one of the more exciting ones of the targeted therapies being developed. Two things I did not mention this morning that I want to make now, is that this drug will soon be entering Phase III trials. It’s moving pretty quickly, and hopefully Phase III trials will open later this year, and if positive, might lead to the drug’s approval.

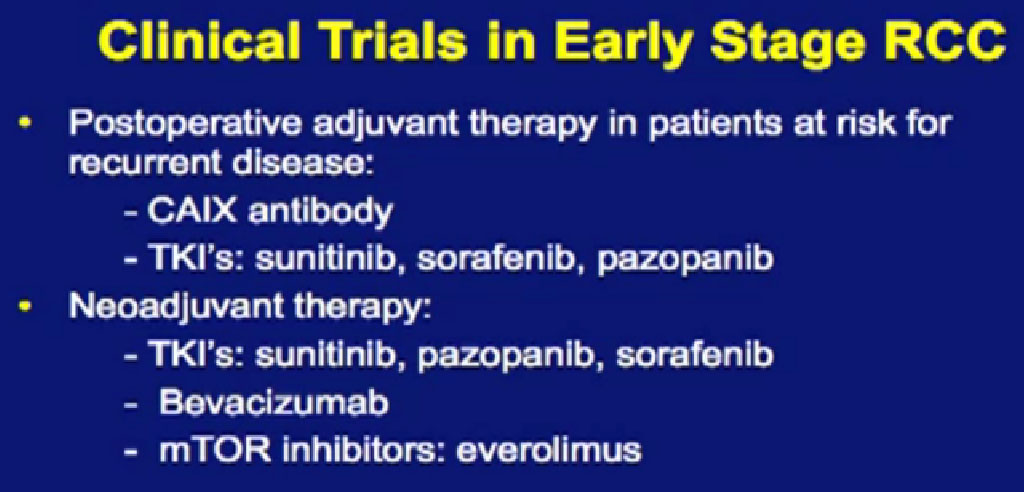

But just as important, there is more than just one PD or PD L drug in development. These are five separate companies, all of whom have decided it is important to find different way to block the “barbed wire” that I talked about, that protect cells from the attack by the immune system. You will hear more about these agents, not just in kidney cancer, but in other tumor types as the year goes on. Chris Wood covered this very well earlier, so I won’t address that, but we are also doing clinical trials with drugs that have been used with Stage IV patients, we are now using those with Stage II and III patients. And as he (Wood) said, it will take several years before we know if it will delay cancer from coming back after surgery, or will prevent cancer from coming back after surgery—there’s a big difference with those two. We are several years away from knowing those results. But the great news about these trials is that they are accruing well. Patients have gone on them very quickly, much more quickly that we expected, though the drugs may have issues for the patients, side effects…..we will have to see about the effectiveness. The patient community if very motivated to go on trials like this, so hopefully as we get better drugs, we can test them in patients in the early stages of kidney cancer and prevent recurrences. That’s where we can have a huge impact, preventing the need for treatment for Stage IV cancer.

Chris Wood covered this very well earlier, so I won’t address that, but we are also doing clinical trials with drugs that have been used with Stage IV patients, we are now using those with Stage II and III patients. And as he (Wood) said, it will take several years before we know if it will delay cancer from coming back after surgery, or will prevent cancer from coming back after surgery—there’s a big difference with those two. We are several years away from knowing those results. But the great news about these trials is that they are accruing well. Patients have gone on them very quickly, much more quickly that we expected, though the drugs may have issues for the patients, side effects…..we will have to see about the effectiveness. The patient community if very motivated to go on trials like this, so hopefully as we get better drugs, we can test them in patients in the early stages of kidney cancer and prevent recurrences. That’s where we can have a huge impact, preventing the need for treatment for Stage IV cancer.

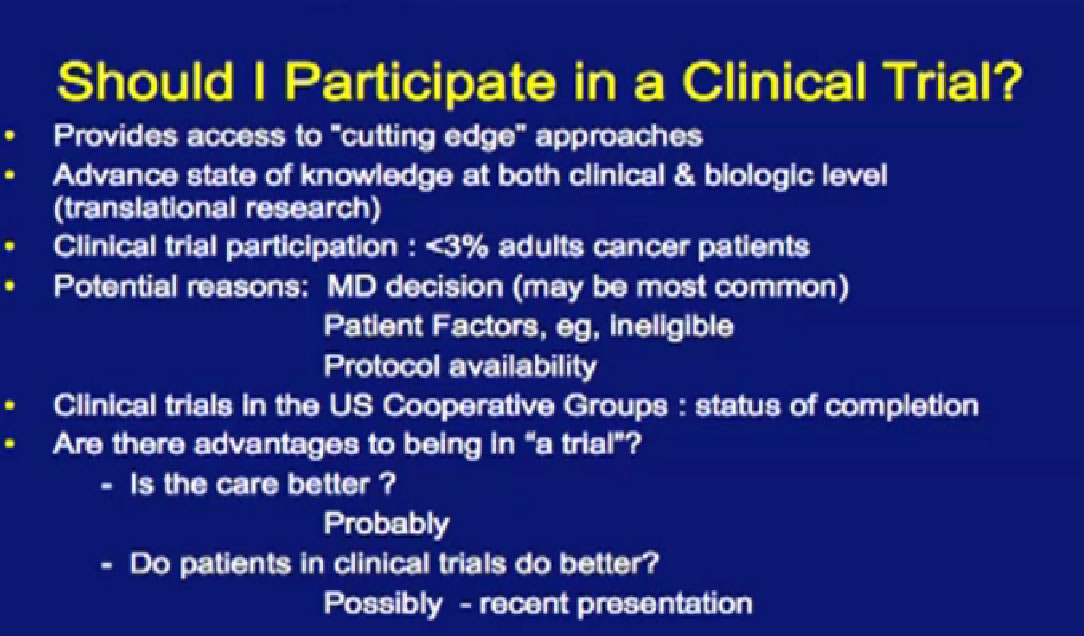

So, in closing this is obviously one fundamental question for folks who have not considered a clinical trial. Obviously I am biased, incredibly biased, as it is what I do. I think it gives you access to cutting edge approaches. Obviously the newest thing isn’t always better, and sometimes it is harmful and we’ve seen multiple cases of that. But I do think you get access to things sooner if you consider trials.

And I do think we are getting better, as I mentioned, picking treatments than we were ten years ago, and also picking patients for those treatments. We are a little bit smarter. We are having more positive trials.

But all that being said, the participation of patients in the US in clinical trials is still less than 3% of patients. So when you think about it, I can sit up here all day and talk about all the things I want to do, and Eric (Jonasch) has great ideas, and Tom (Hutson) has great ideas, and Chris Wood’s ideas are OK (smiling), but we can’t do it without participation and convincing people to come and sacrifice, as there are costs to travel and risks . It takes a lot and really requires a mobilization of the whole kidney cancer community. I hope that this will increase the willingness to participate in clinical trials to get the message out about why it is important. There a lot of reasons why you might want to consider it, but people ask, What else is in it for me?” I know what is in it for me, and for the field, but what else is in it for me personally?”

There are some people who think that the care on clinical trials is better. You can argue that back and forth, but you are certainly followed much more closely on a clinical trial that you wouldn’t be if you were not on a trial. You are not only being watched more closely for side effects, you are watched very carefully to see if the treatment is working. There are a lot of rules set up to protect you, not only from the side effects, but from ineffective treatment. There are rules by which we have to remove you from your trial if it is not in your interest. Most importantly, you can always stop at any time, once you join a clinical trial.

The other question which is a little bit harder to address is whether patients on clinical trials do better, and he has some interesting data

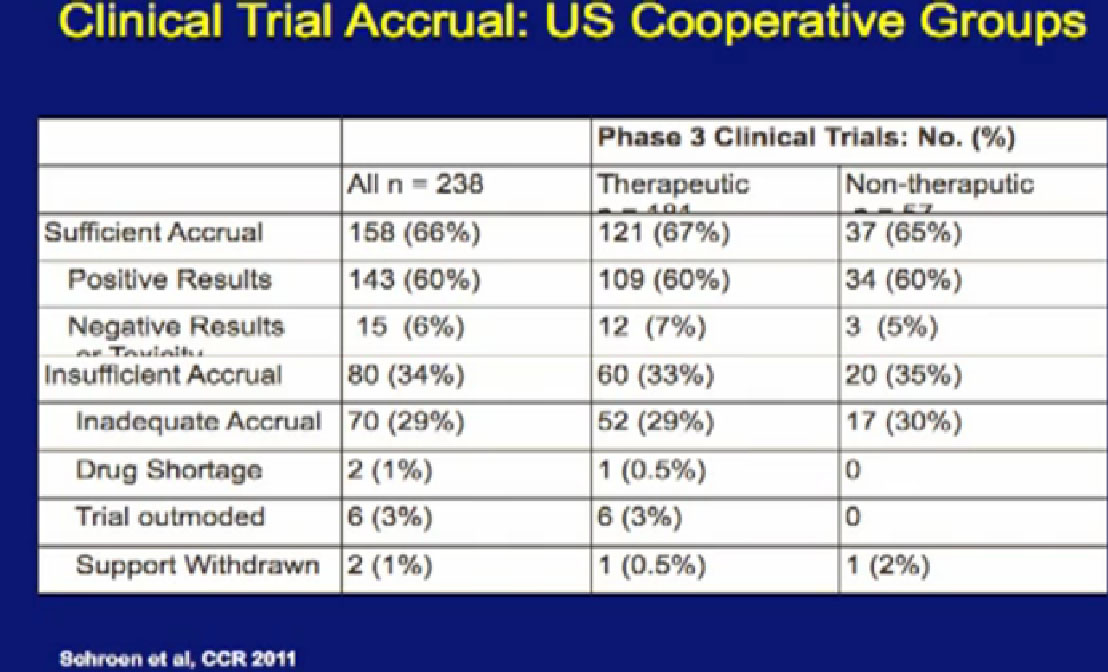

data that was presented last year. This is looking at 238 phase III clinical trials of all cancers done in recent years. When you look at this slide, and it’s a little bit complicated, I didn’t want to get too much data in it, but it is kind of important..

For the 158 trials that reached their goal, where they reached the sufficient number of patients, Sufficient Accrual, that was 2/3 of phase III trials. So not all phase III trials reached their goals of accrual of patients, which is a problem. But of those that did, most of those trials showed positive results, in fact, 143 of 158 had positive results. There were some that had negative results, closed early, or had side effect of toxicity. But it was a relatively small number, only 15% on this slide. The highest reason for trials not succeeding was that they did not get enough patients on them.

This makes a couple points. One, we’ve got to get more patients on trials, so we can answer these questions. Second, a lot of the trials that we are doing help advance the field, but we think help the patients who go on them. That would be hard to prove, but it is certainly worth considering. There may be some advantages for you as an individual when you are considering going on a clinical trial.

So in conclusion, clinical trials advance our knowledge and have improved outcomes in kidney cancer. It has been a great effort by many patients. Six thousand patients have gone on these trials that we have talked about over the day, not only improving outcomes for themselves, but also for future ways we treat patients. Coming up with better way to treat patients is only going to happen with research. We need to keep working on it, to define new approaches, we need to extend treatment earlier in disease, and we need to focus on patients who are unable, or don’t qualify for trials. We need to do a lot more work in that area, but hopefully, in partnership we can make advances, like we have in this last ten years.

End of Lecture; Questions from patients and caregivers follow.

Questions;

ACOR list member has asked about XL 184. How optimistic are you about XL 184 having activity in bone lesions, as well as soft tissue lesions; also, as far as imaging, she would be concerned about masking of bony lesions on imaging. On recent studies, ie, questions whether bone scans are the best measure of activity of XL 184.

That is a pretty sophisticated question, and in my earlier talk, I got a questions about XL 184 and I think this. In kidney cancer, it has only been through Phase I testing, so I think it is a little early to know how active it is. But there are really people in our community that really want to study it. The focus is not only the VEGF but the protein that Dr. Jonasch mentioned, that MET protein which is thought to be an important driver in all cancers, and kidney cancer. Certainly we want to study it. It’s been tested mostly in prostate cancer, and they’ve seen some impressive results. We’ve seen that in prostate cancer, but whether we will see that in kidney cancer, that remains to be proven. That would be an advance, something that would control bone metastases. That would be exciting, since a lot of our drugs fail in bone. But it would need to be tested. I couldn’t agree with that more. How well it will be tested, that remains to be seen. Dr. Tannir may be talking of this class of drugs in his talk.

Soft tissue metastases, any activity in that? I know we’ve seen activity with the bone mets, but soft tissues?

Answer: It is to early to say that we have seen that, but that is certainly the story in prostate but we don’t know yet in kidney cancer. But you will see a presentation at ASCO, where you will get a sense of how well it’s working in kidney cancer, but it’s going to be a very small trial. We need a much bigger trial.

This is a more general question, and I never hear anything about it. Is anyone collecting data on your outliers, those people who survived the interleukin 2, IL, or data, anything to see if there is something homogeneous about them or any attributes? I just never hear anything about this.

DO you mean people who can’t go on trials, or people who do really great?

Those who do really great, those with long PFS or OS, people

There are people who are thinking about those questions and there are more often cases, where when people present, their tissues or blood and tumor stored for analysis so we may be able to do that kind of study in the future. There are people who are looking at genetic predictor of response to treatment but right now there are no great predictors of response to these agents. We need to do a lot more work on that. We don’t understand why there are great responders—yet. We have the capability of learning about that now we are collecting information.

I just wonder if it is lack of patients or lack of money, if there is no big drug involved.

Any research will say there is lack of money, we could also do with more money. There is also a lack of insight. If we have the information, can we tease out what it is important. I think Dr. Jonasch is going to save me with an intelligent answer.

Jonasch: I don’t know if it will be intelligent, but it is an answer! Anderson has an unusual responders program, and what is to be done, and Dr. Tannir and I are both participating in that. We are taking those with outstandingly good and outstandingly bad responses, and we are performing sequencing analysis to get clue to determine what exactly makes those people different. Hopefully I am getting my data back in the the next month or so, with individual are treated with Sunitinib. So it will give us some ideas , to understand those differences. So, no answer yet, but work underway.

I don’t want to be morbid, but want to understand. You have just said about sending tissue, is that at the end of your life or?

It’s usually at the time of diagnosis, so Anderson is great example of this. They will ask you after the tumor is removed, after Dr. Wood removes it, can we have a piece for our tissue bank? They will save it, save it in an impersonal way, and they will use samples from your body, not just the tumor, your urine or your blood, things like that and track your outcomes, along with a large number of people. By donating that tissue upfront, it is a lot more useful and we can get a lot more information about your tumor if we can get a fresh piece of tumor. We like fresh tumor. We’ll take anything, but fresh is better.

I am asking a question which may have explained a bit earlier,how the patient is handling side effects and how that puts a greater responsibility on the patient. How is a patient who is not able to come to a place like MD Anderson or these other center. How is a patient able to help guide or cooperate with his local oncologist and handle this massive amount of information and differentiate whether he is getting the best treatment possible.

OK, that is a complicated question, For the most part, now that we are 5-6 years into these new agents, most oncologists are making good treatment decisions. In the case where you are not sure, you’re unsure, you can always ask, “Can I get another opinion?” I think most oncologists don’t feel awkward about that. “Is there someone you can call to ask about my side effects? Is there someone you might send me to for this next treatment decision? These days, the good news is that you can end up receiving a lot of your treatment close to home, since these drugs are approved, but getting a confirmation is sometimes helpful, just for piece of mind. Most oncologists that I work with are pretty comfortable making that referral. Going through your doctor is a lot more productive than going around. That’s my personal experience. They get experience, they work in tandem, which is better than losing track of the local person.

QED