So we could predict who was going to respond in the primary tumor, so the question was, “Can we use that as some sort of bio-marker?”

PART Two of Several Parts;

“Cytoreductive Surgery for Metastatic RCC: It’s Not for Everyone”

Dr. Christopher Wood

Integration of Surgery and Systemic Therapy in the Treatment of Kidney Cancer

Also referred to in the KCA program as “Role of Cytoreductive Surgery in the Treatment of Metastatic RCC

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

April 14, 2012; KCA National Patient Conference

Cytoreductive Surgery for Metastatic RCC: It’s Not for Everyone

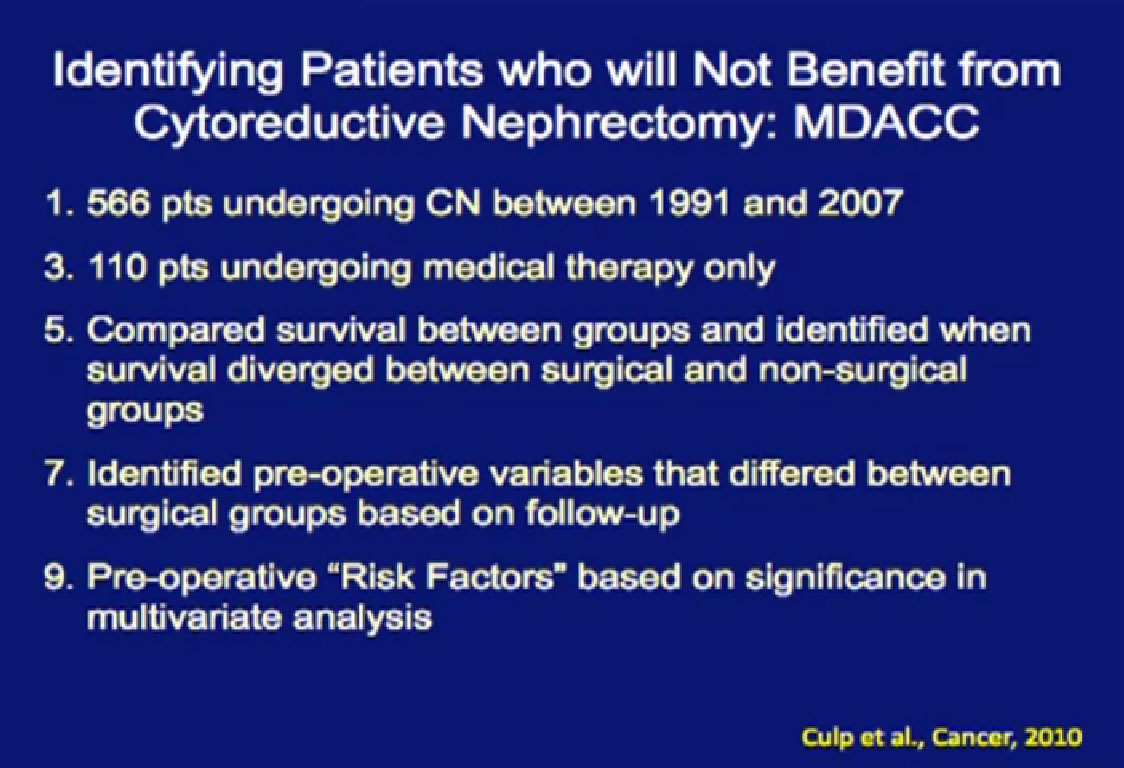

Identifying Patients Who Will Not Benefit from Cytoreductive Nephrectomy

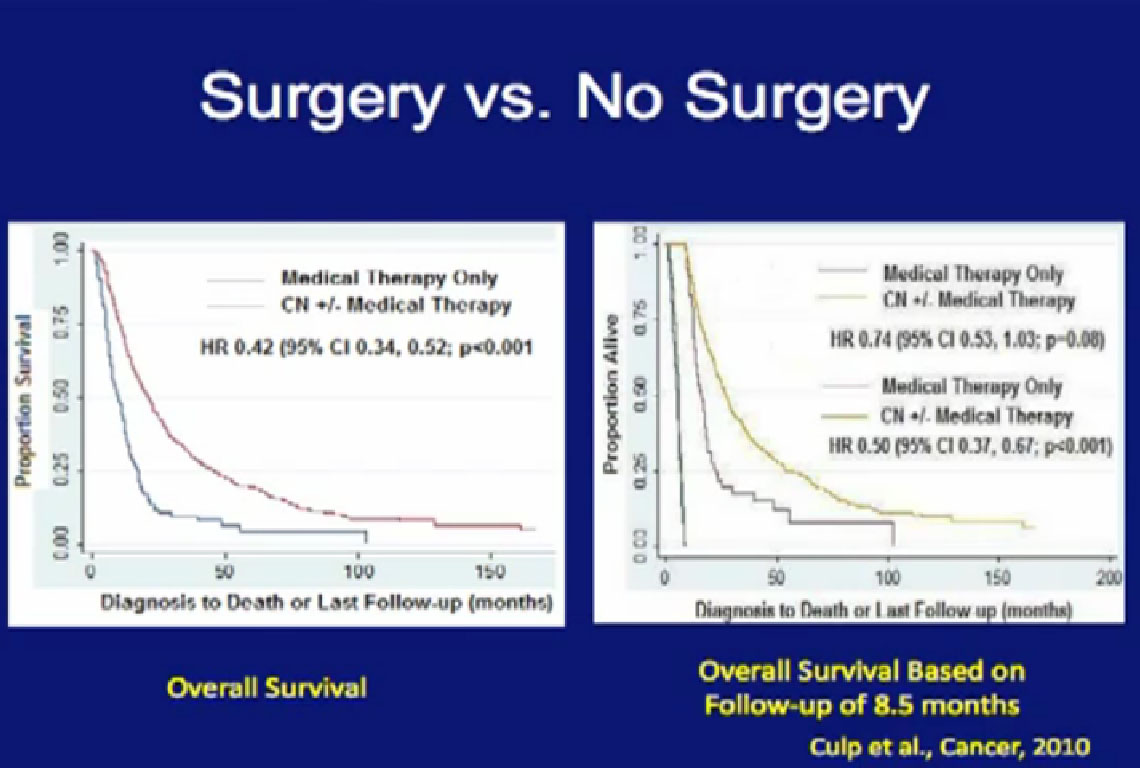

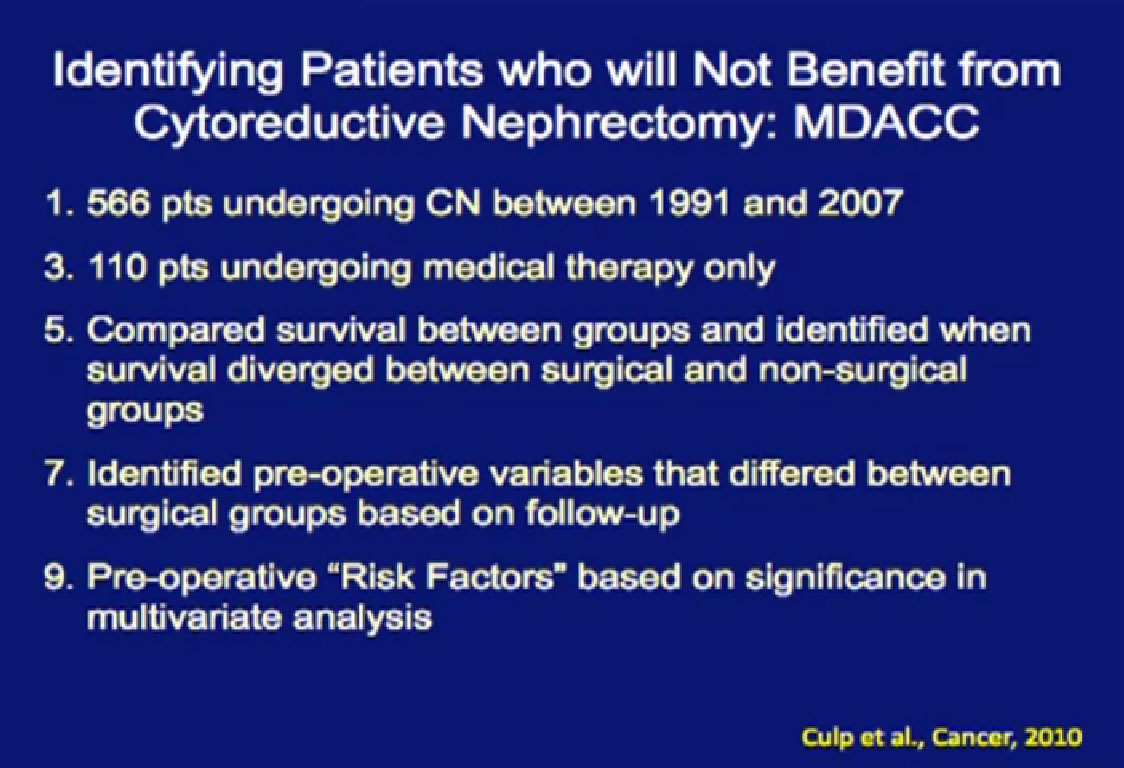

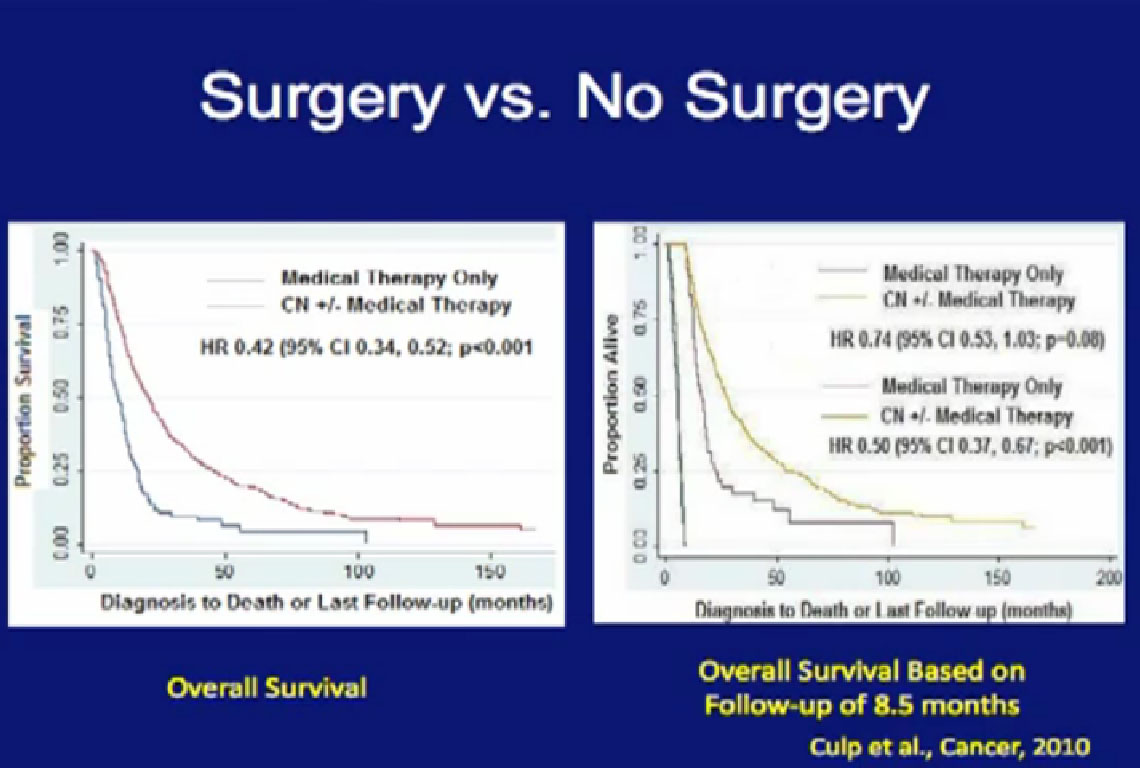

Cytoreductive surgery is not for everyone. Certain patients will not benefit from surgery. We (MD Anderson) did a study to see if we could accurately select those patients who would not benefit from such a surgery, to save them from a surgery likely to be highly morbid and not beneficial. We compared 566 patients undergoing surgery to a group of 110 patients were treated with their tumors in place and treated with medical therapy only.

We tried to predict for which (patient) factors predicted outcome. We at MD Anderson can be very aggressive in our surgeries as we believe in cytoreductive surgery, so these patients who could not have surgery were probably the worst of the worst. For these patients, treated with medical therapy only, the median survival was only 8.5 months.

With that in mind, we looked at those patients who underwent surgery. If those patients did not live beyond 8.5 months after surgery, they probably did not benefit from that surgery. What factors predicted for those patients to live longer than the 8.5 months than did the medical therapy alone group?

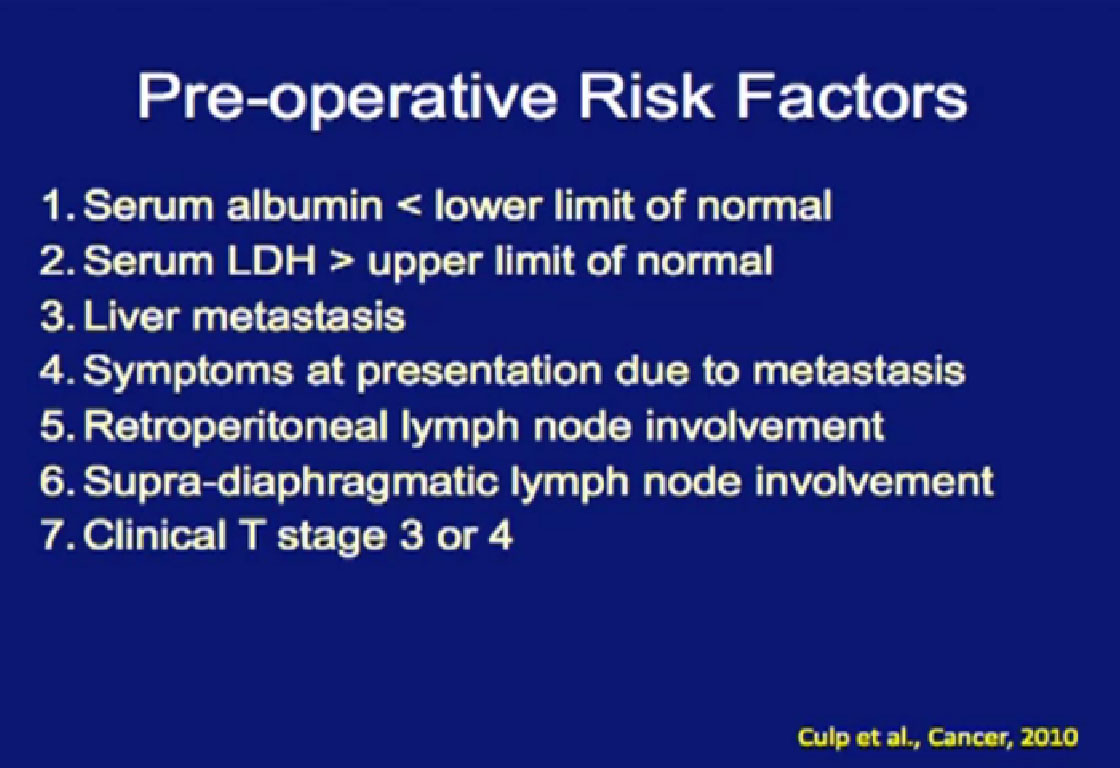

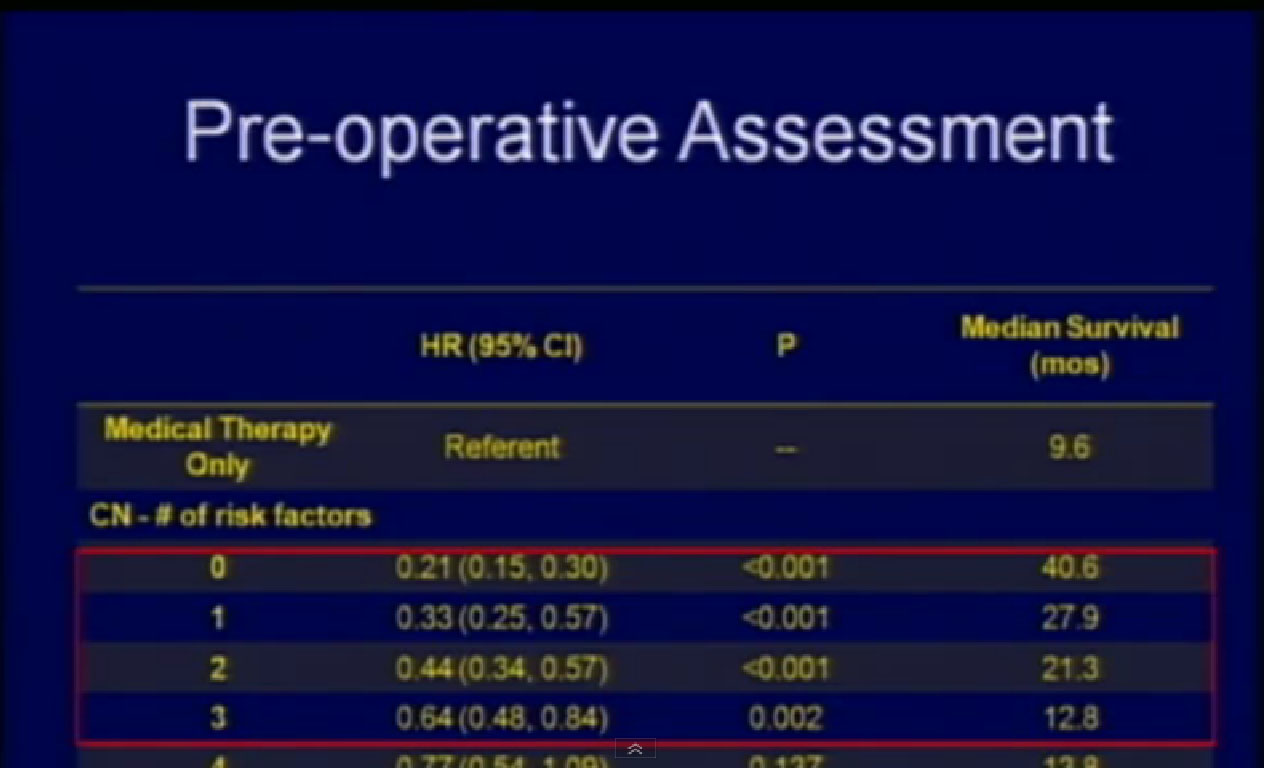

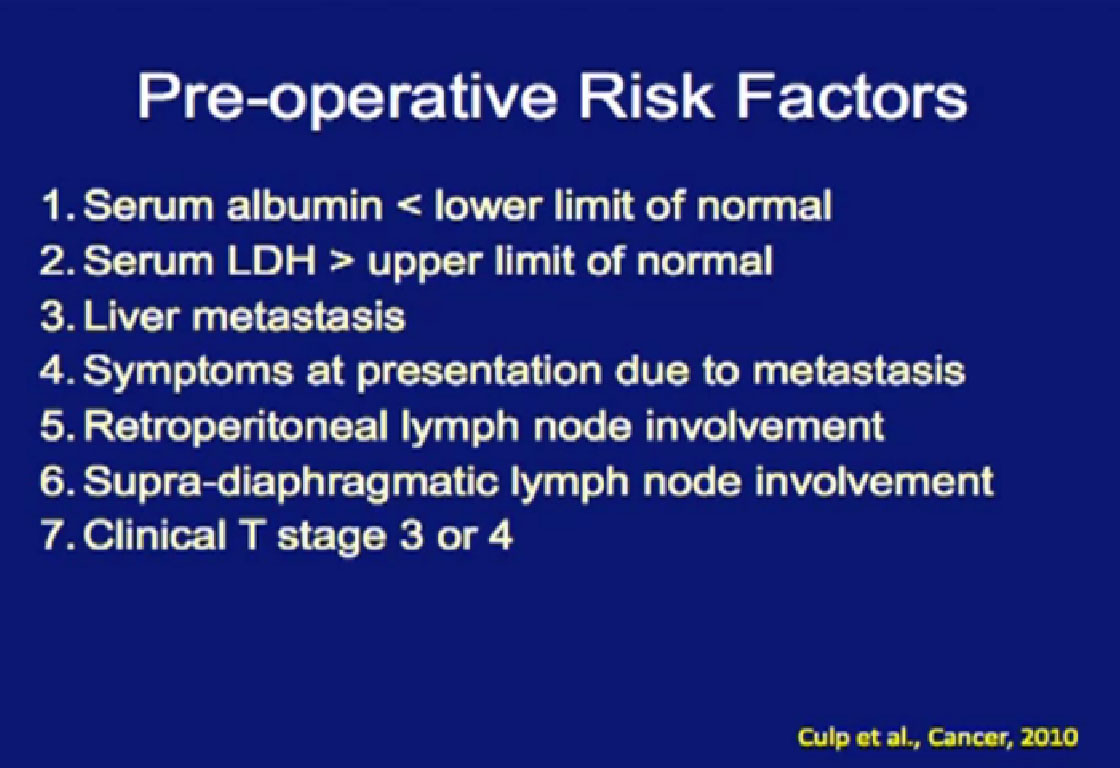

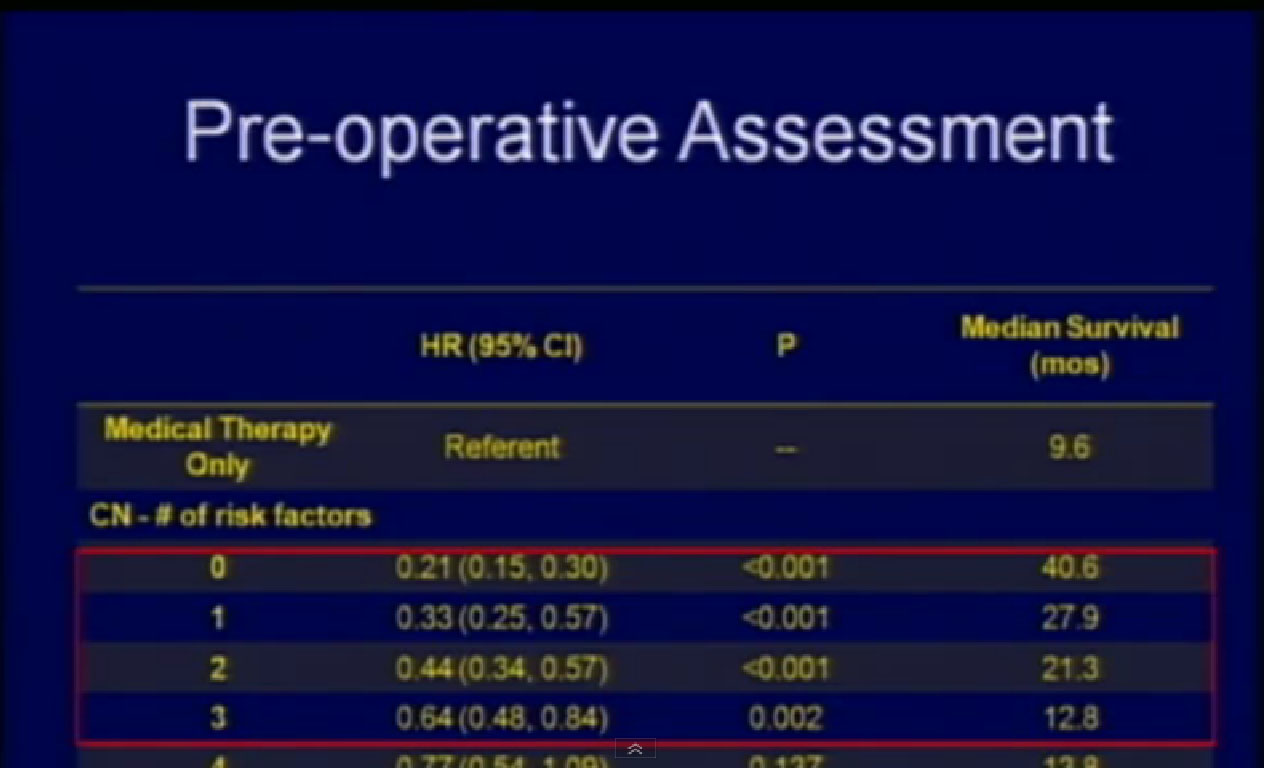

What factors would be predictive of how one would do? We identified the above factors; low serum albumin, an overall nutritional status lab value, elevated LDH, also a blood test, the presence of liver mets, presence of symptoms due to those metastases, retroperitoneal lymph node involvement, (discussed earlier as a bad sign),supra-diaphragmatic lymph nodes and locally advanced T state. All of these features predicted for a worse outcome.

If a surgical patient had three or fewer of those features, he did significantly better than those who received medical therapy alone. But if a surgical patient had more than three of these features, that outcome was the same or worse than those who received medical therapy alone. So now we are using these features to prospectively select patients for surgery.

Can We Do Better?

Is the relevant question whether or not surgery should be incorporated into the management of metastatic kidney cancer?

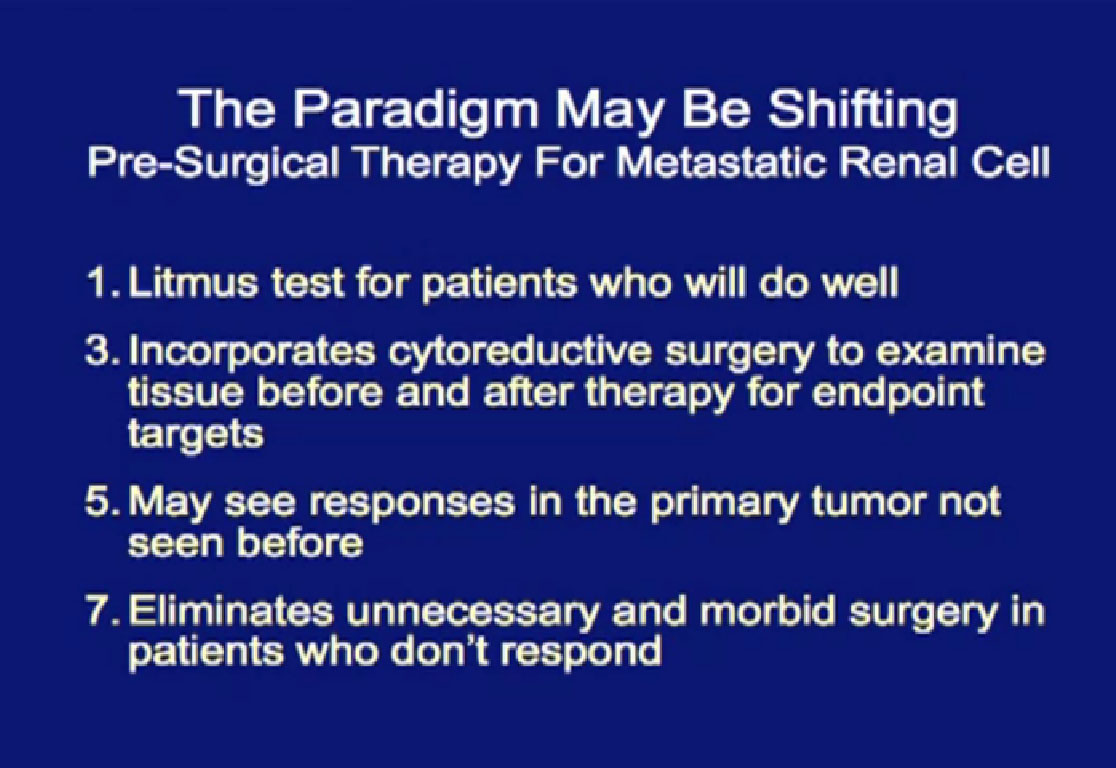

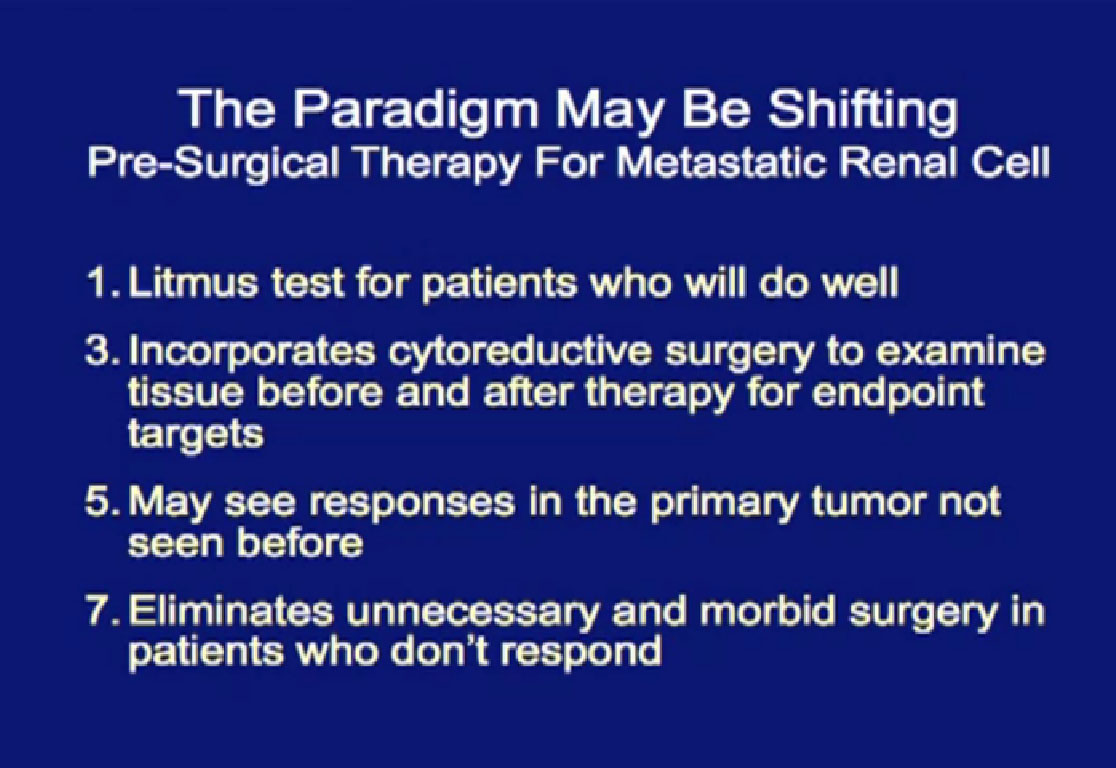

I argue the more relevant question is whether there is a role for “pre-surgical therapy” for metastatic kidney cancer.

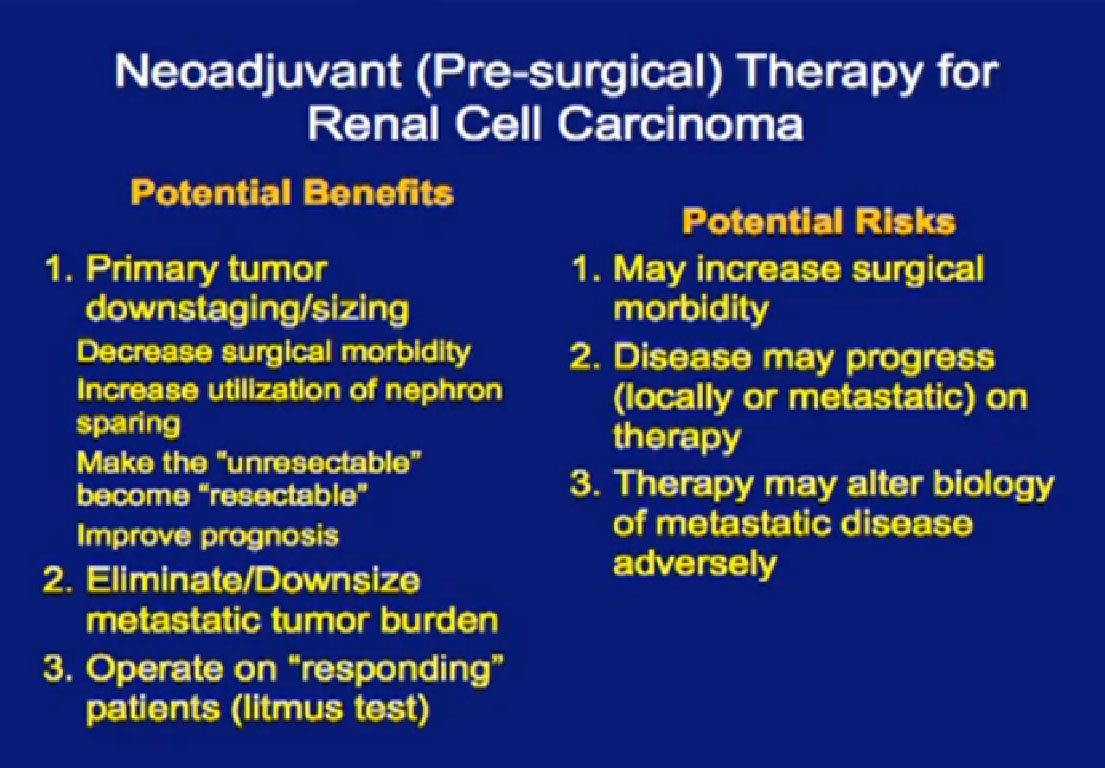

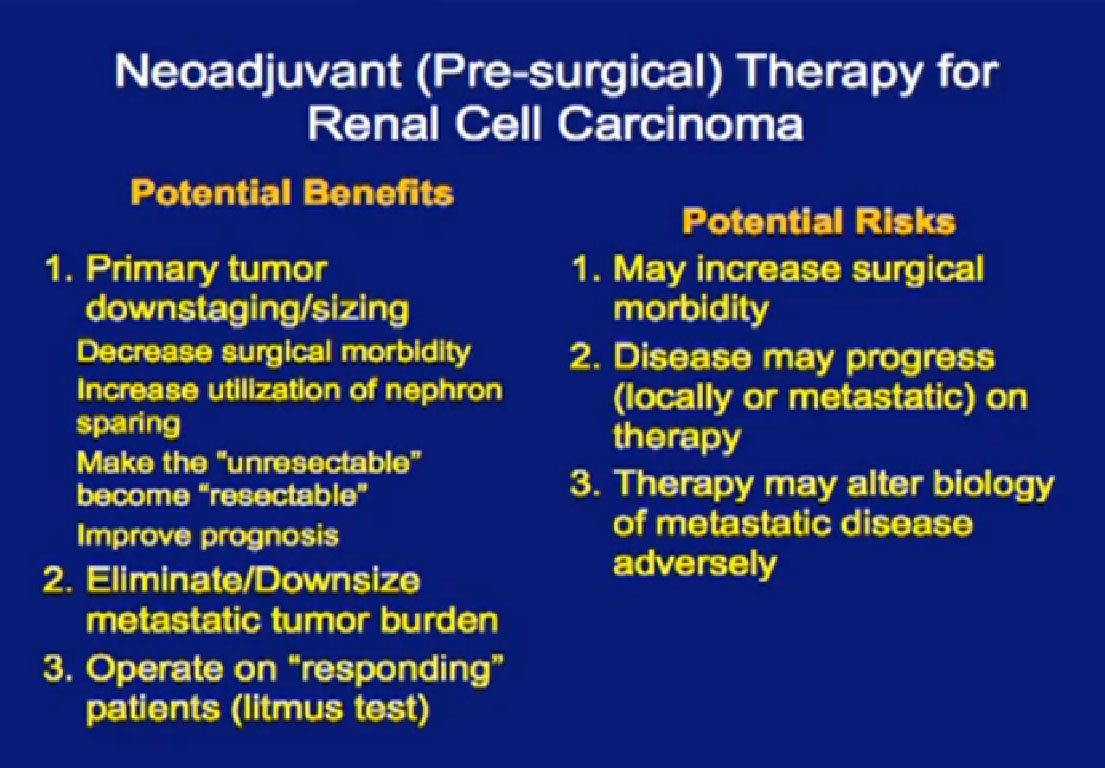

Pre-surgical therapy means to give some targeted therapy for some defined period of time, then go to surgery and resume targeted therapy after surgery. The potential benefit may be to use the pre-therapy as a selection process: patients who do well are those taken to surgery, and the ones not doing well are spared a surgery that not likely to give them benefit. It allows us to harvest (surgical) tissue that has been treated with these agents. With that available, we can study it to see how targeted therapy affects the tumor, what pathways are turned on and off, to help generate the next treatments. It may shrink the primary tumor and make the surgery easier, most important this is that it allows us to spare patients from surgery that they are not likely to benefit from.

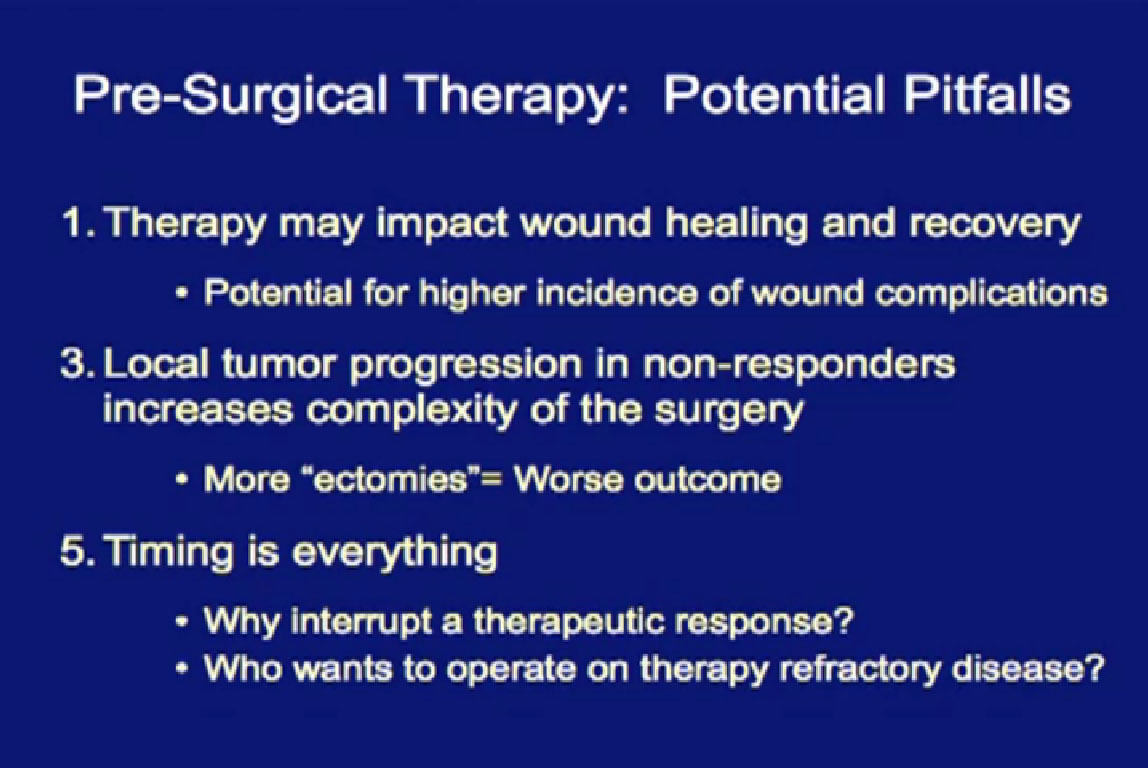

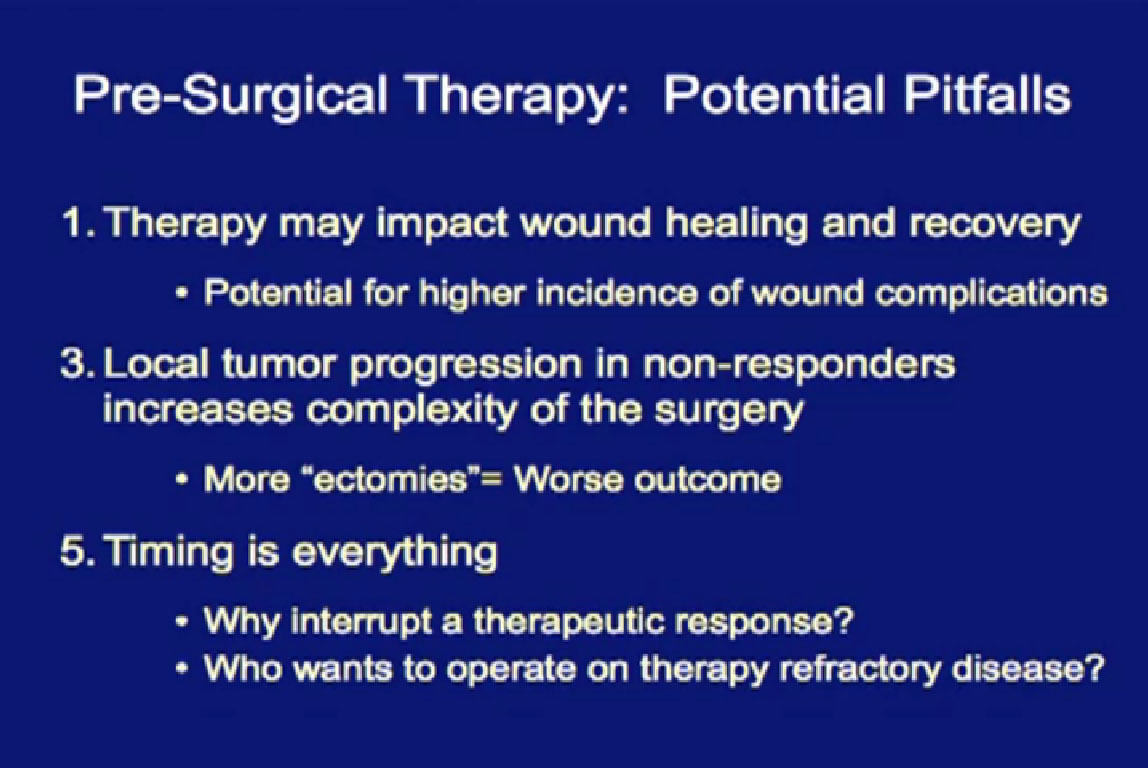

However, targeted therapies don’t just target the tumor. They also target wound healing, which is why many patients who get this therapy have wound complications. The tumor will not respond to the therapy and may grow; a patient who was a surgical candidate all of a sudden becomes not a candidate for surgery, because the tumor has grown. He may need a more extensive surgery. The more I take out, the more difficult it is for you. And timing is everything. If you get targeted therapy and respond well, why stop that to send you to surgery? And as a surgeon, if you are not responding to targeted therapy, why would I want to take you to surgery?

Potential benefits are that the primary tumor may shrink, may downstage or downsize, and make surgery easier. Maybe we could do partial nephrectomies on everybody, save some kidneys. It may make the unresectable become resectable. It may improve prognosis. In patients without metastatic disease, it may eliminate micro-metastatic disease. (Pre-surgical targeted) therapy might be used as a litmus test of response, but there are risks, including surgical morbidity and lack of response. Plus there is pre-clinical data which suggests that in some cases, targeted therapy, treated in this fashion, may make the biology of the disease worse.

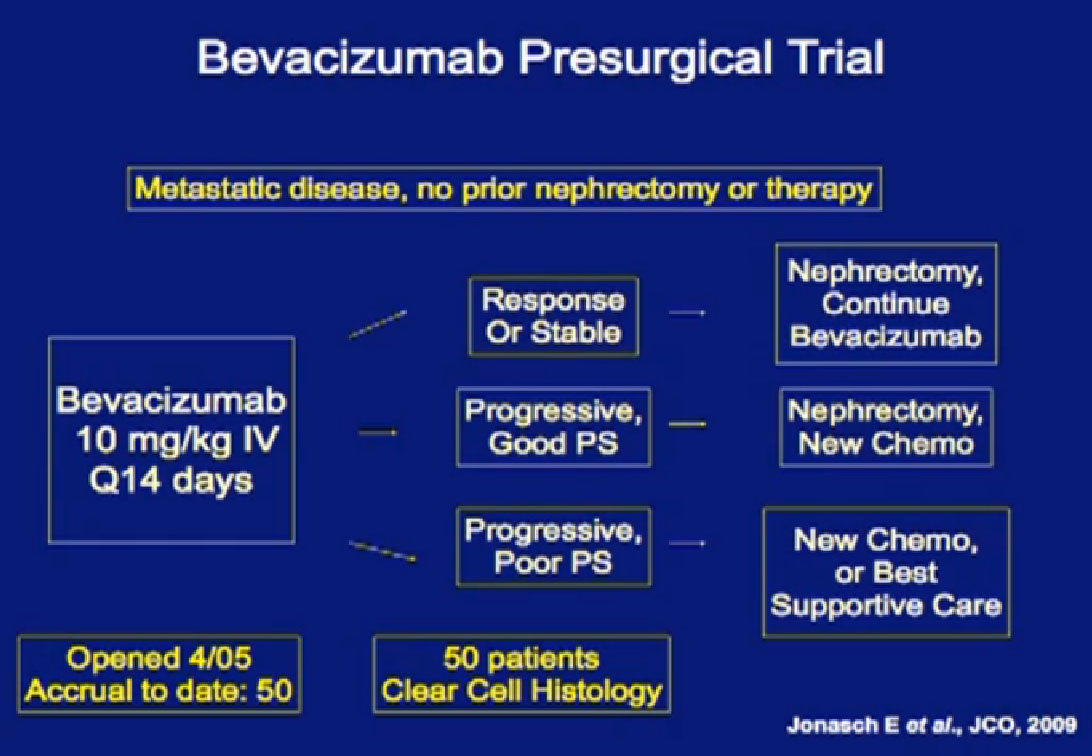

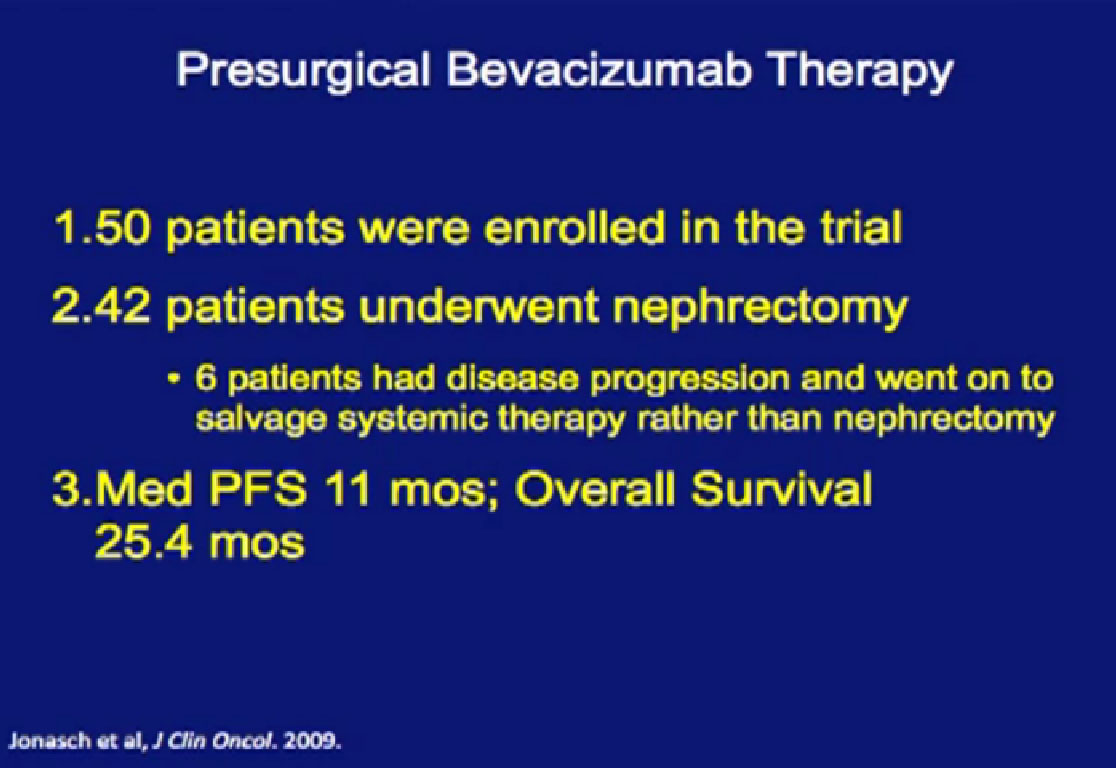

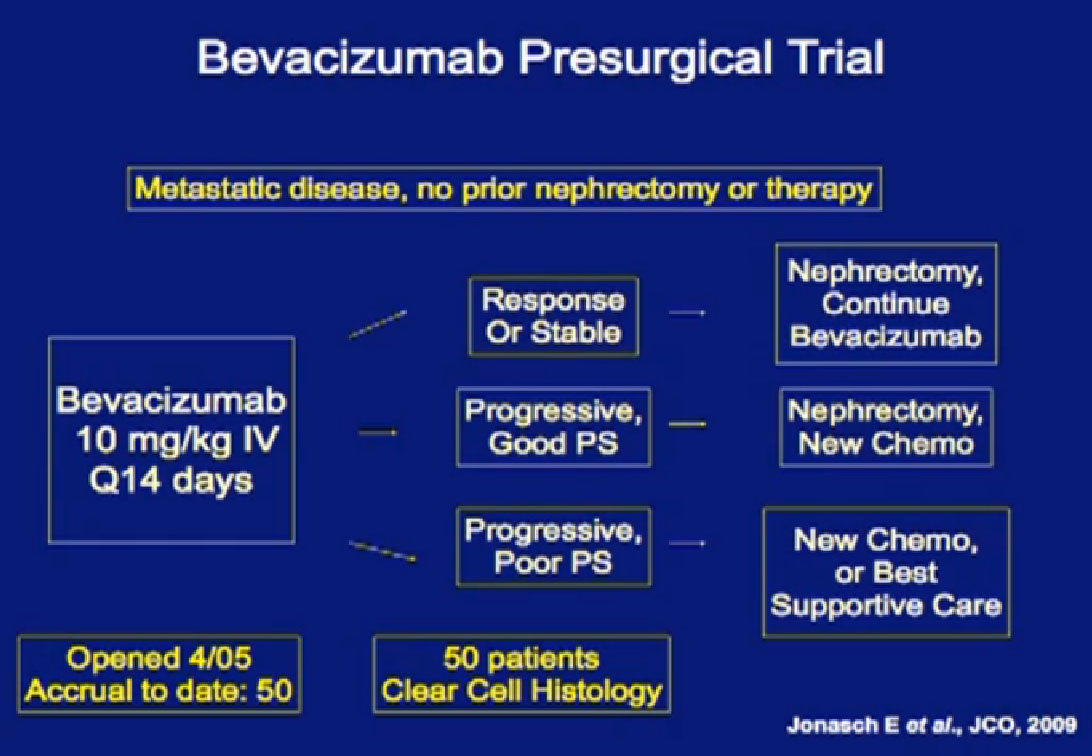

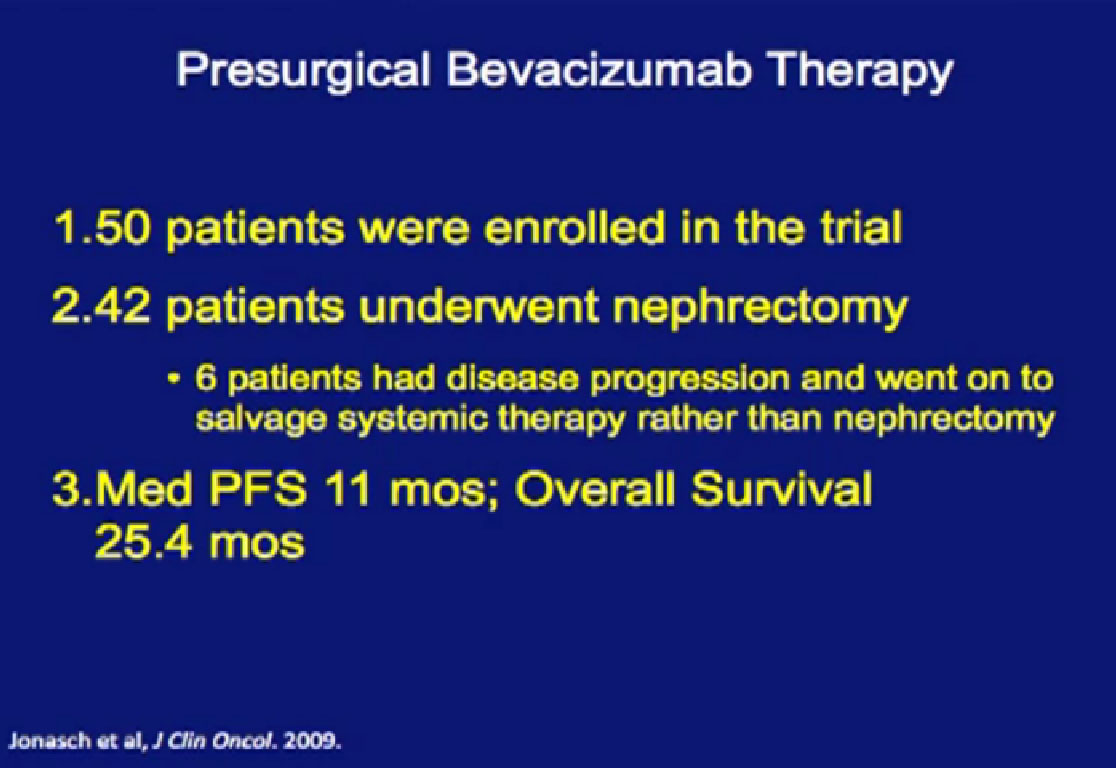

This is the MD Anderson trial with Bevacizumab (Avastin), where patients were treated with Bevacizumab for two courses of treatment and then went on to surgery and back on Bevacizumab after surgery.

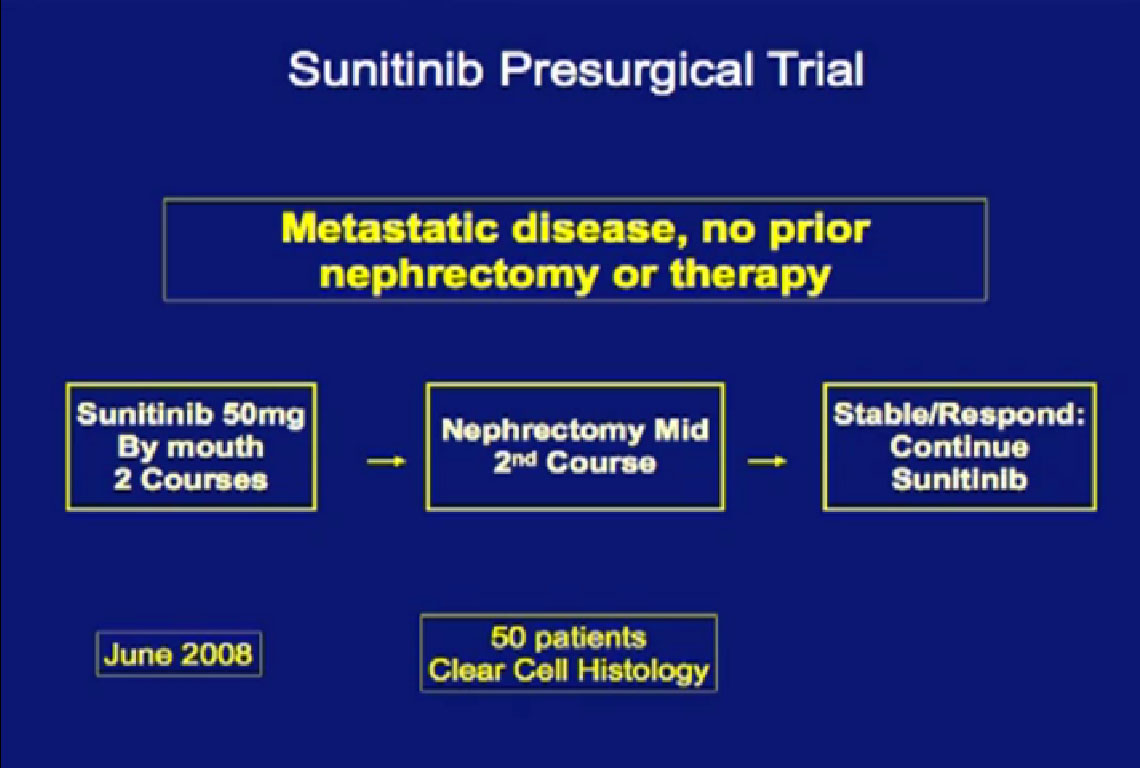

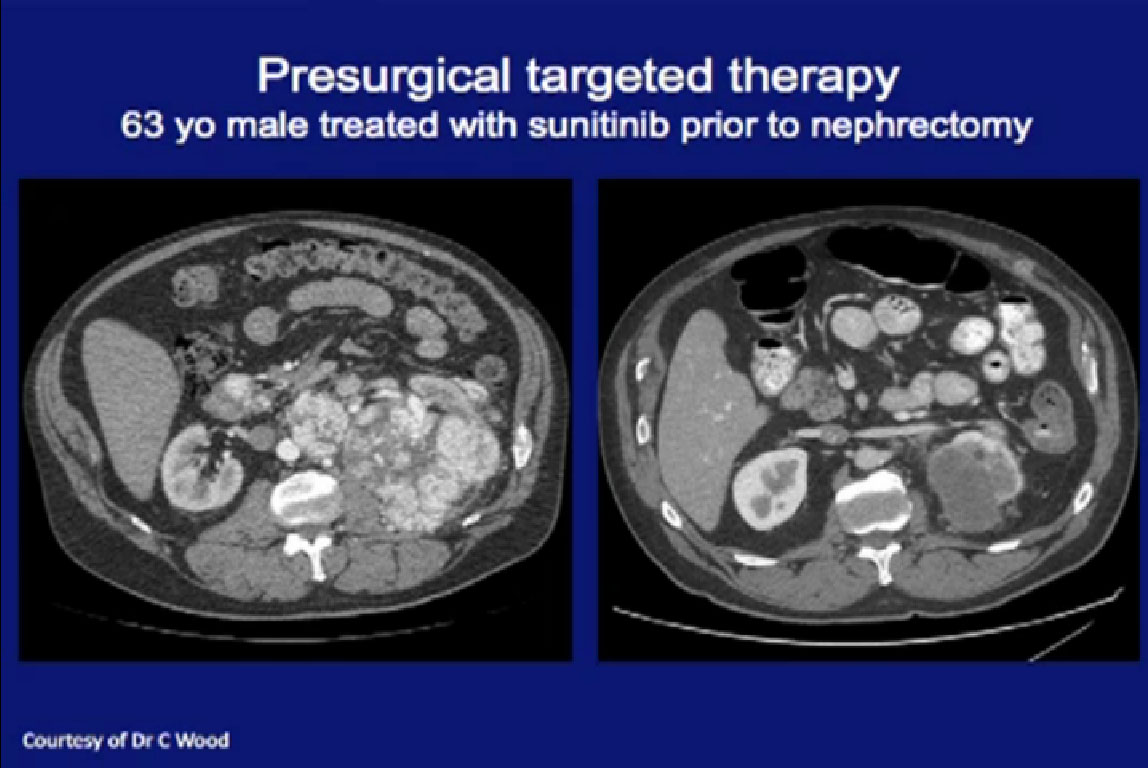

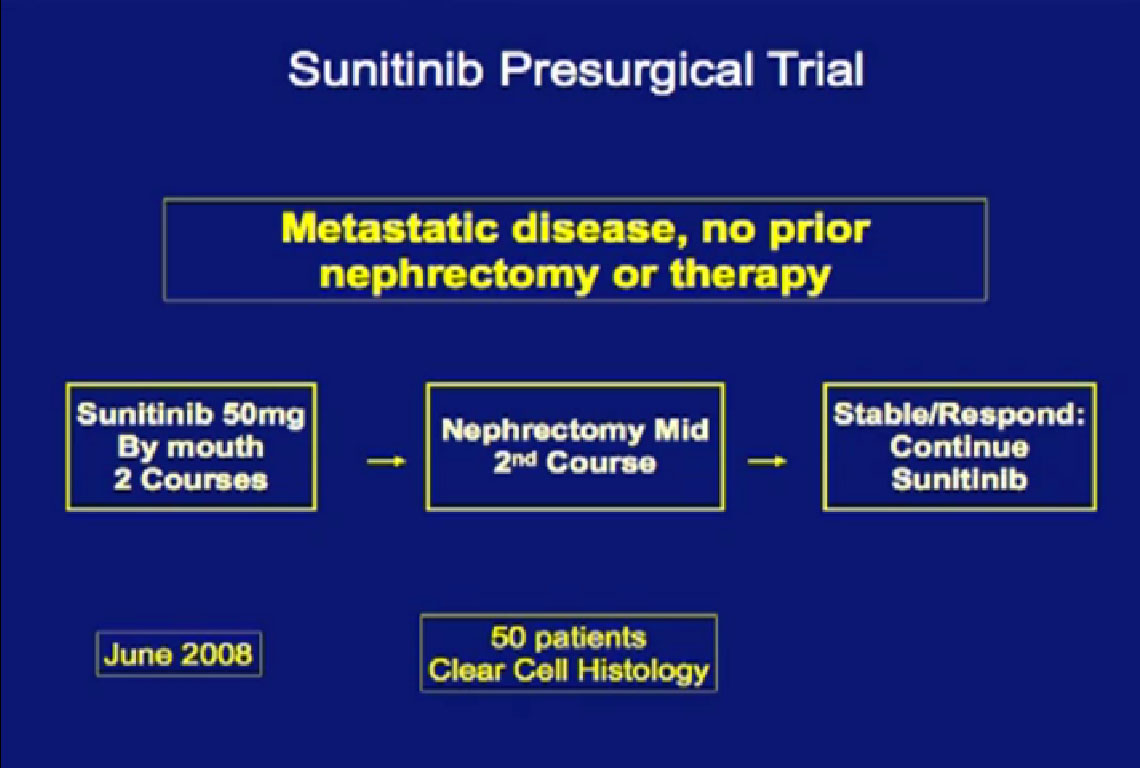

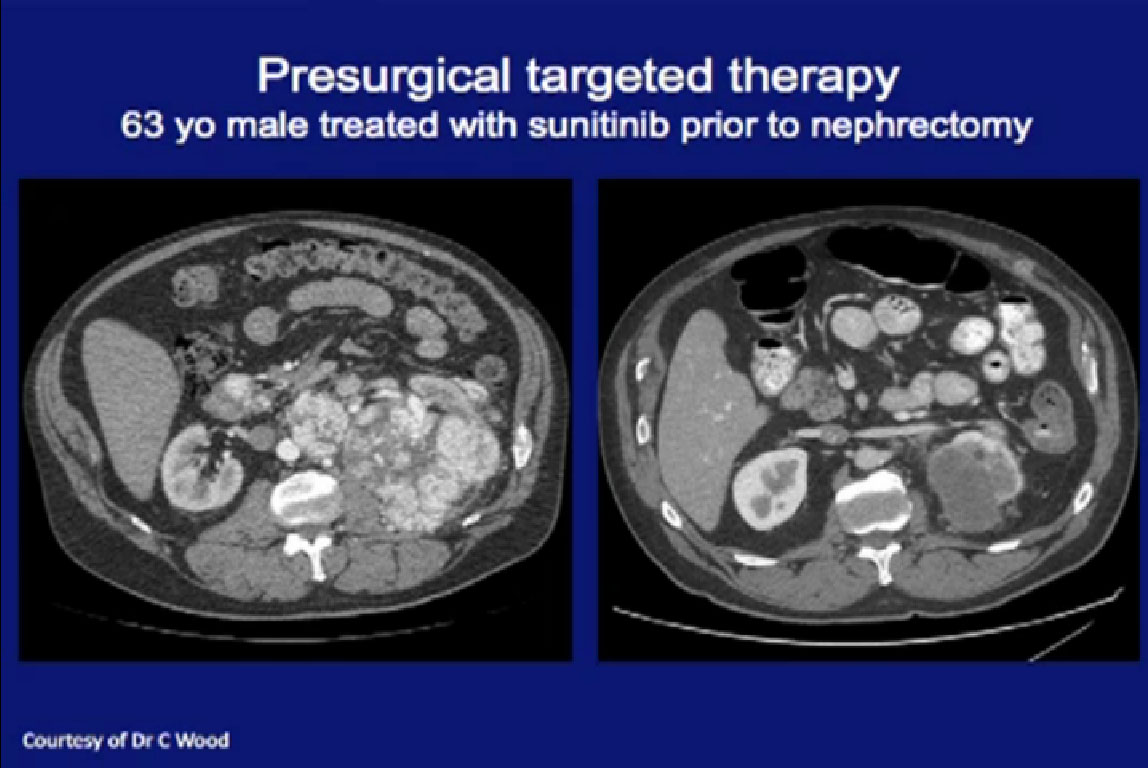

We recently completed this Sunitinib trial. Patients completed two courses of Sunitinib, followed by nephrectomy and went on to receive Sunitinib post operatively when they had a response.

We recently completed this Sunitinib trial. Patients completed two courses of Sunitinib, followed by nephrectomy and went on to receive Sunitinib post operatively when they had a response.

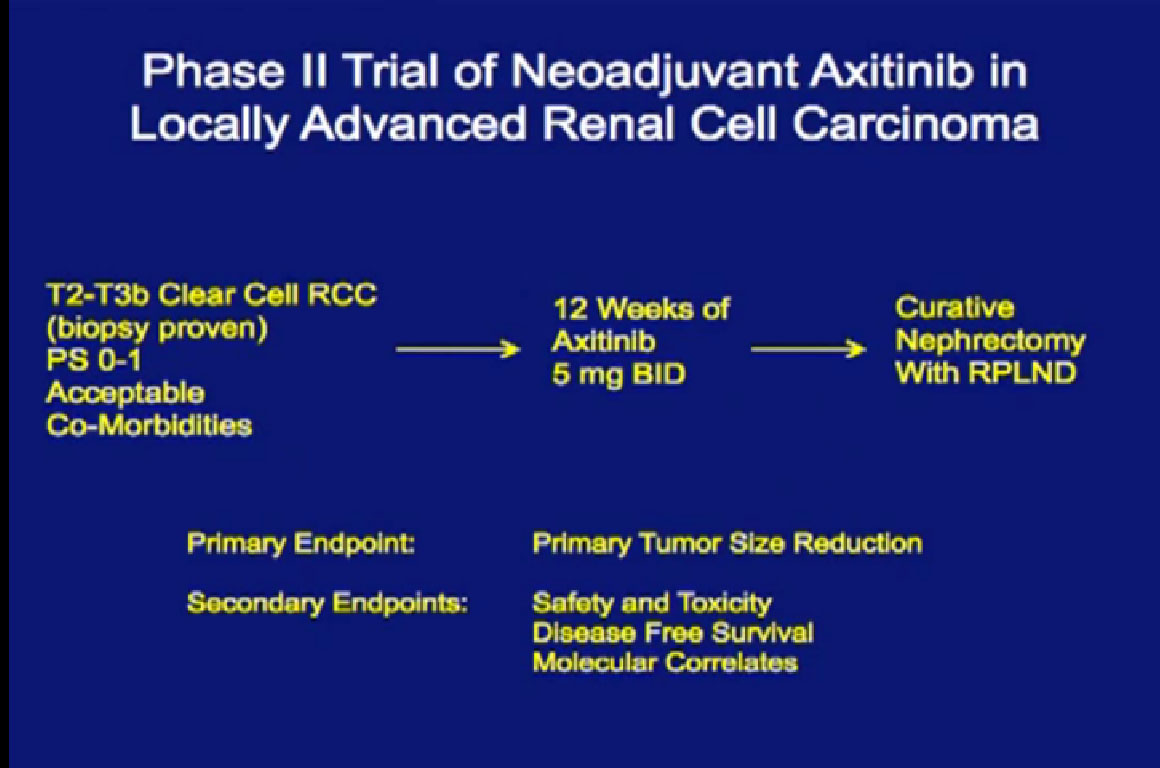

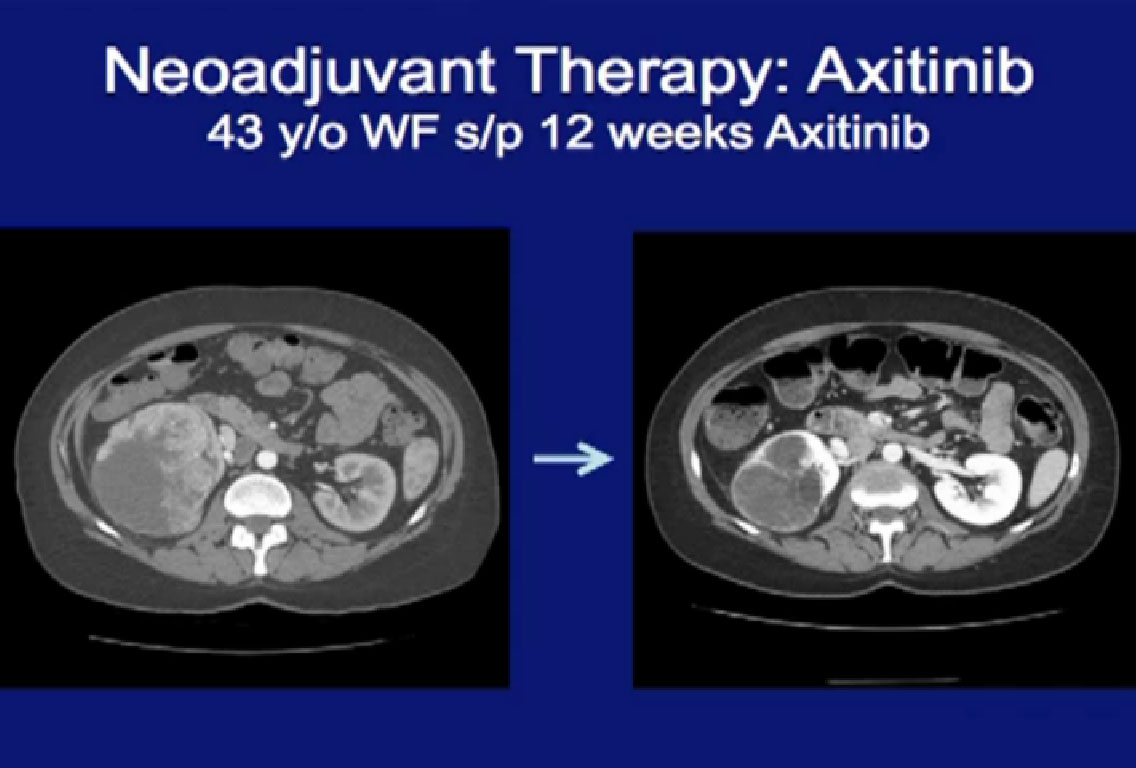

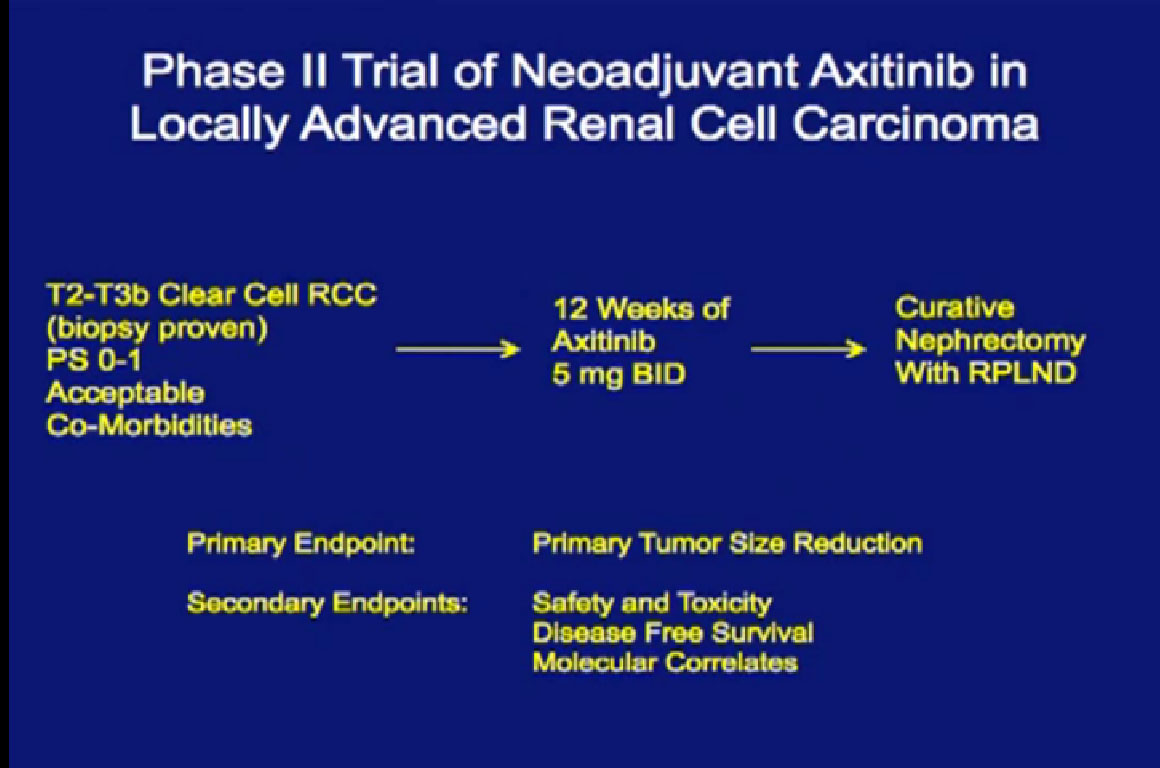

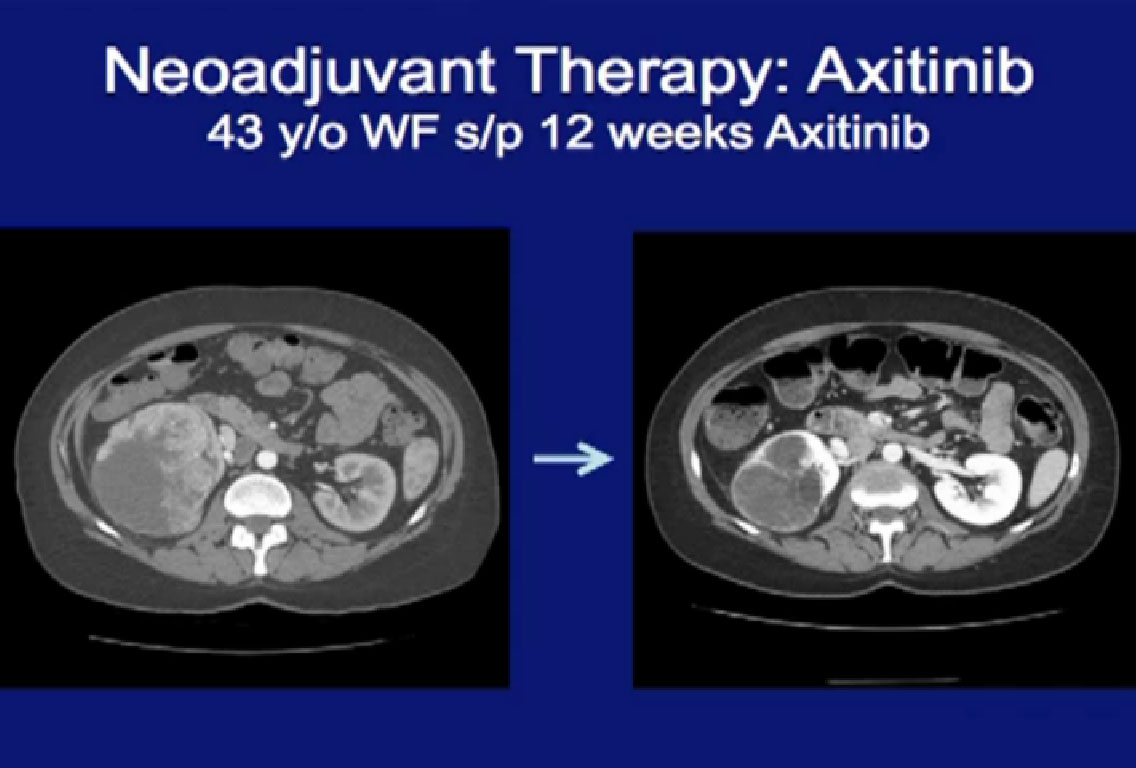

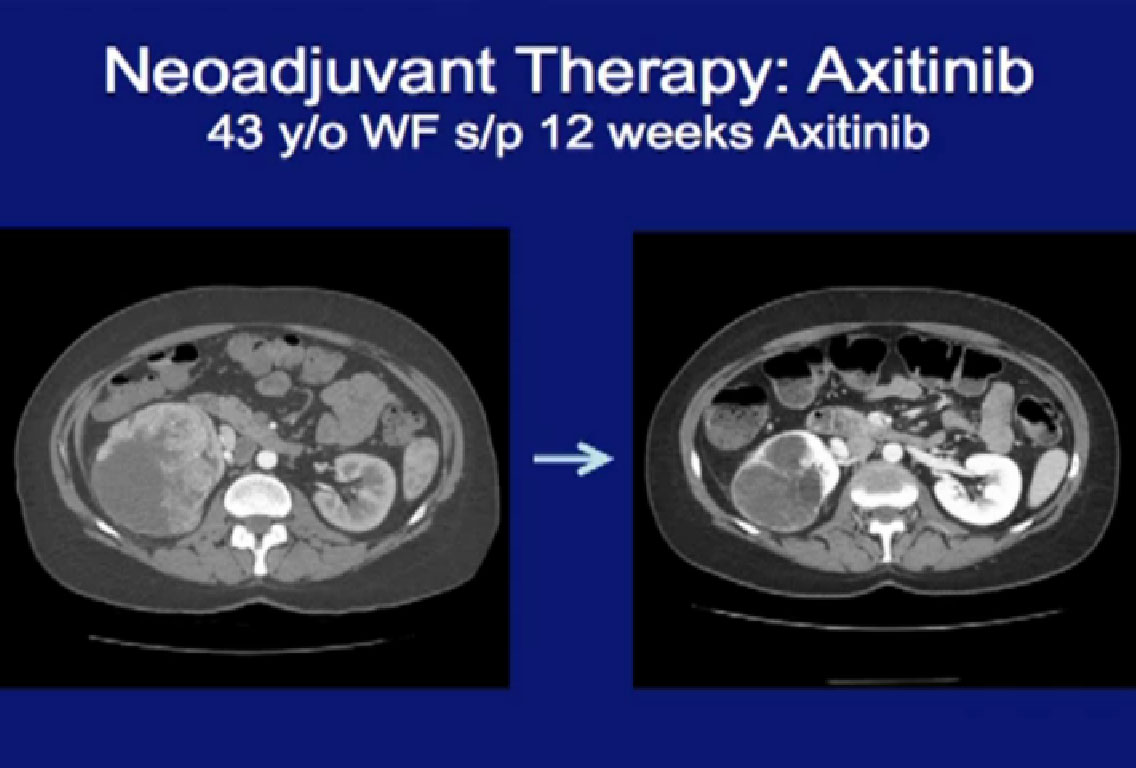

This is my Axitinib trial, where patients with locally advanced disease would receive three months of Axitinib, and go on to get a curative nephrectomy

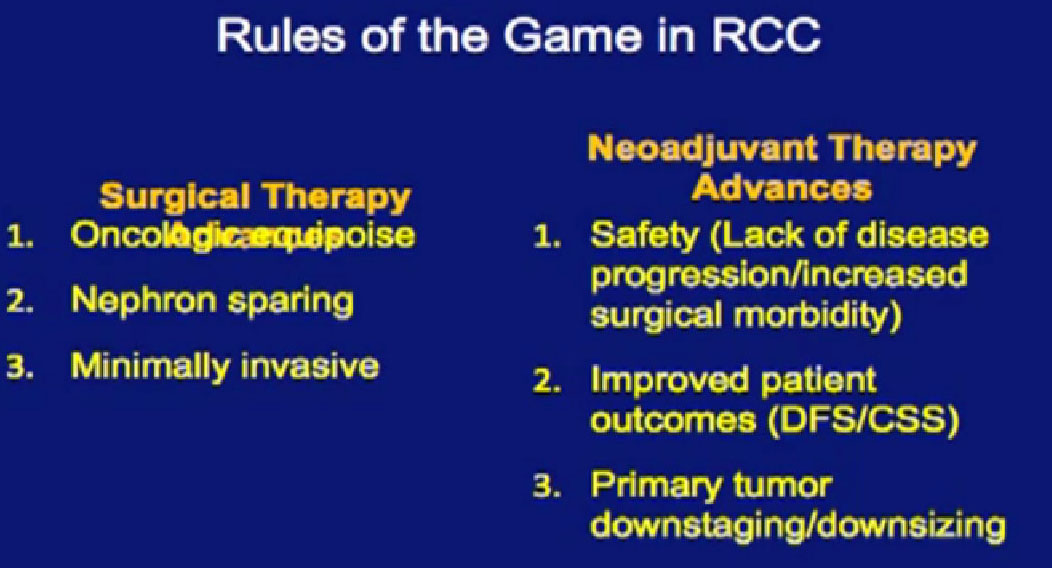

Dr. Kamar showed you earlier an evolution in surgery over time. Ten years ago, everyone got an open nephrectomy; it was done open and very morbid. Then people began to use a partial nephrectomy and then a laparoscopic nephrectomy.

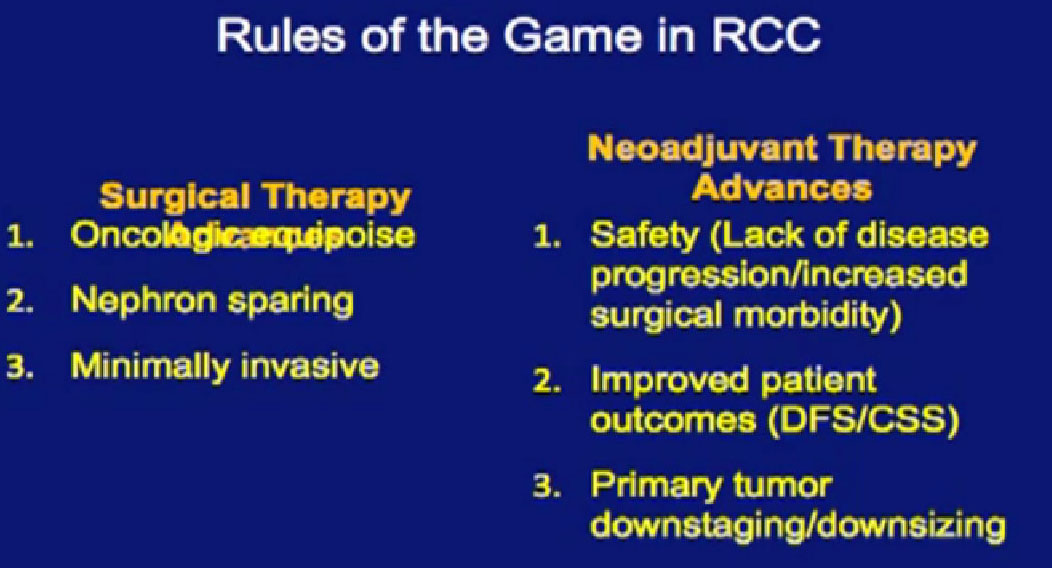

Each advance had to prove it was equivalent to the existing technique doing then and each had to show oncologic equipoise, i.e., equivalent cancer control. To give equivalent cancer control was the most important hurdle for each advance in order to be accepted. It also had to spare nephrons, for me, that the least important thing was this it was minimally invasive. Between a minimally invasive operation that doesn’t work, and a maximally invasive operation that does work, which one would you choose?

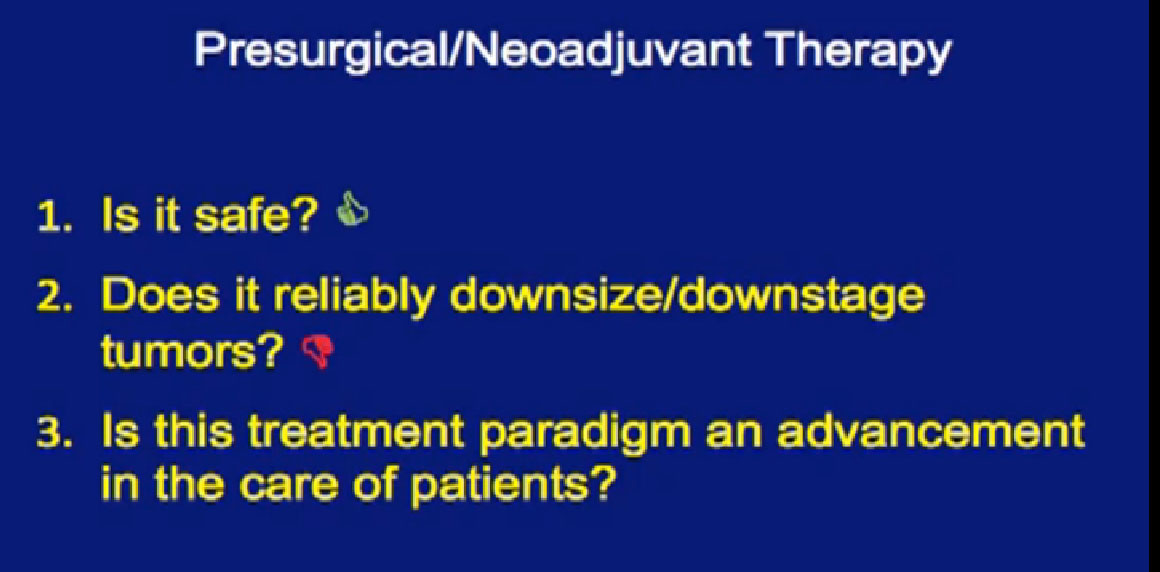

Similarly this neoadjuvant approach has hurdles. It must be safe and it must have improved outcomes. The least important is that it downsize or downstage the tumor. It is the rare patient who presents that you can’t resect. It would be nice if the tumor shrank, but that is the least important, I think.

Is NeoAdjuvant Therapy Safe?

Is neoadjuvant therapy safe? This patient (on the left) went on Sunitinib, had surgery and went on to get Sunitinib after surgery. What I did not know as the surgeon, that the patient started Sunitinib two weeks after surgery. And he had complete abdominal wall dehiscence (opening of the wound). That is his greater omentum sitting on his abdominal wall. The patient did not even realize that he had a problem and went to the MRI for his repeat staging study. He had no idea that he had a problem, so went he came to clinic and we saw that we went, “Oh, my God!”

Referencing another slide not shown here: On the right is a patient on the bevacizumab trial who had abdominal wall dehiscence, four months out from surgery. That is her small bowel (referencing upper portion of CT scan) and you can actually see it on the abdominal wall.

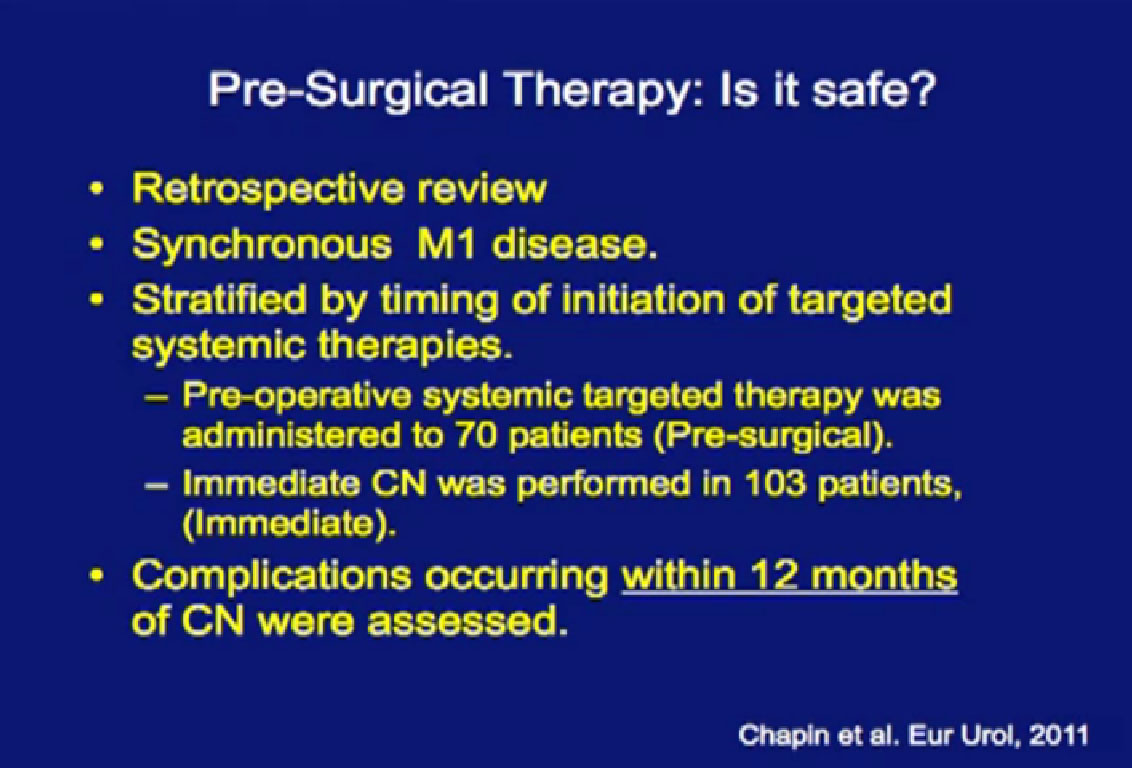

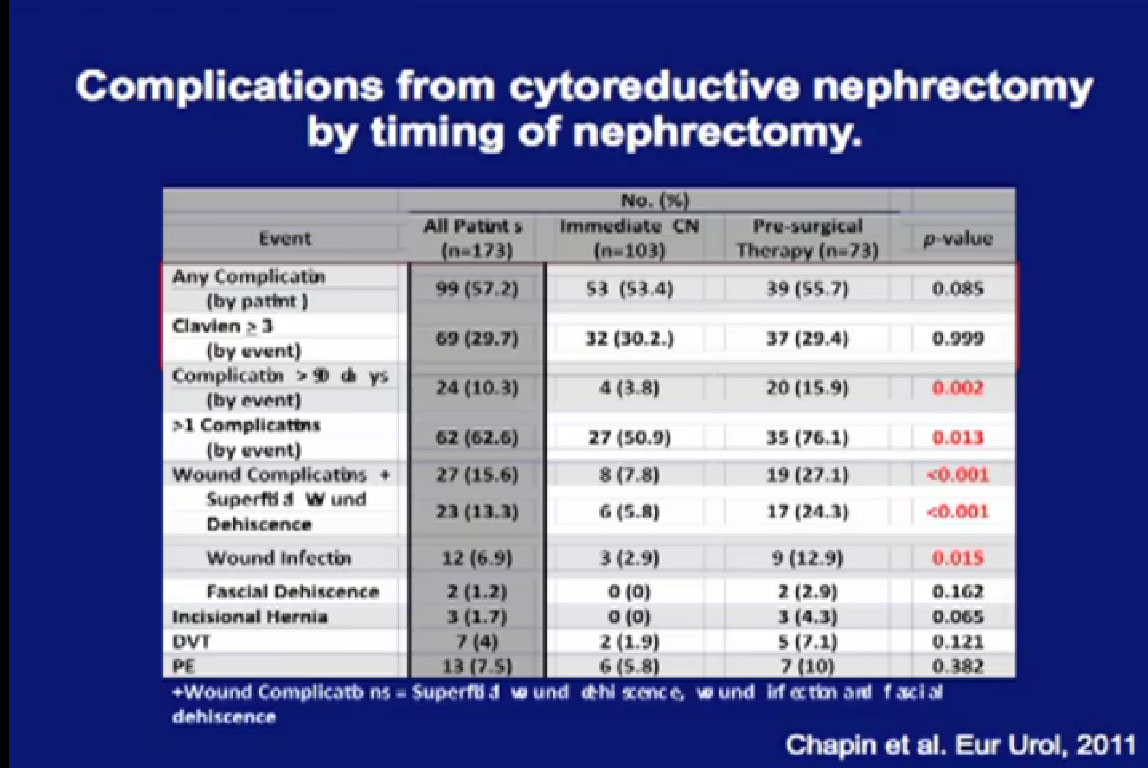

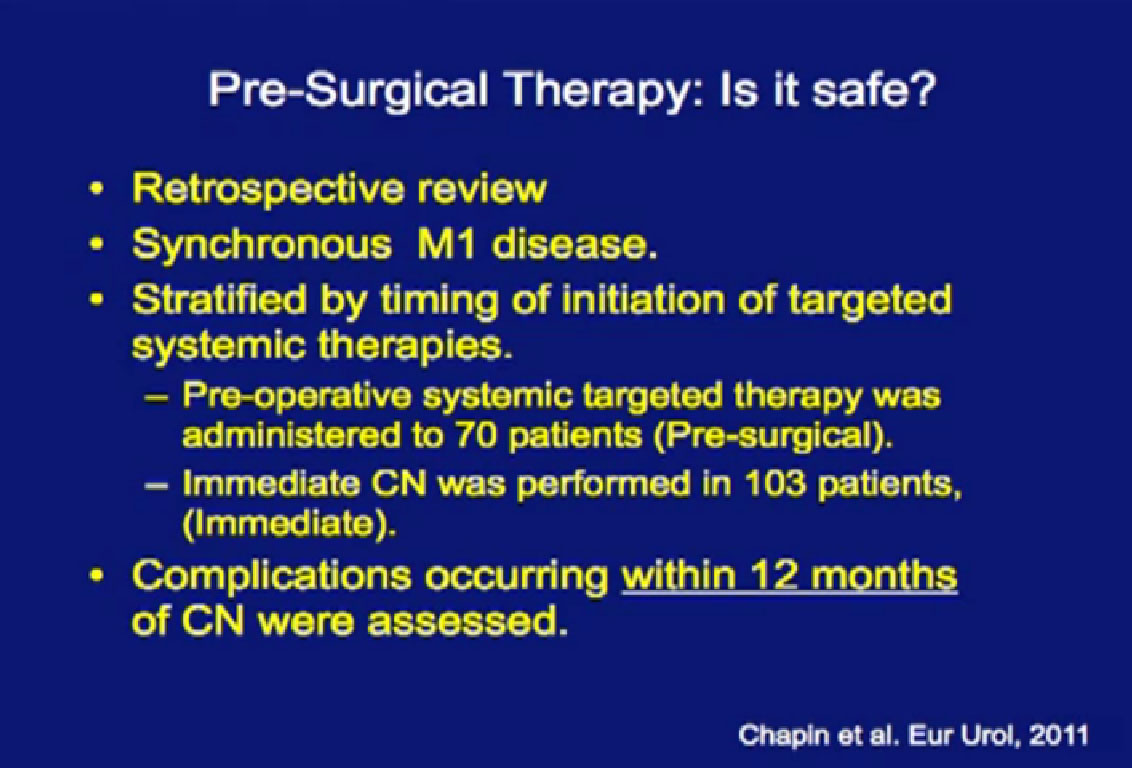

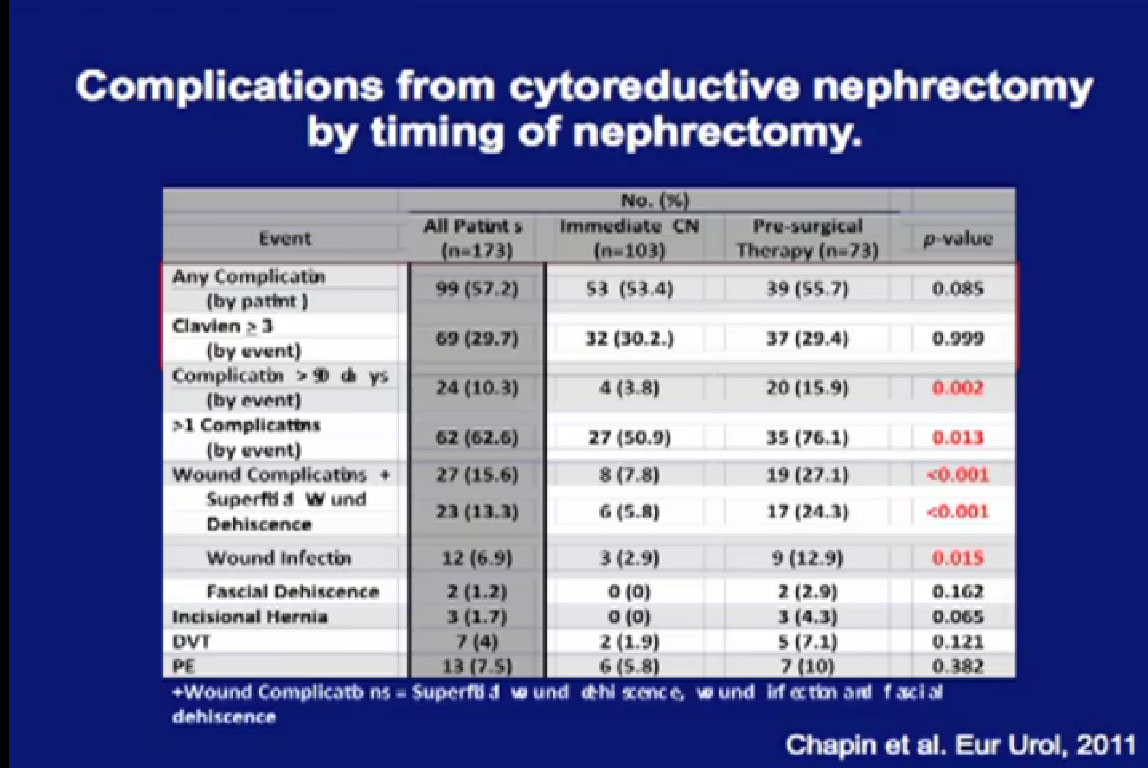

“Is this safe?” We did a retrospective study on 70 patients using pre-surgical therapy and compared them to 103 patients who had upfront cytoreductive surgery, and we looked at complications over 12 months.

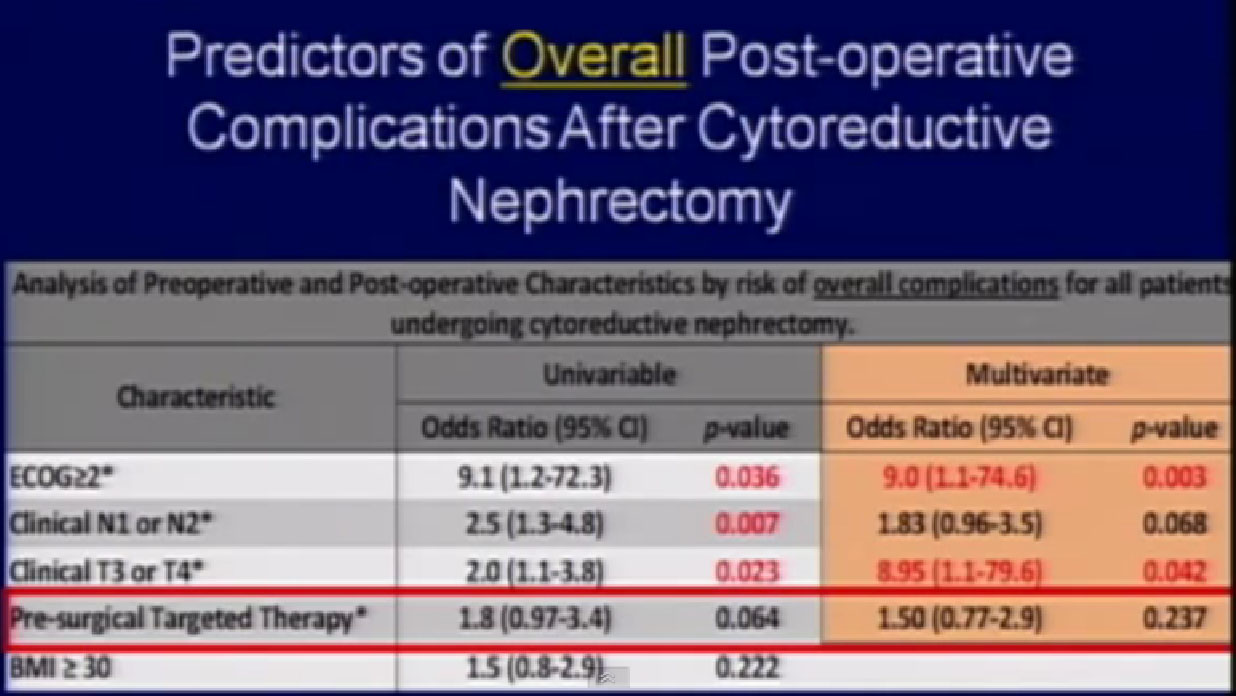

Patients who had pre-surgery treatment did not have more complications than those who had upfront surgery, nor were there more severe complications. However, they were more likely to have late complications, and to have more than one complication if they had a complication. They were more likely to have wound complications, related to the targeted therapy and wound healing.

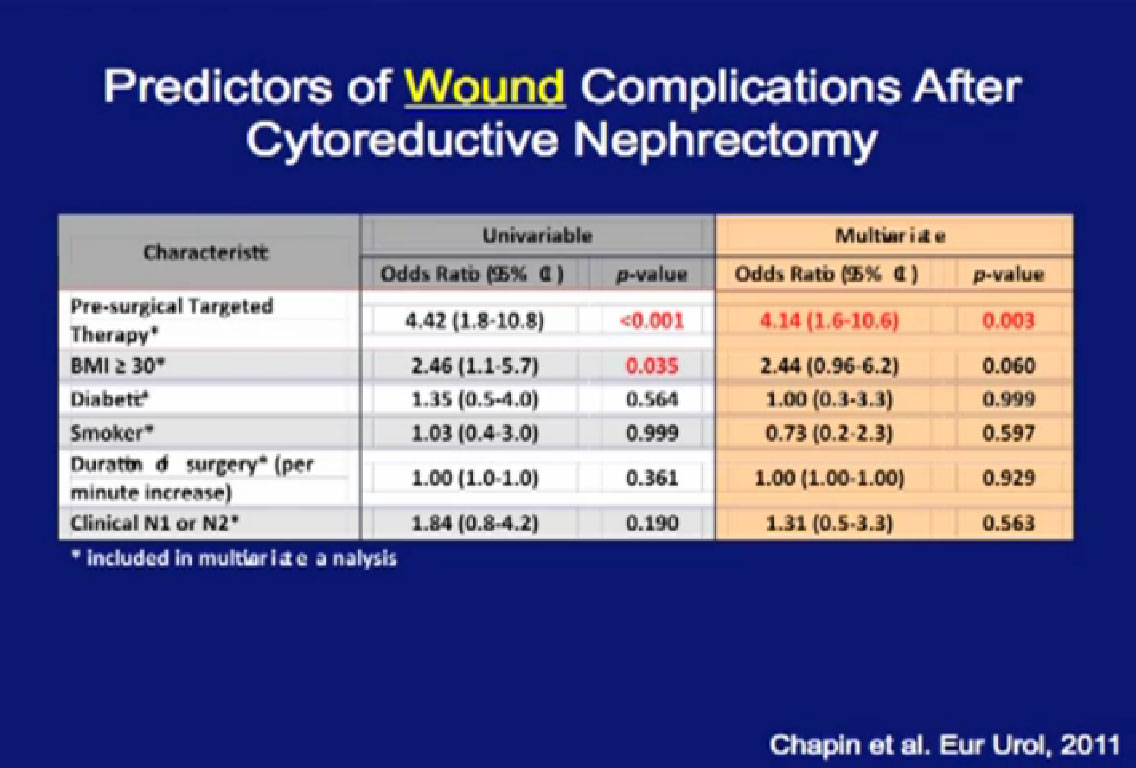

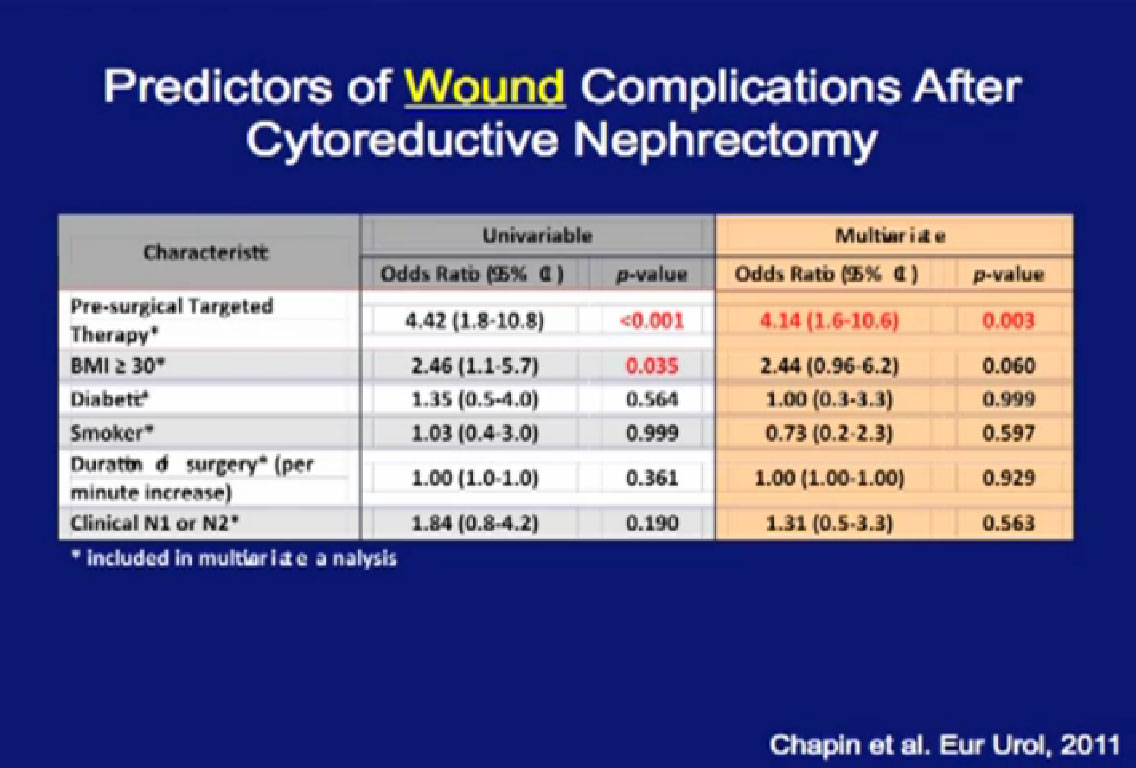

Looking at a multi-variate analysis, all the factors that predict for poor wound healing, the only factor that was significant was pre-surgical therapy.

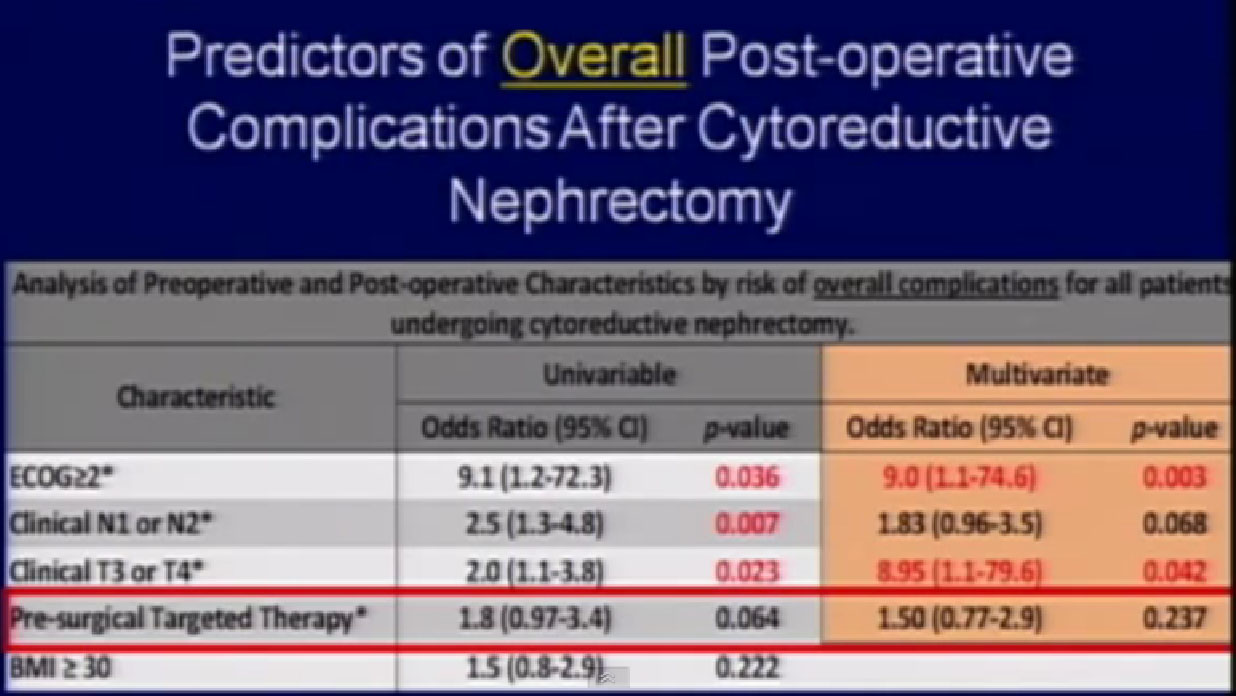

Thus patients who get this therapy before surgery have a higher risk of wound complications—but not a higher risk of overall complications. They have a higher risk of wound complications, but for overall complications, it is the exact same risk as patients who got upfront surgery.

Thus patients who get this therapy before surgery have a higher risk of wound complications—but not a higher risk of overall complications. They have a higher risk of wound complications, but for overall complications, it is the exact same risk as patients who got upfront surgery.

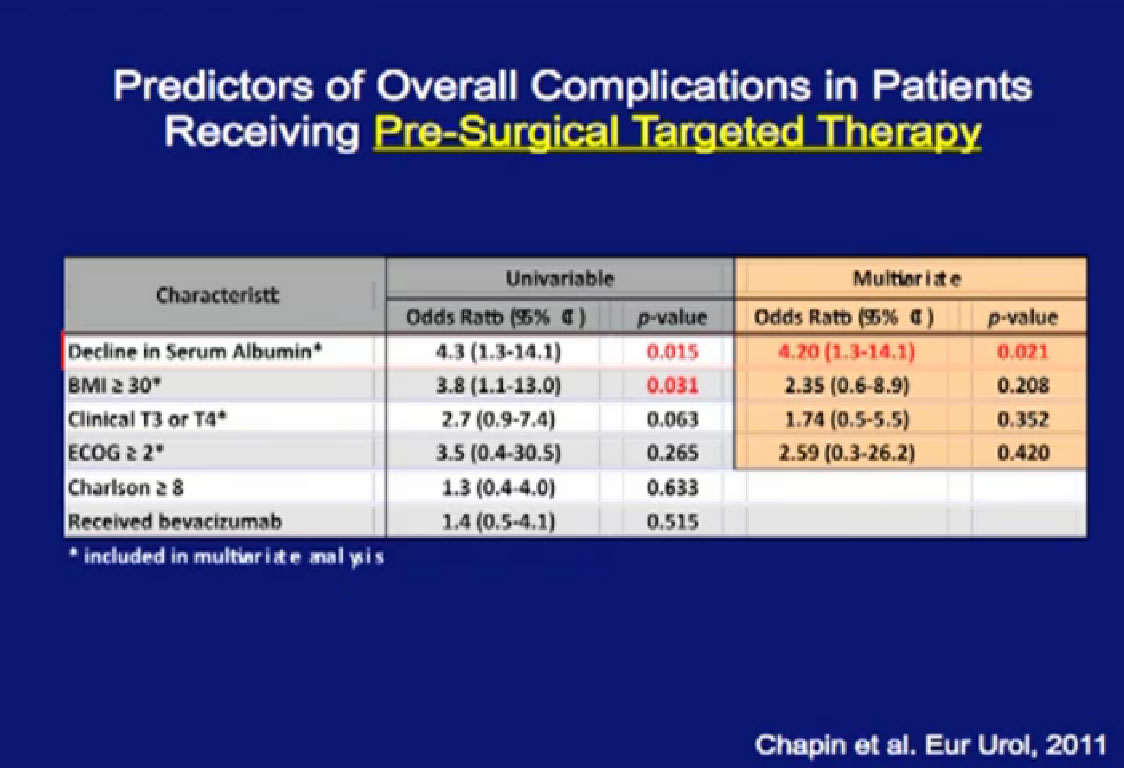

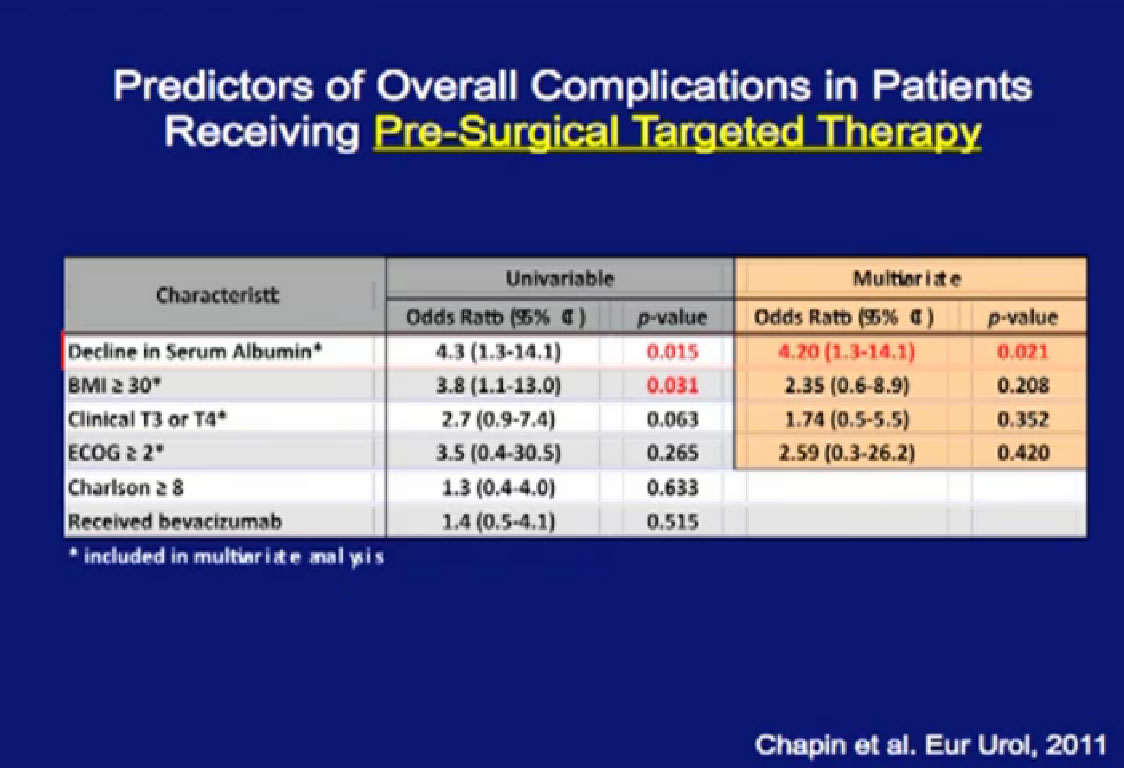

Patients who had a decline in their serum albumin while they were being treated had greater problems with wound complications. Serum albumin is seen as a marker for nutritional status. Now we follow that variable and find that for patients who have serum albumin decline, we are more likely to reinforce their wounds with surgery.

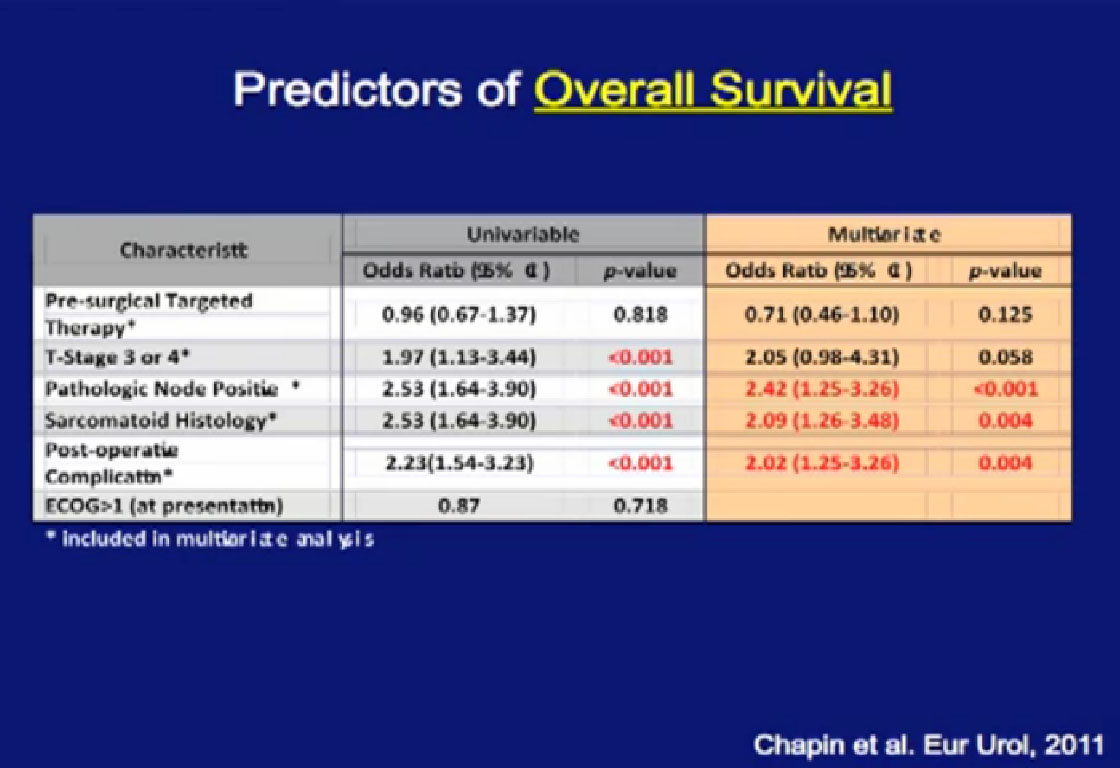

Happily, patients who received pre-surgical therapy did not have a worse survival than those who had upfront surgery, followed by systemic therapy. They may not do better, but they do not do worse, and that is an important feature and shown here graphically.

So What About Tumor Downstaging/Downsizing?

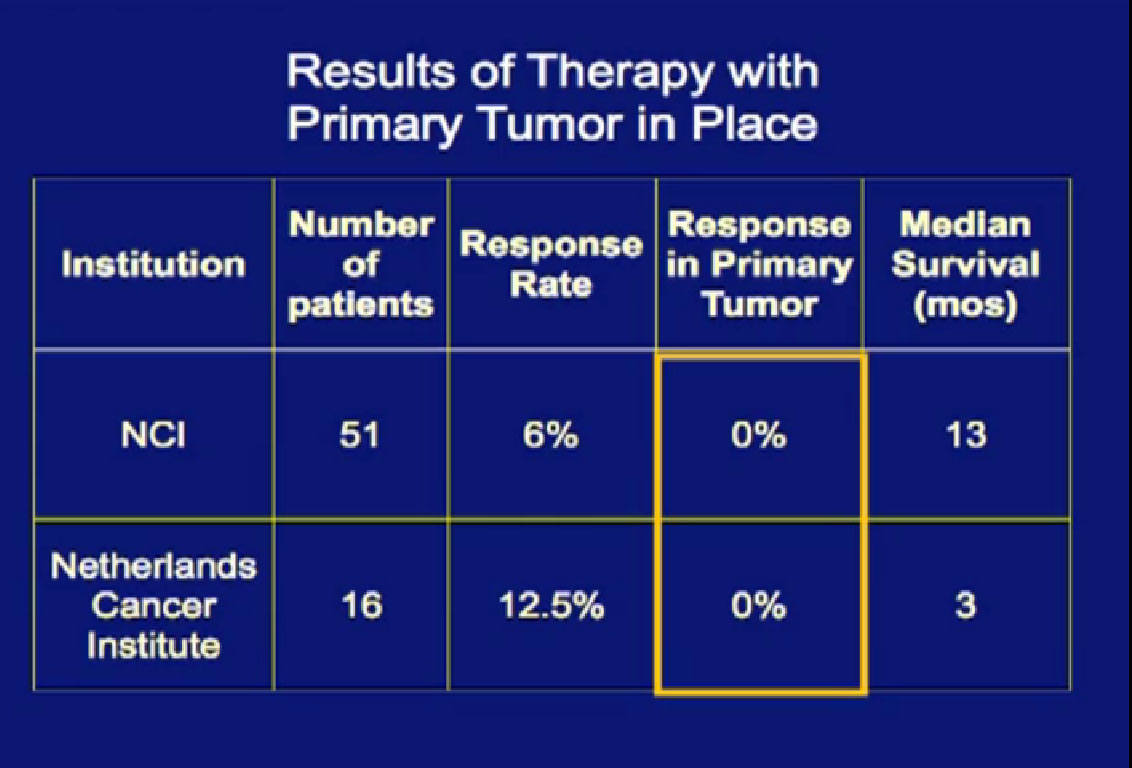

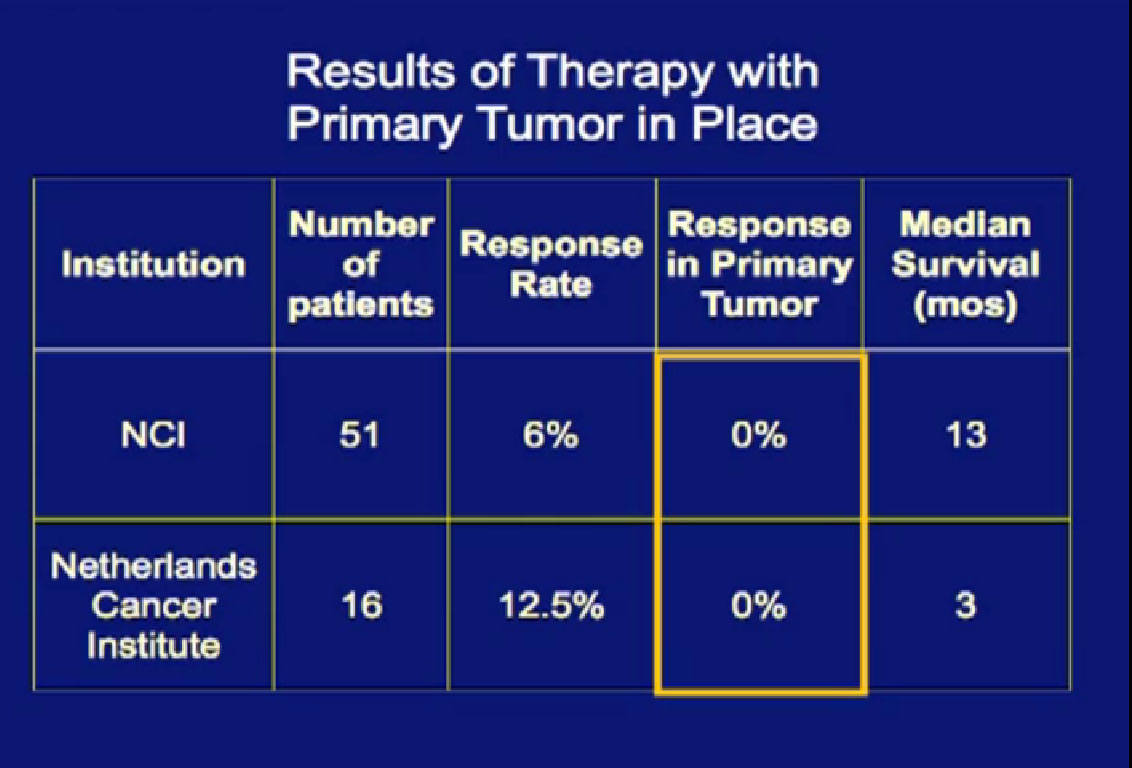

In the era of classical immunotherapy with interferon and IL2, with the primary tumor in place, the primary tumor never responded. That in part, was the impetus to take us to cytoreductive tumor, since the primary never responded.

These patients were treated here at MD Anderson. This is a patient had a very locally advanced tumor, and very large lymph nodes. Had this been done as cytoreductive upfront surgery, it would be a huge operation. Treated with Sunitinib and he had dramatic regression in the primary tumor, the nodes all went away, and he was able to have a laparoscopic nephrectomy. Arguably, he benefited from this approach.

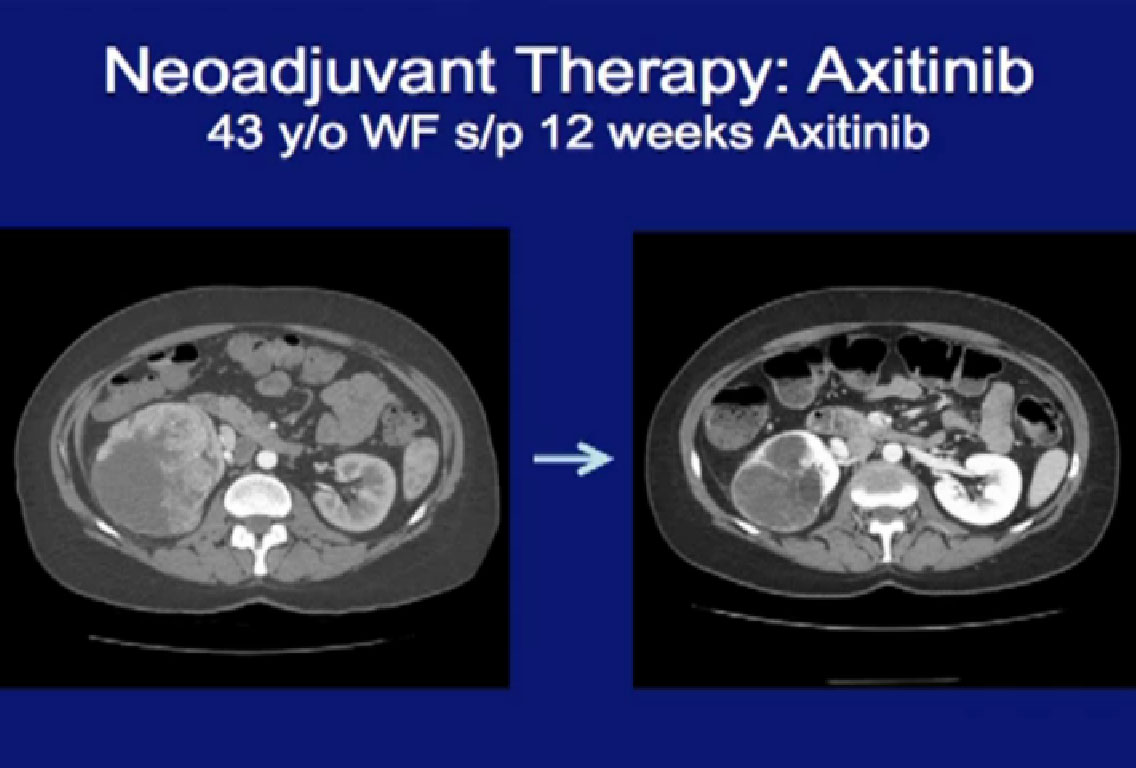

This patient was treated with Axitinib for a very large locally advanced primary tumor here, treated with Axitinib, (on right CT). On the right, there was dramatic regression of the tumor.

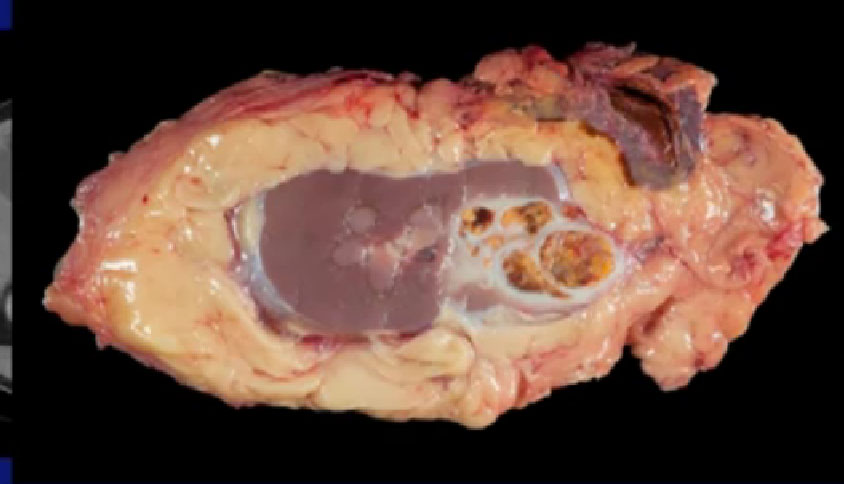

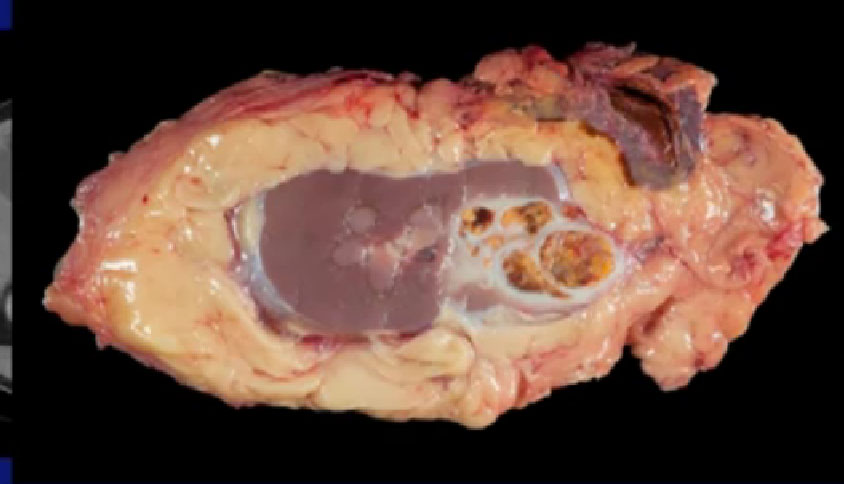

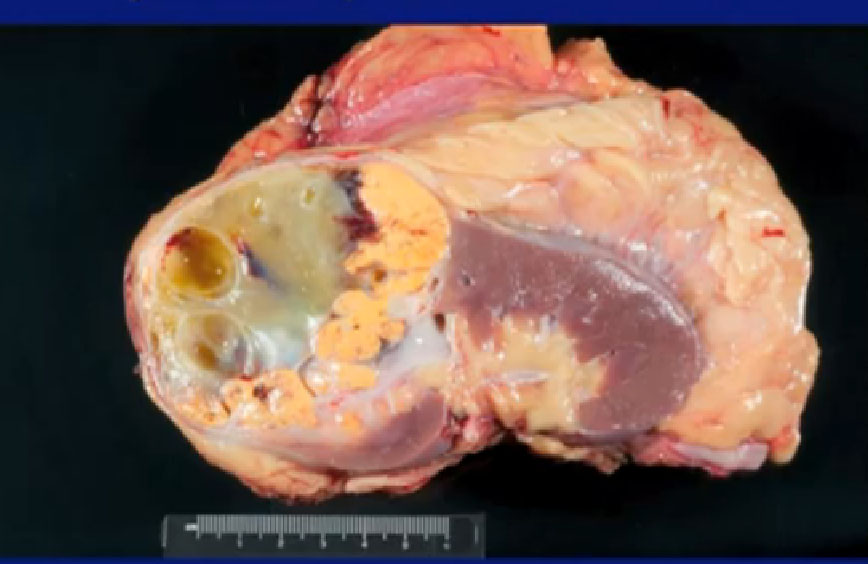

Here’s a look at the specimen we removed. Here is the tumor sitting in the kidney right here, and arguably, this patient could have been treated with a partial nephrectomy. We wanted to do that, but they were reluctant.

This is another patient treated with Axitinib, that received neoadjuvant therapy, and again you can see (on left) a very large locally advanced tumor sitting in the right kidney. He received Axitinib and after three months, and you see a dramatic regression (right CT). With this he would have had to receive an open nephrectomy and with this, this patient can undergo a laporascopic nephrectomy. Much less morbid.

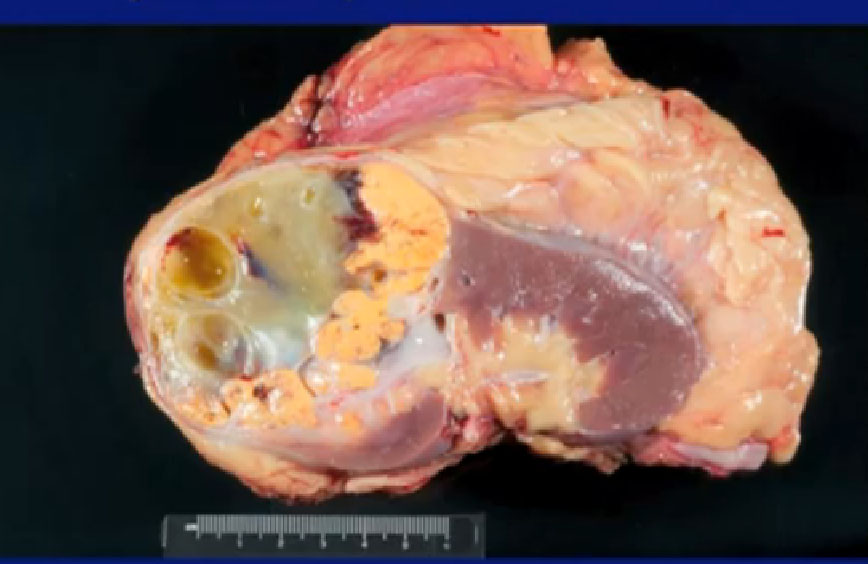

Here’s a picture of the specimen, dramatic improvement. All of this used to be viable tumor, nowhas been killed by the Axitinib and this rim is the tumor present.

Are These Just Anecdotes, or Can We Rely on These Agents to Downstage Tumors?

I would argue that if it is true, as a surgeon, I would say, give it to everybody. Maybe we can offer partial nephrectomies to all our patients.

S

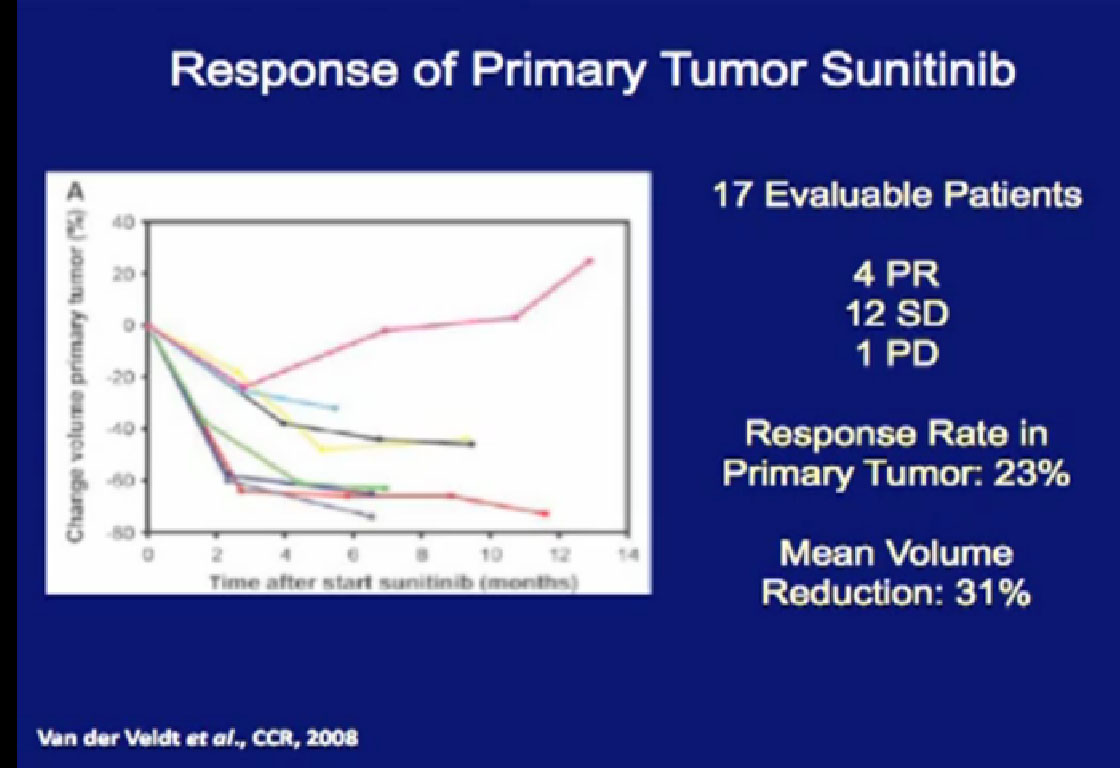

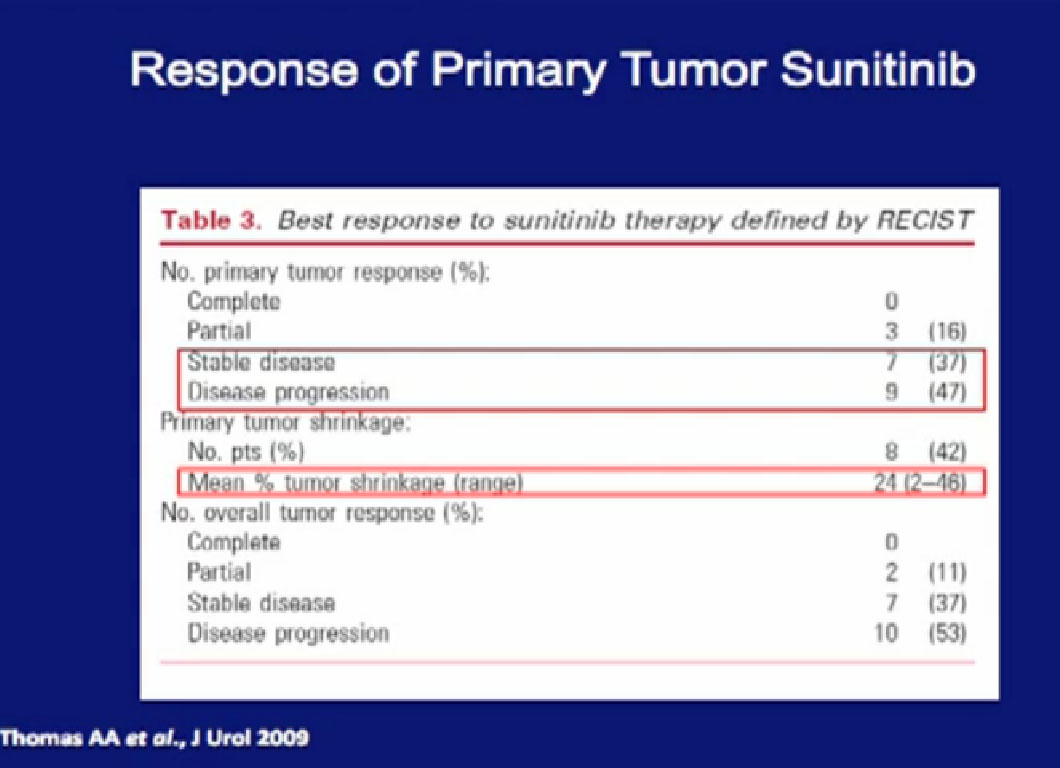

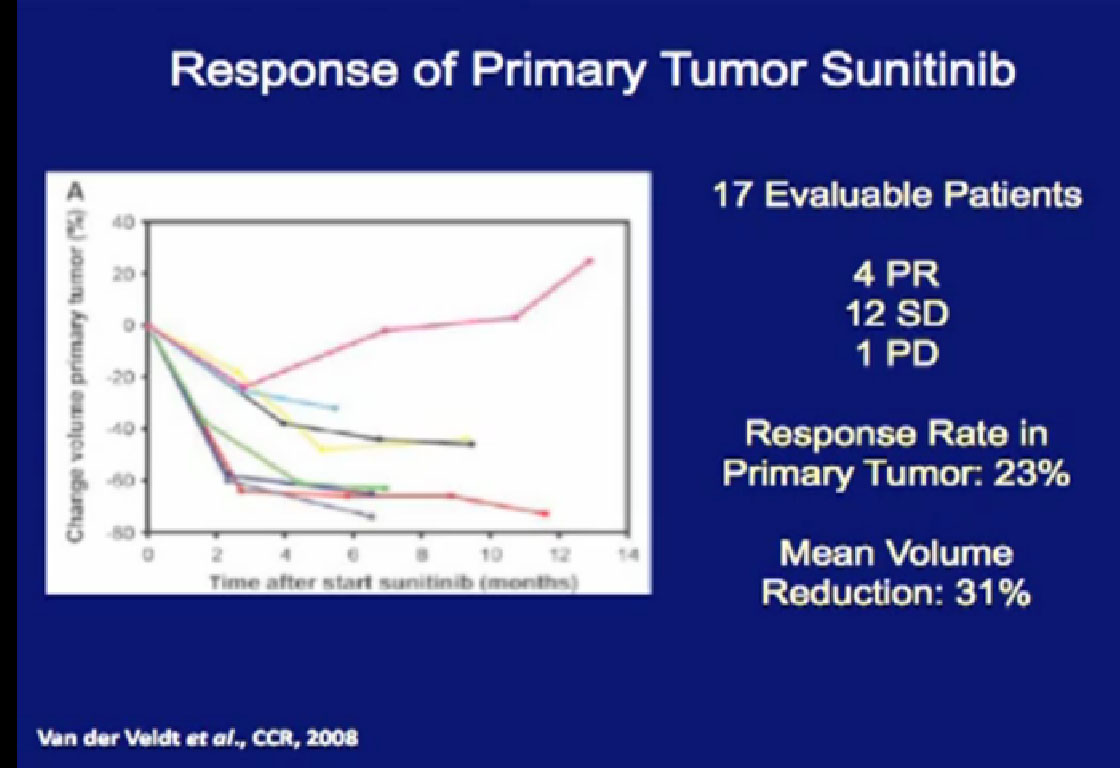

So what is the data? This study looked at 17 patients treated with their primary tumor in place with Sunitinib. Only 23% of the patients actually demonstrated had a response, but those that did had a response rate of 31%.

So what is the data? This study looked at 17 patients treated with their primary tumor in place with Sunitinib. Only 23% of the patients actually demonstrated had a response, but those that did had a response rate of 31%.

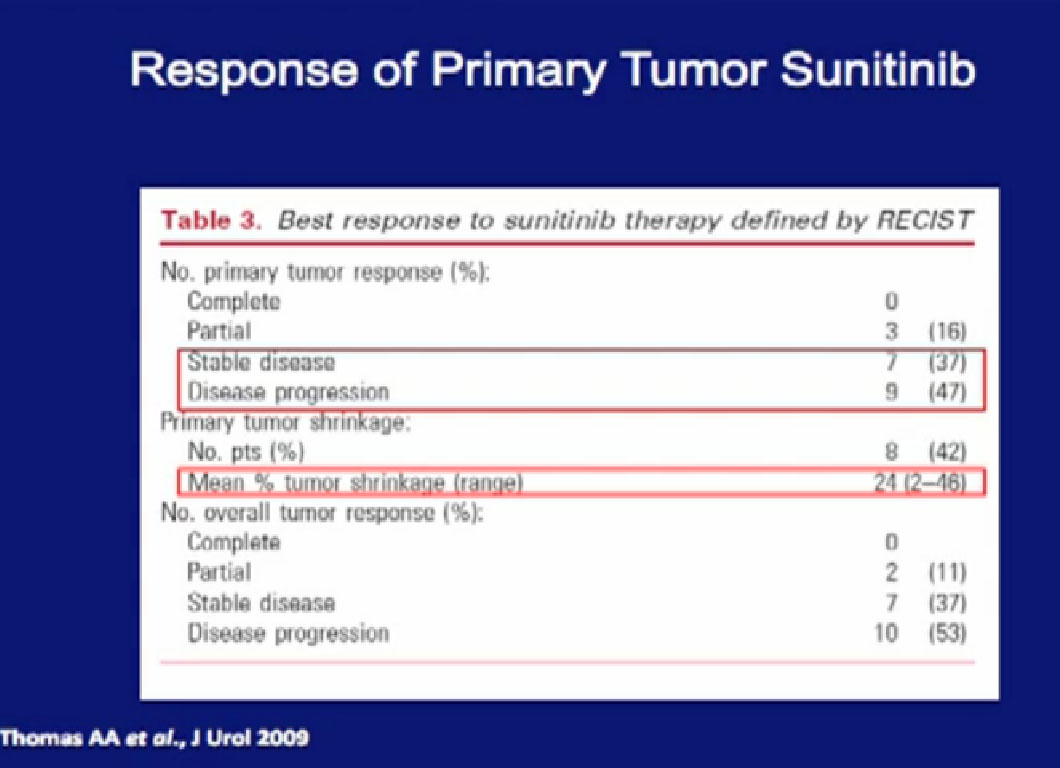

At the Cleveland Clinic, the patients were treated with Sunitinib, and the overwhelming majority had little or no response in their primary tumor. In some patients, their tumor grew while on treatment.

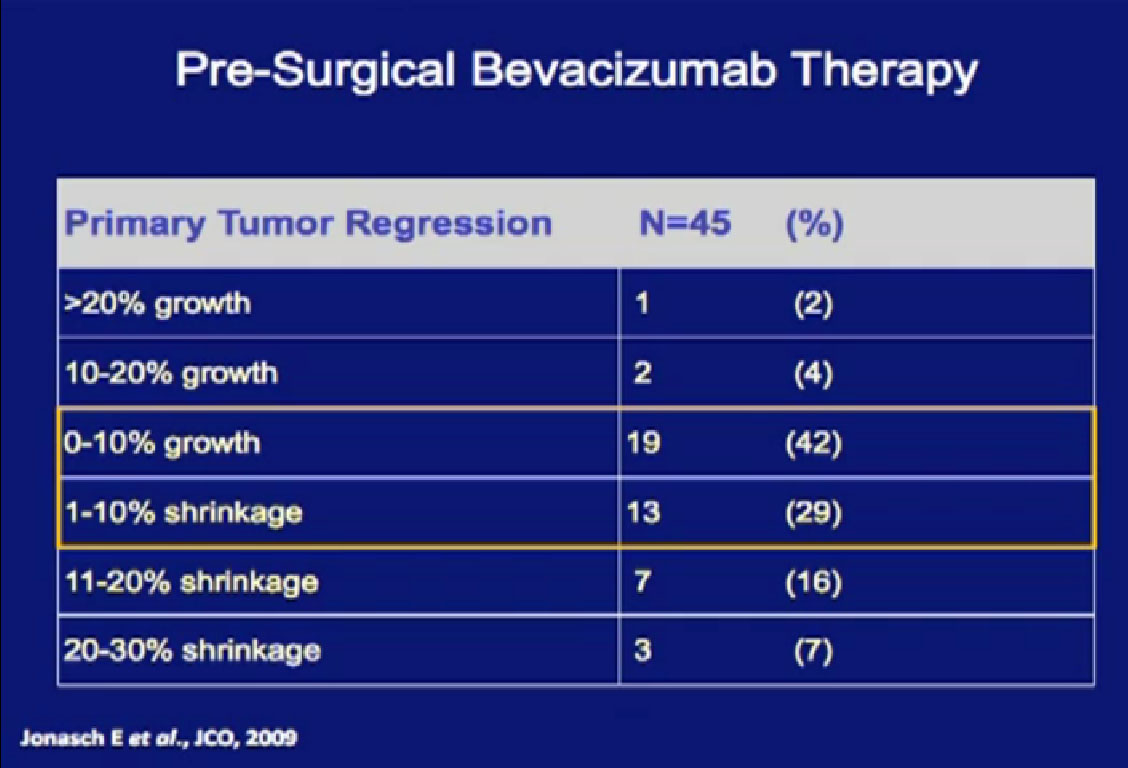

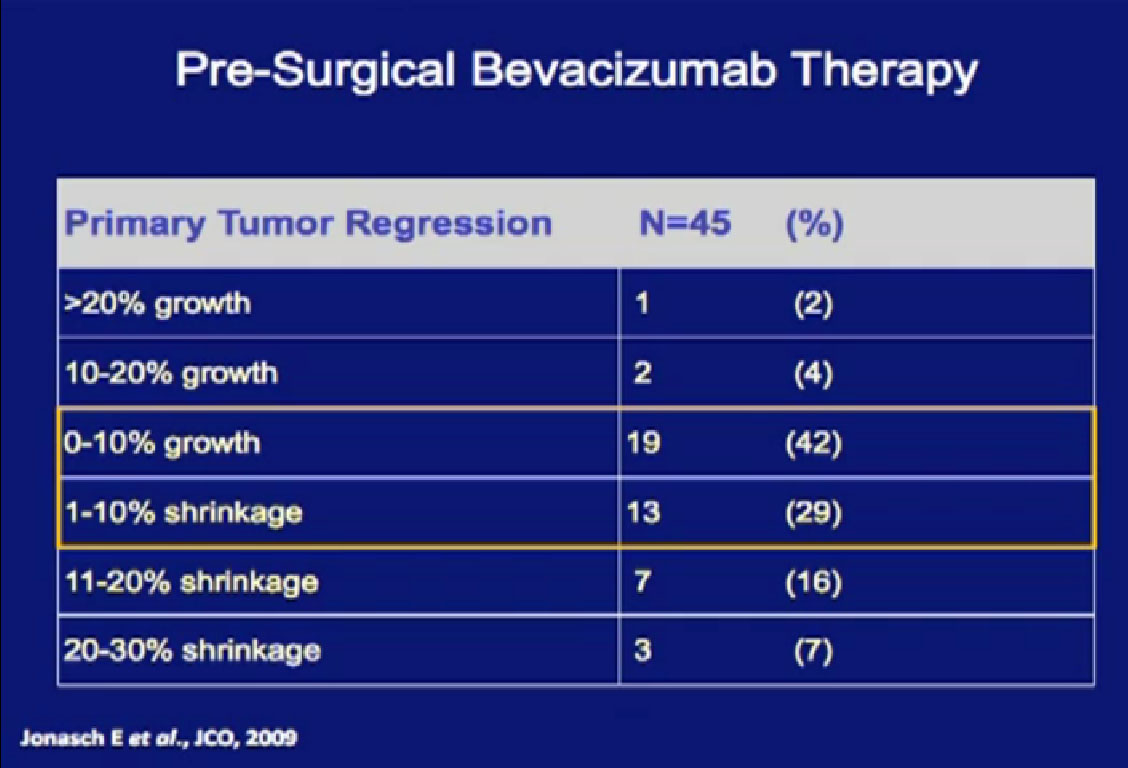

Data from our Bevacizumab trial shows the recurrent theme; the overwhelming majority of patients had little or no response in their primary tumor to targeted therapy.

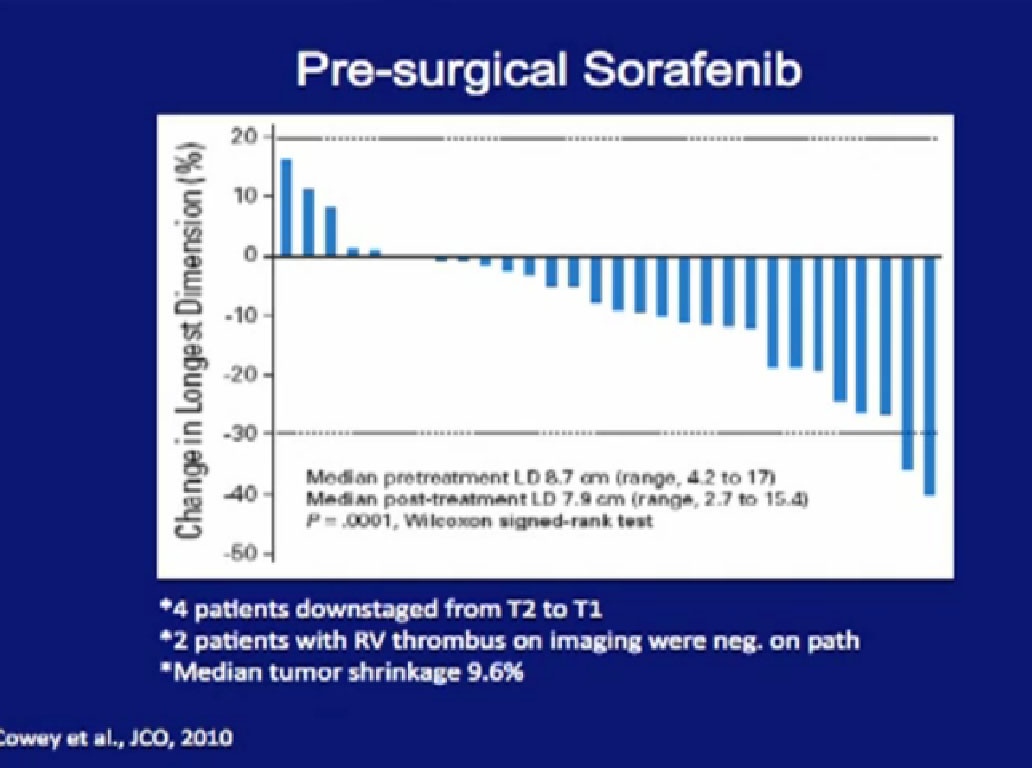

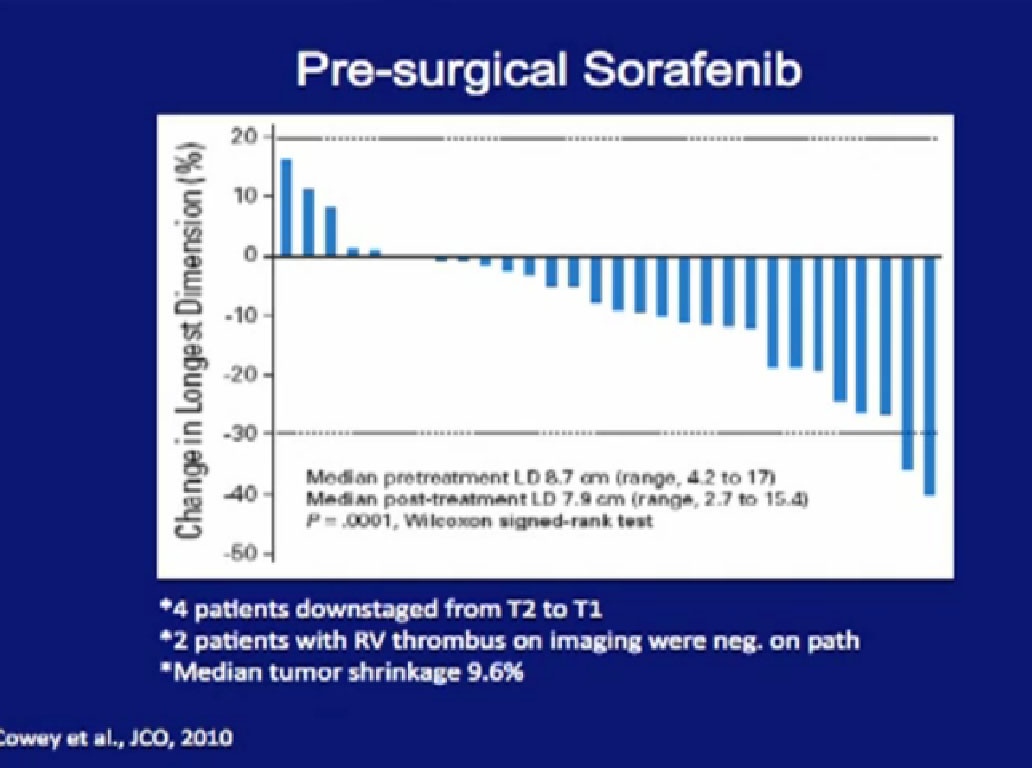

The University of North Carolina tested Sorafenib. Again, there were some dramatic regressions, there were some dramatic progressions, but the vast majority of patients had little or no response in their primary tumor.

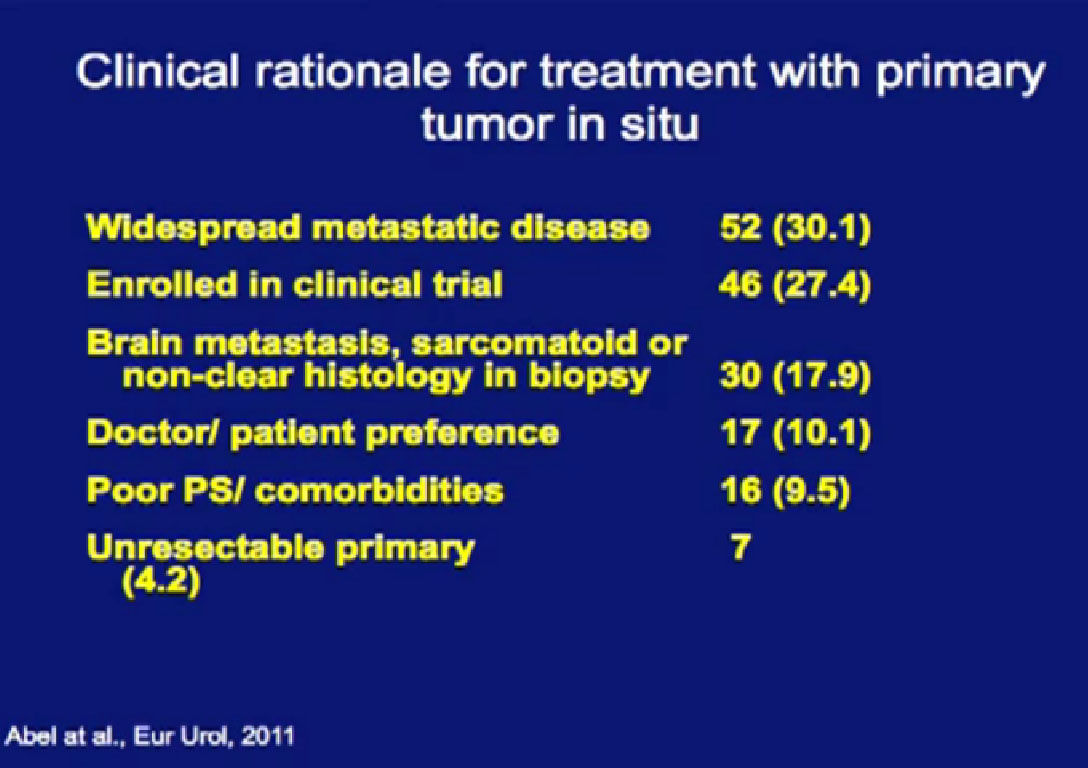

Trying to determine once and for all, we want to ask whether there should be this treatment with the tumor in place.

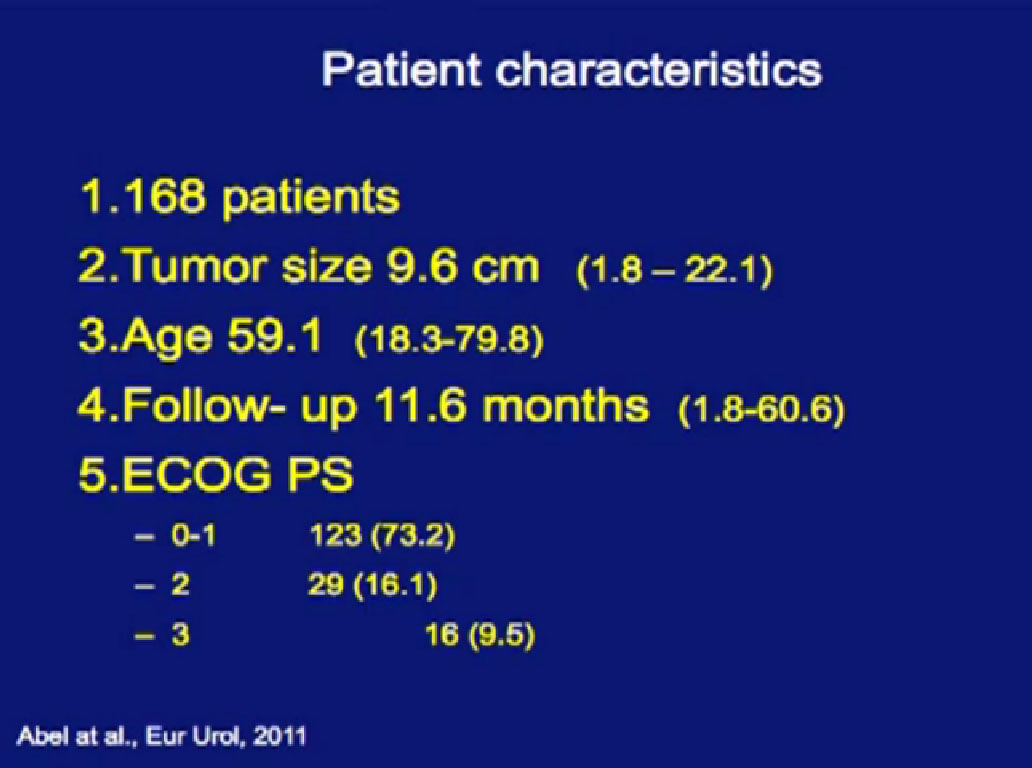

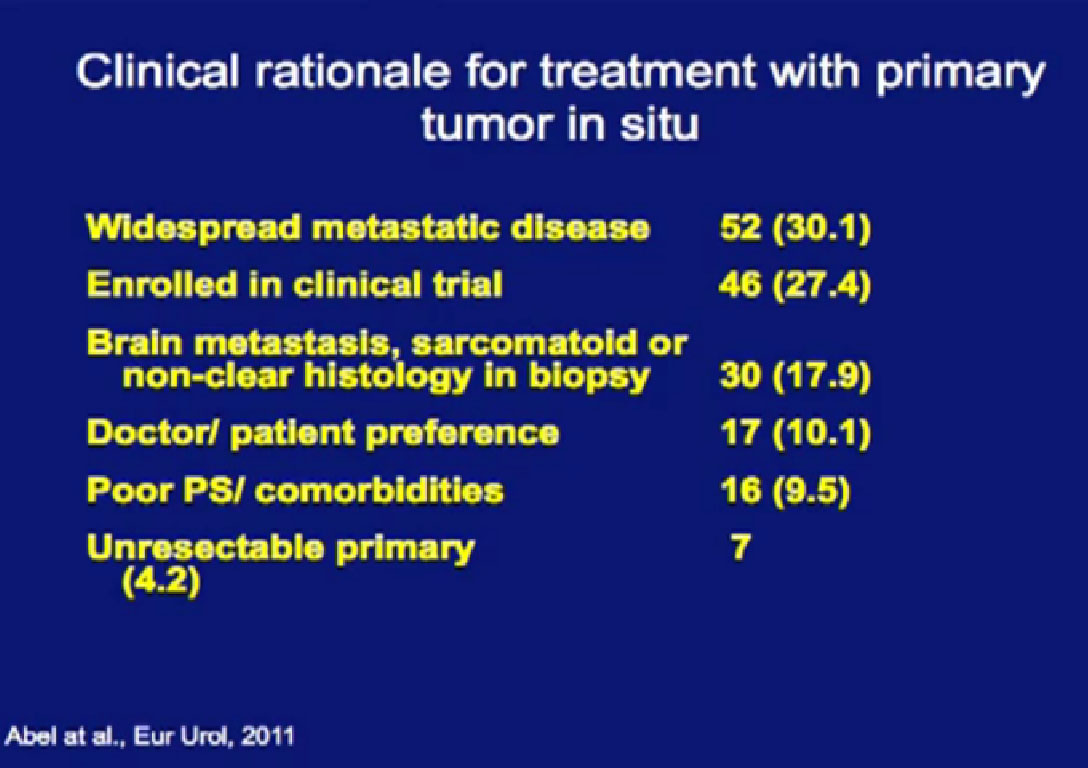

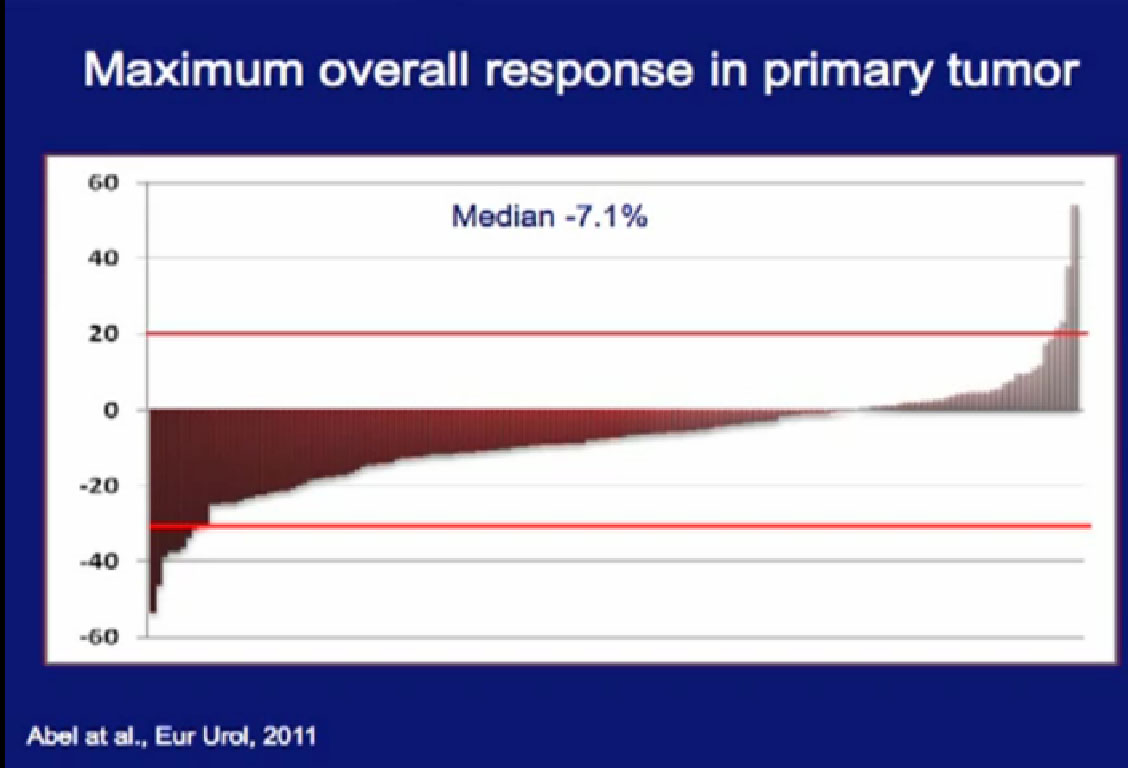

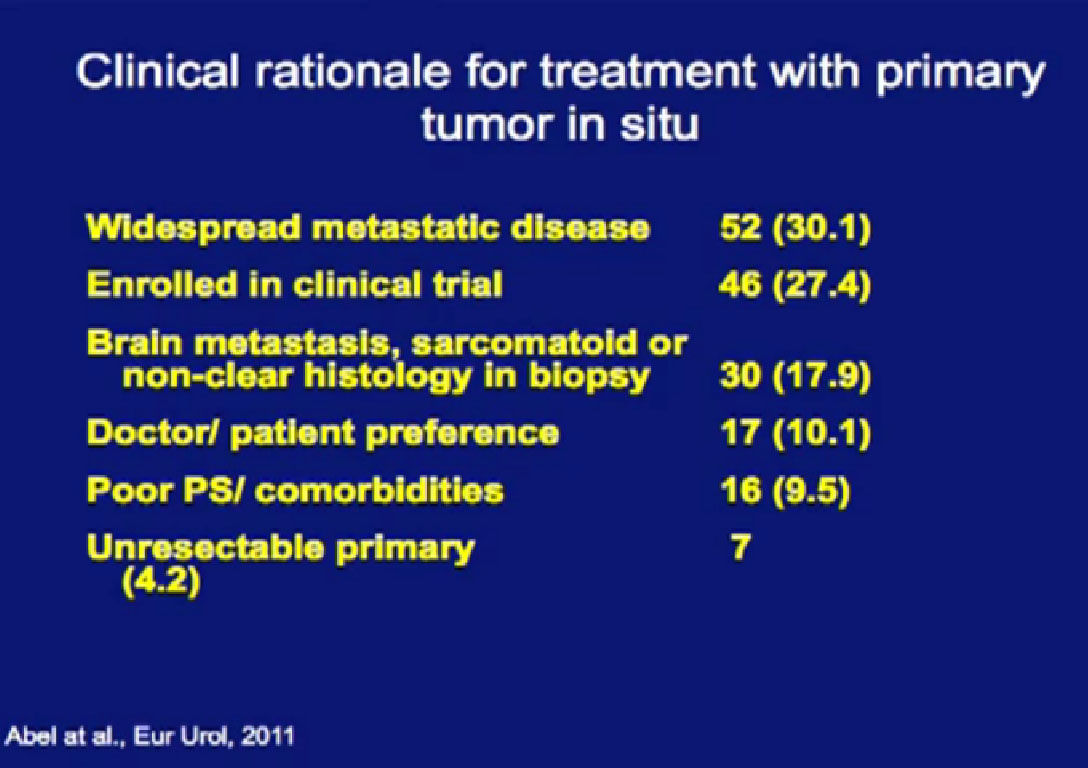

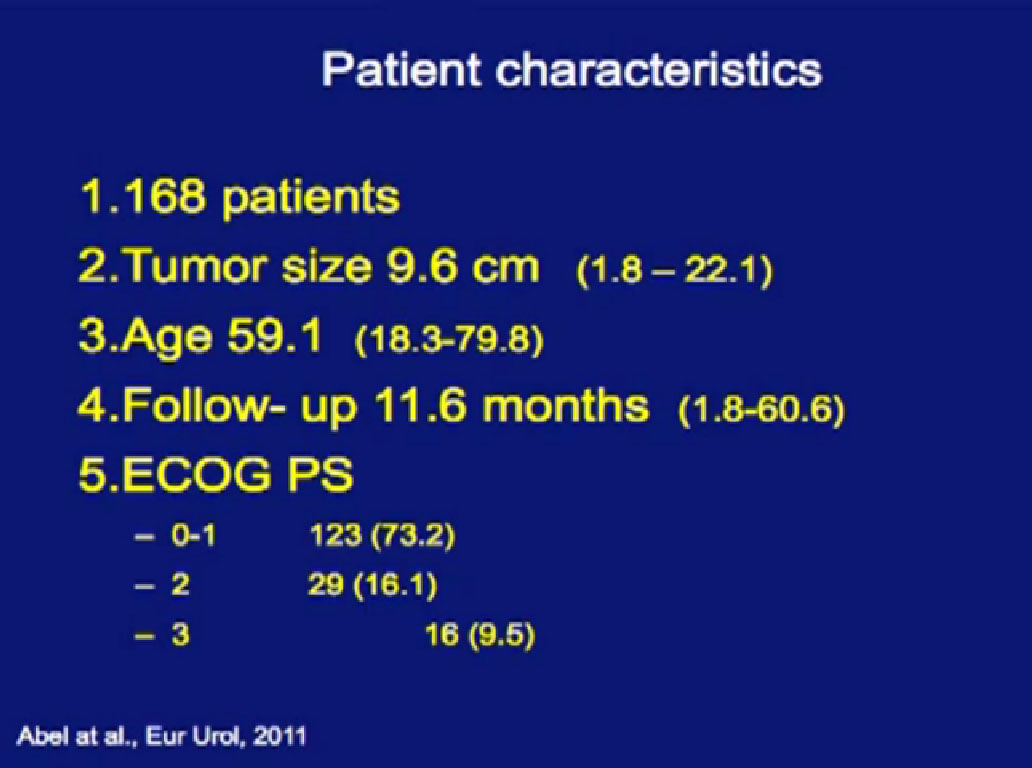

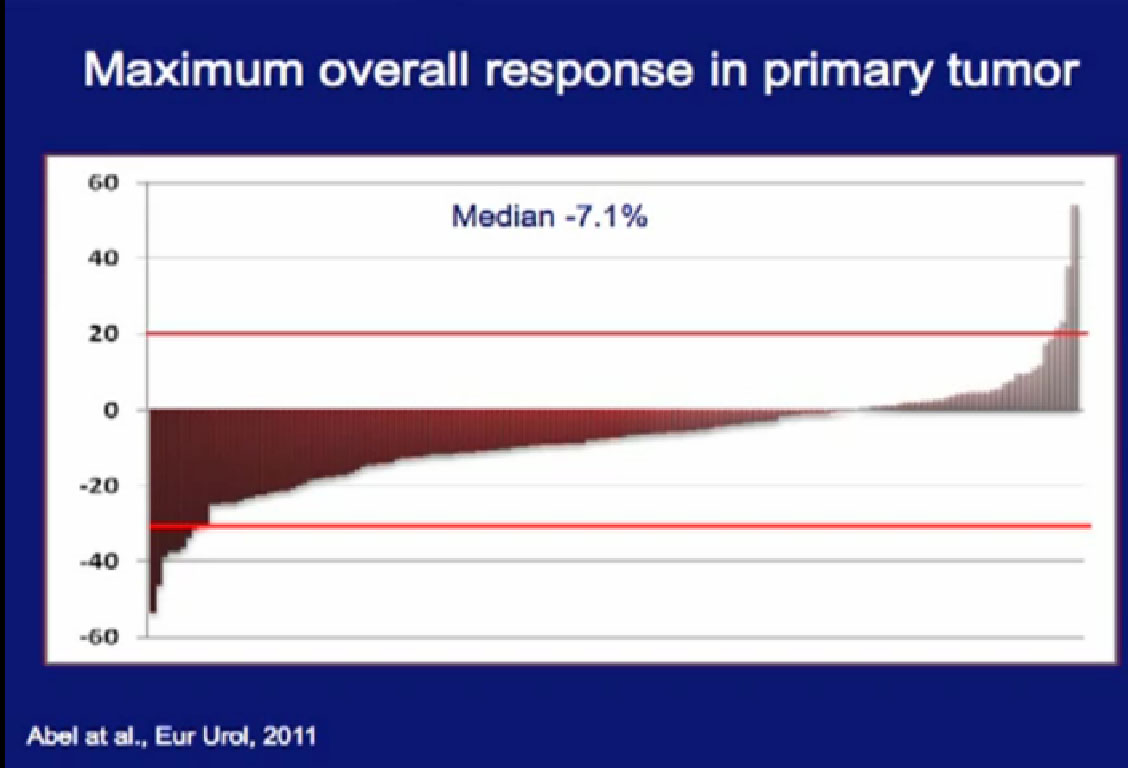

In a larger study of 168 patients treated with tumor in place, we looked to see there would be tumor shrinkage.

In a larger study of 168 patients treated with tumor in place, we looked to see there would be tumor shrinkage.

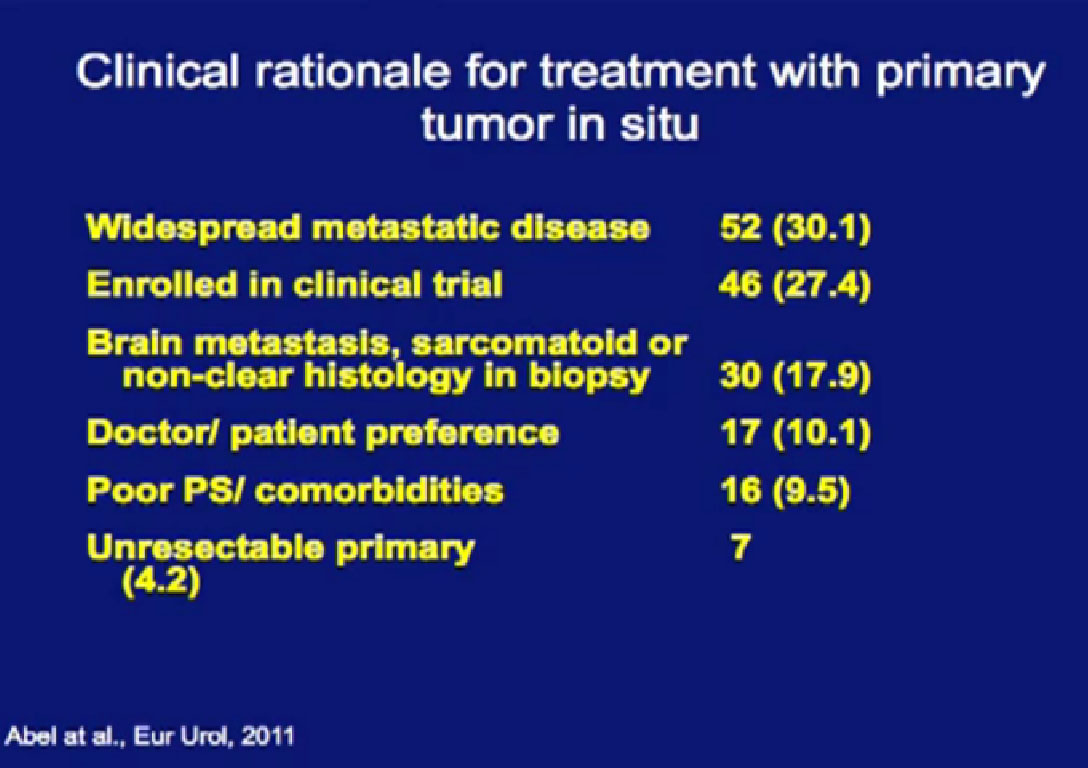

Reasons for not removing the tumor is below, with the vast majority not considered good candidates for surgery, or were enrolled in a clinical trial.

These were the therapies they received. The vast majority received Sunitinib, which is the frontline standard of care, with other therapies intermingled.

As to the response rates, we had some patients who had dramatic progression of their tumor, some patients who had dramatic regression of their tumor. The vast majority of the patients had little or no response in their primary tumor.

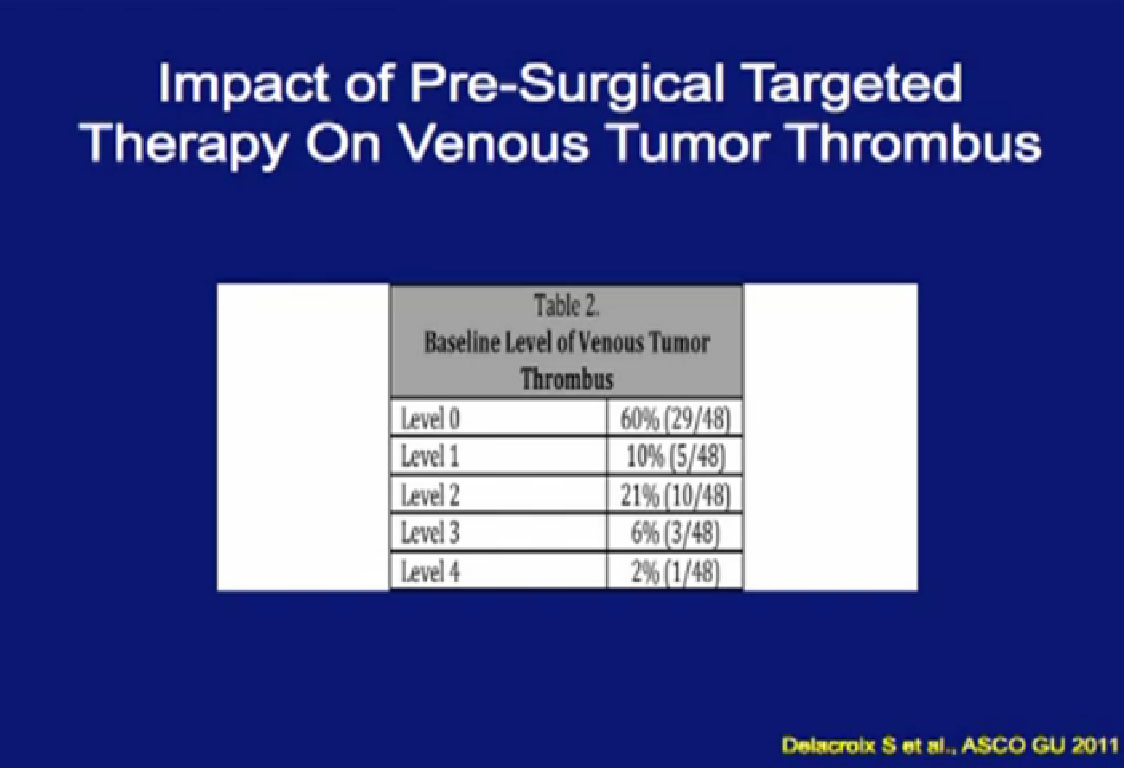

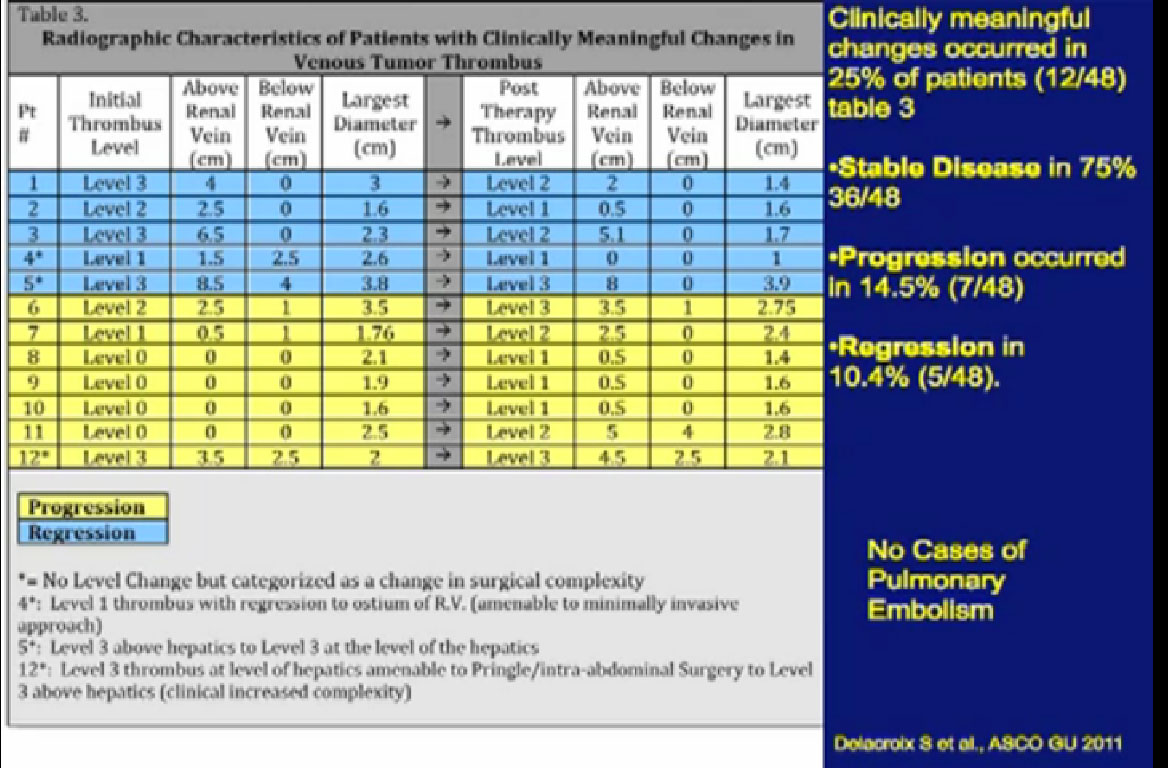

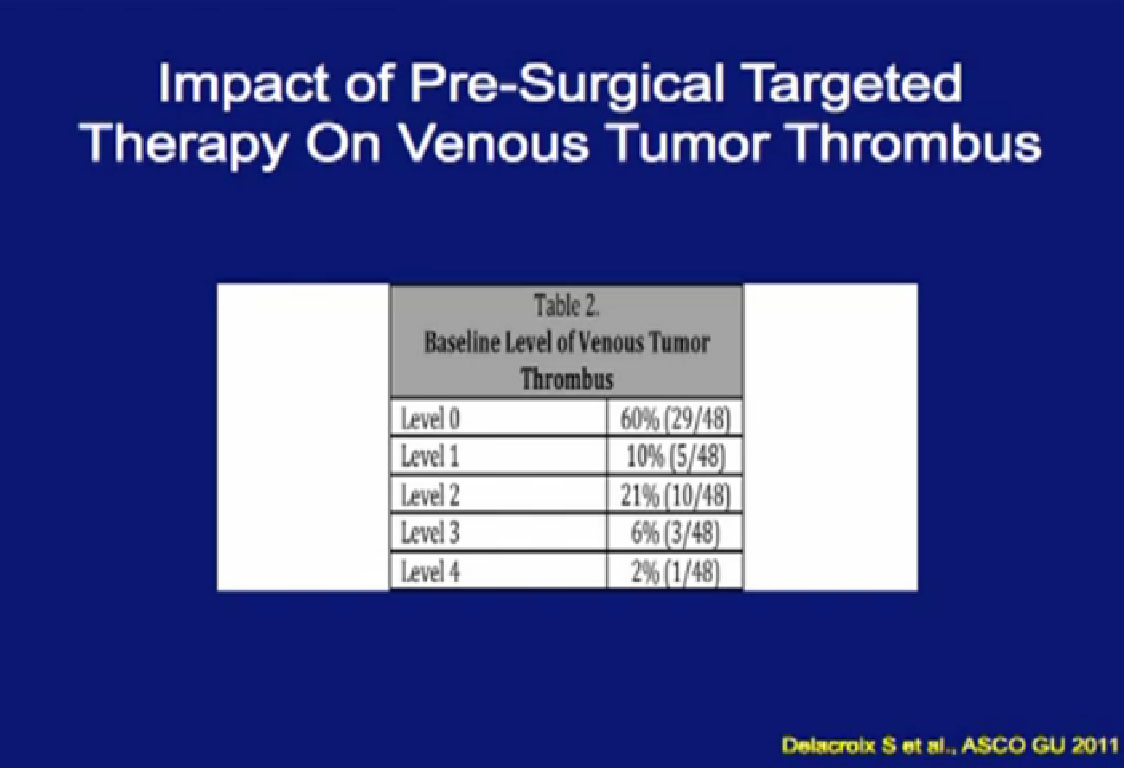

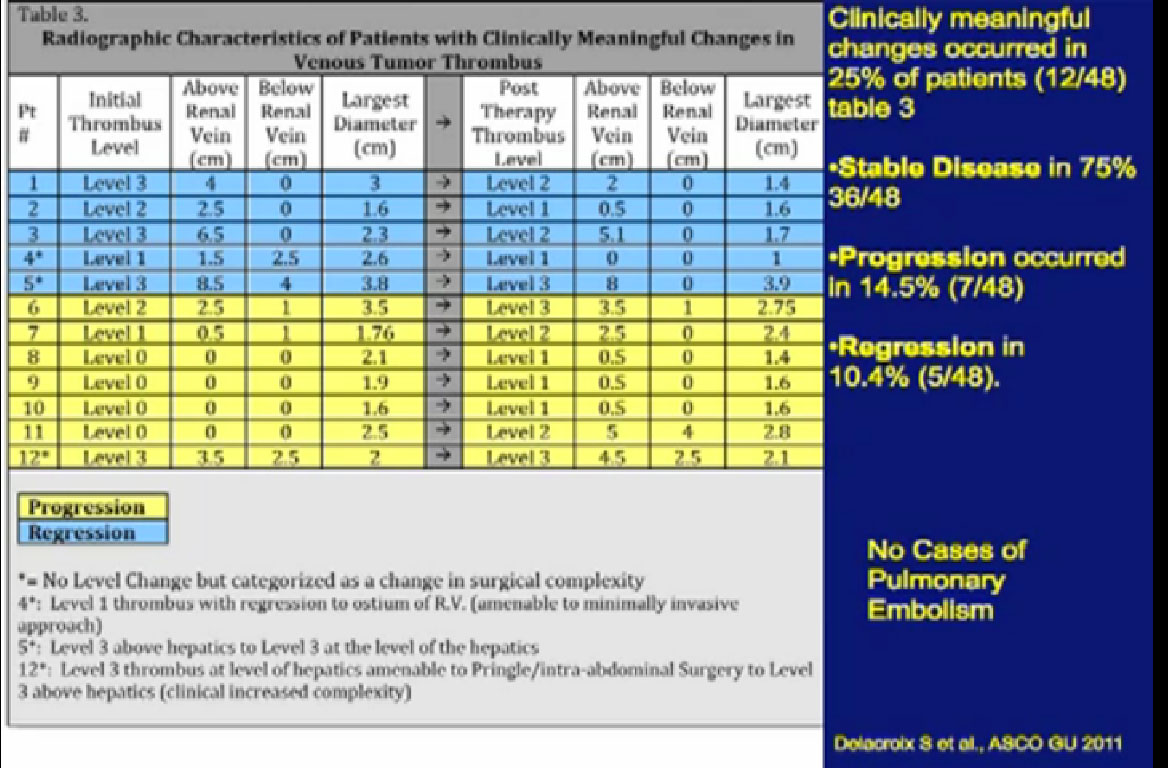

One of the things that is common in the community is that patients with large venous tumor thrombi may hear their community oncologist say, “Here, take this medication, it will shrink your thrombus and it will make your surgery easier.” So is this data true?

A significant patients will present to me on Sunitinib. In this series, 48 patients had different levels of tumor thrombi and were treated with these agents.

Unfortunately, a recurrent theme (references “Stable Disease in 75%), patients had little or no response in their tumor thrombus. In fact, 15% of patients progressed while in treatment. Only 10% of patients demonstrated shrinkage in their venous thrombus in response to treatment.

Initial Body of Evidence Would Suggest that Significant Primary Tumor Downstaging Will NOT Be Realized with the Current Generation of Targeted Therapy Agents

I would suggest that the initial body of evidence suggests that significant primary tumor downstaging will not be realized with the current generation of targeted therapy. Nevertheless I must confess that I have been quite impressed with the responses that we have been seeing with Axitinib. Every patient has had a response.

As to the report card on presurgical/neoadjuvant therapy. I would argue that it is indeed safe. We see more wound complications, but those are pretty easily dealt with. It does not seem to reliably downsize tumors. I would this does not. Is this worth doing? Should we continue to do this clinical research at MD Anderson and around the world to determine if neoadjuvant therapy has a role in the treatment of patients? I would argue that it does for the following reasons.

In our Bevacizumab trial, 50 patients were enrolled, but only 42 underwent nephrectomy. Six patients had disease progression and went on to salvage systemic therapy rather than nephrectomy. These six patients were saved from a surgery that would not benefit them.

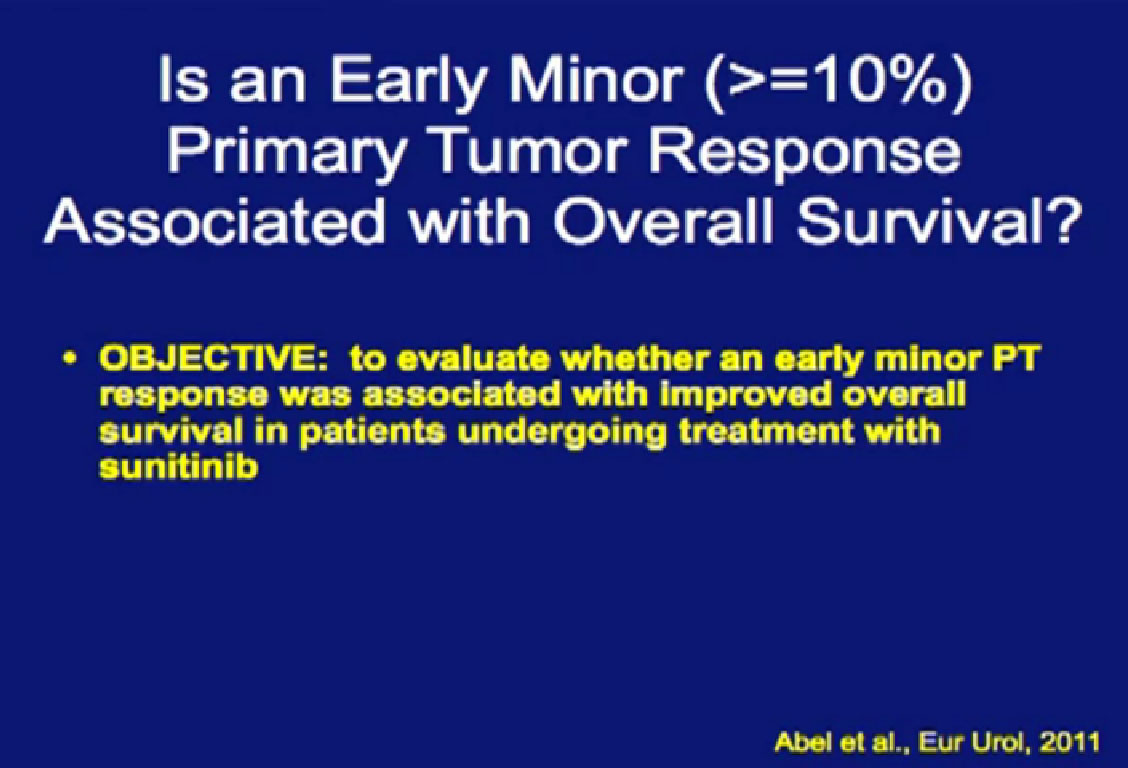

In our series, we asked, “Is there something about pre-surgical therapy that we can use to predict prognosis, and can we use the primary tumor as a bio-marker to predict outcome?”

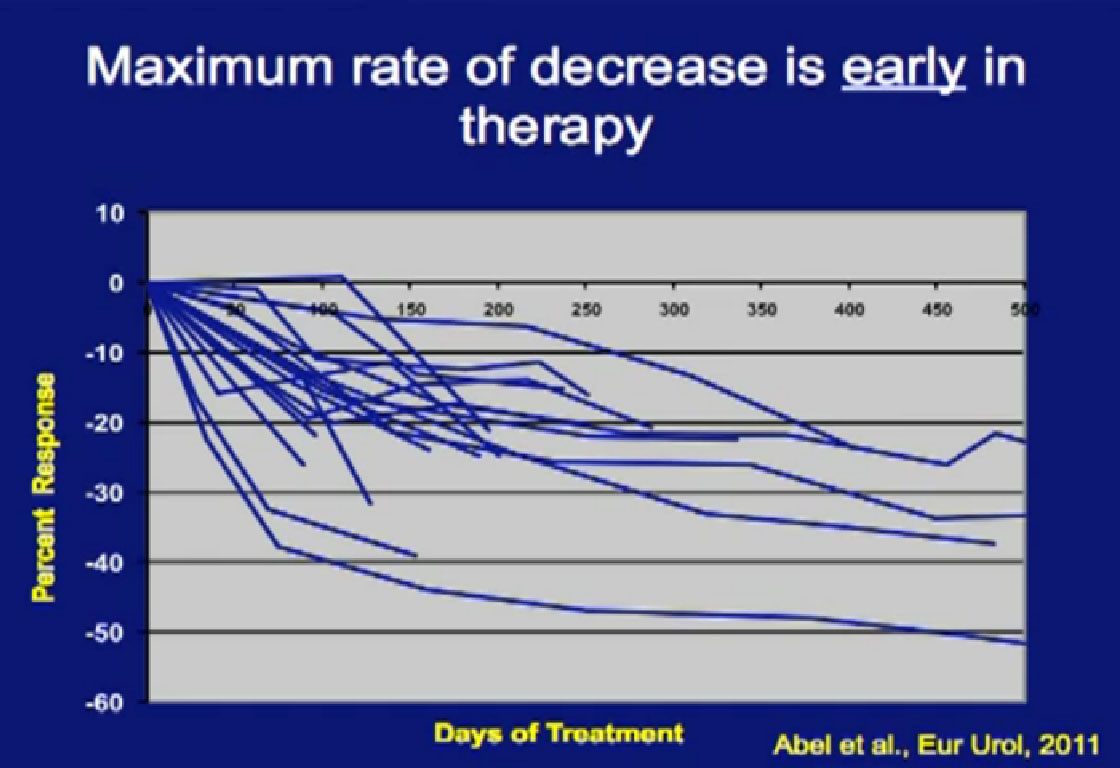

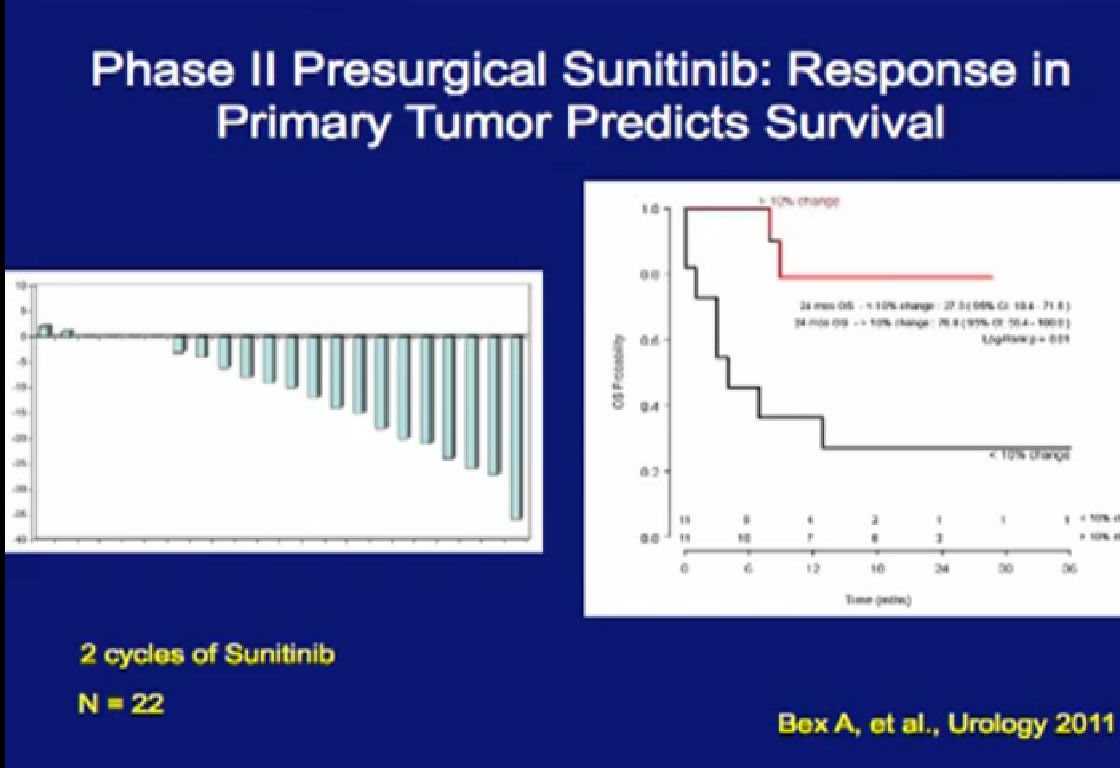

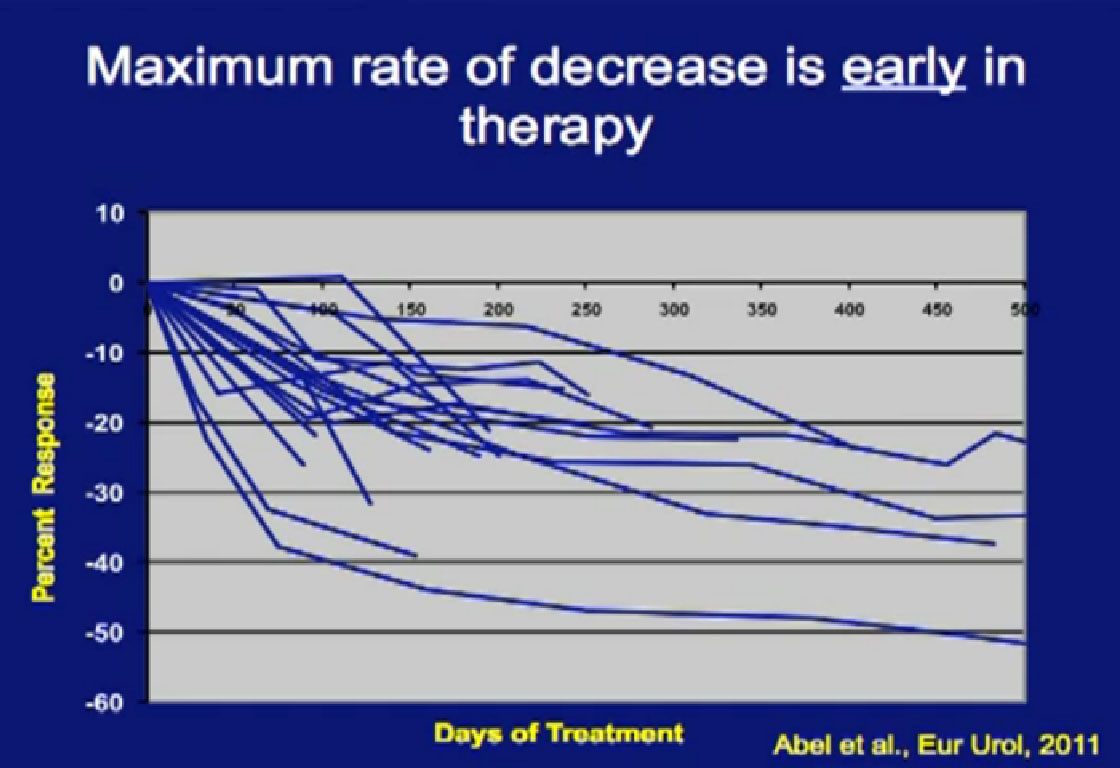

This is a spidergram looking at primary response in the tumor. We noted is that patients, who did respond in their primary tumor, they responded early. If you don’t see it early, you will not see it; there is no sense to continue treatment if you don’t see some shrinkage.

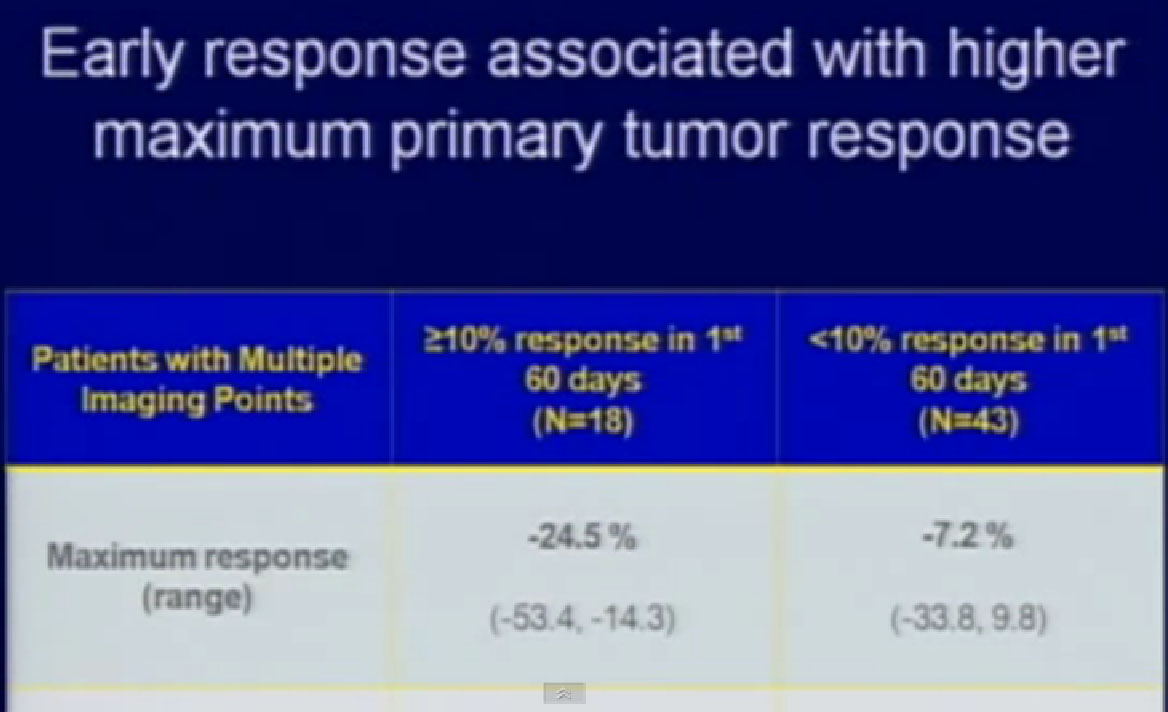

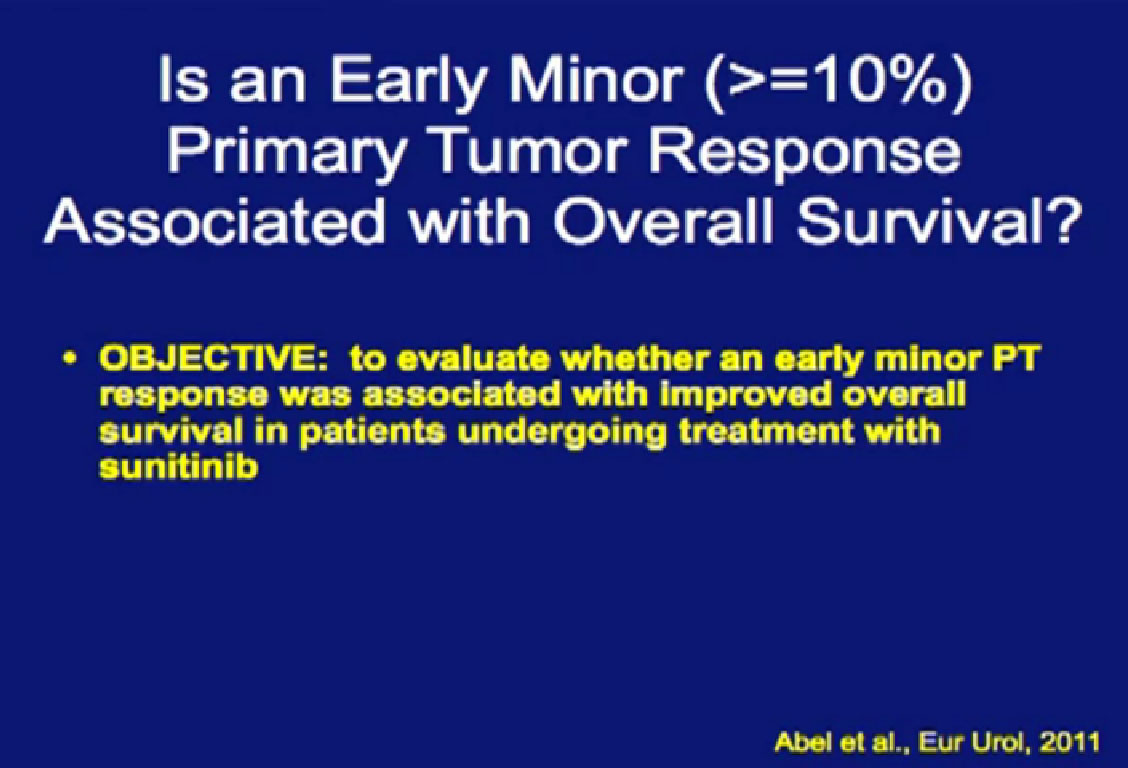

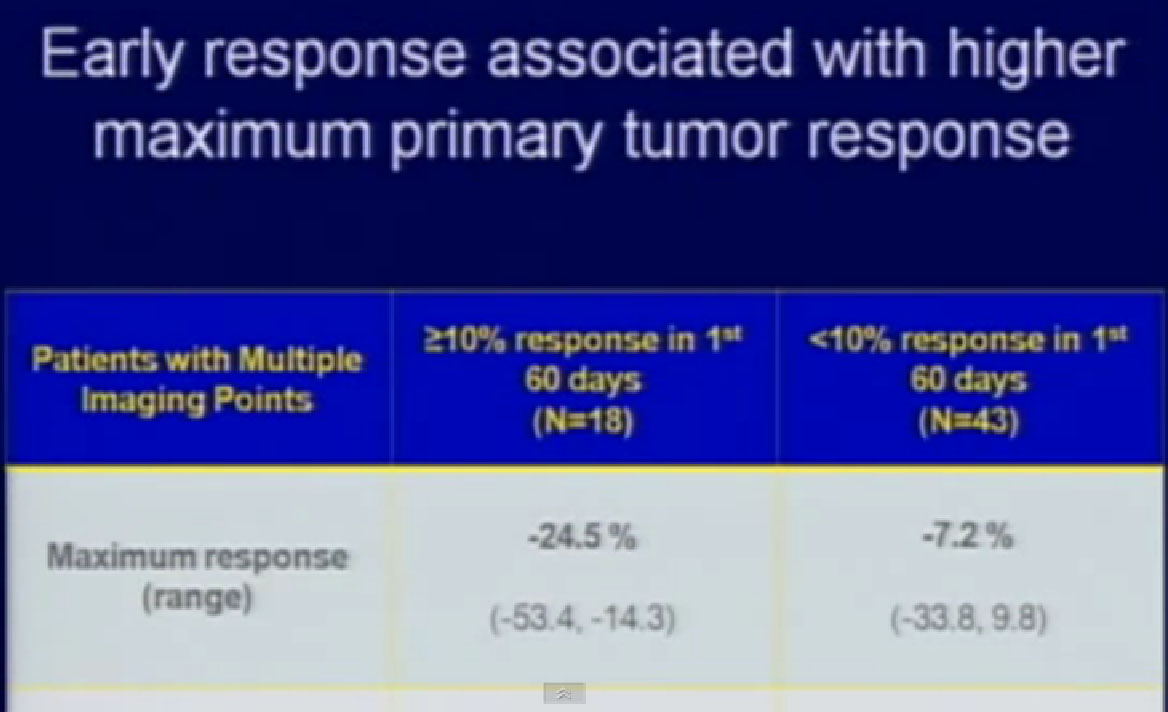

Those patients who had at least a 10% reduction (in the first 60 days) in their primary tumor size went on to have their tumor shrink almost 25%. If patients did not have that 10% in the first 60 days, they were likely to have little, if any response.

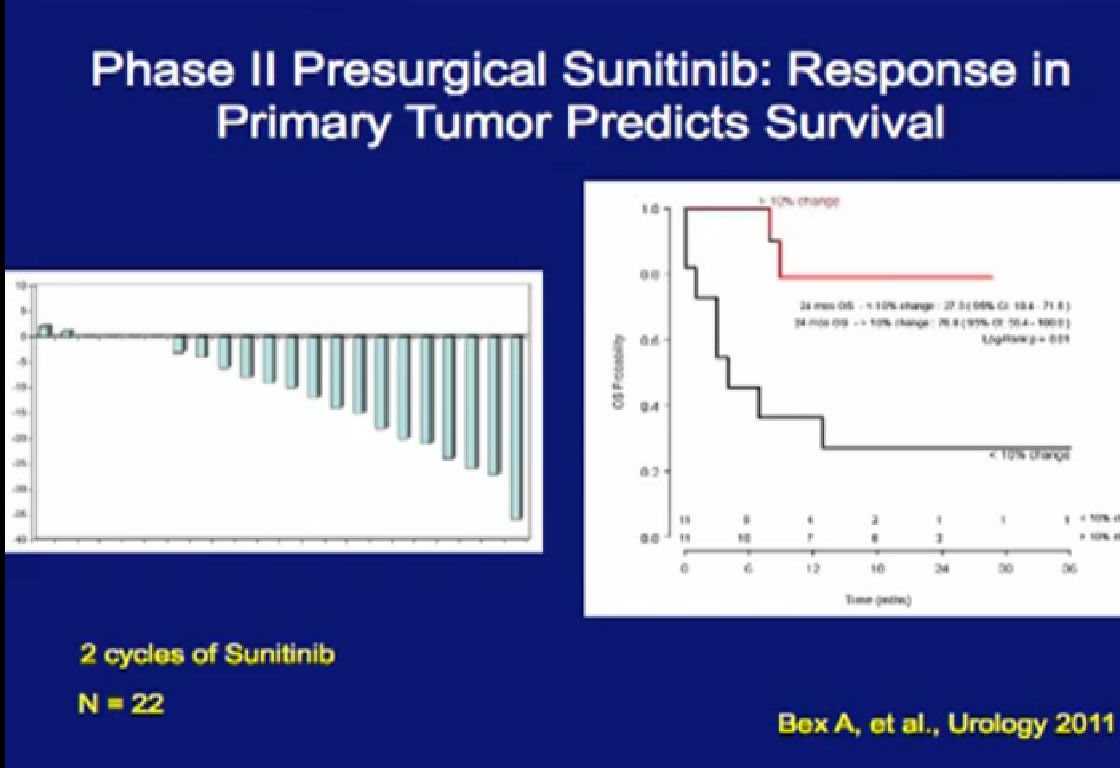

So we could predict who was going to respond in the primary tumor, so the question was, “Can we use that as some sort of bio-marker?”

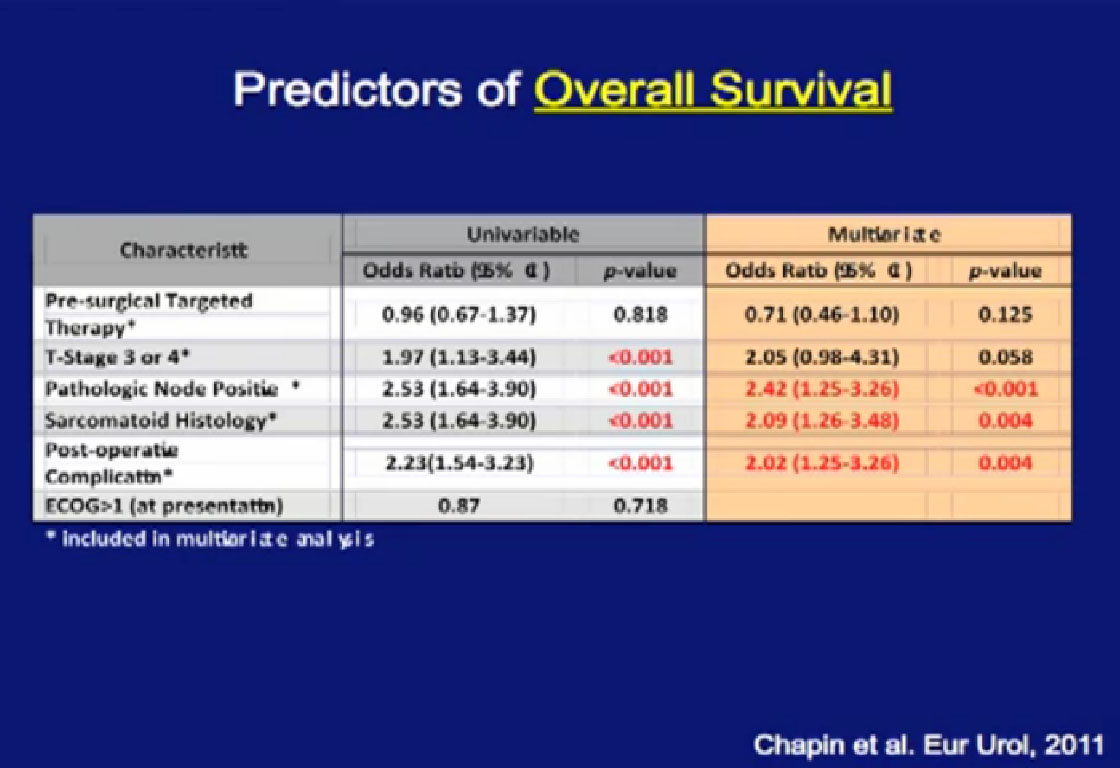

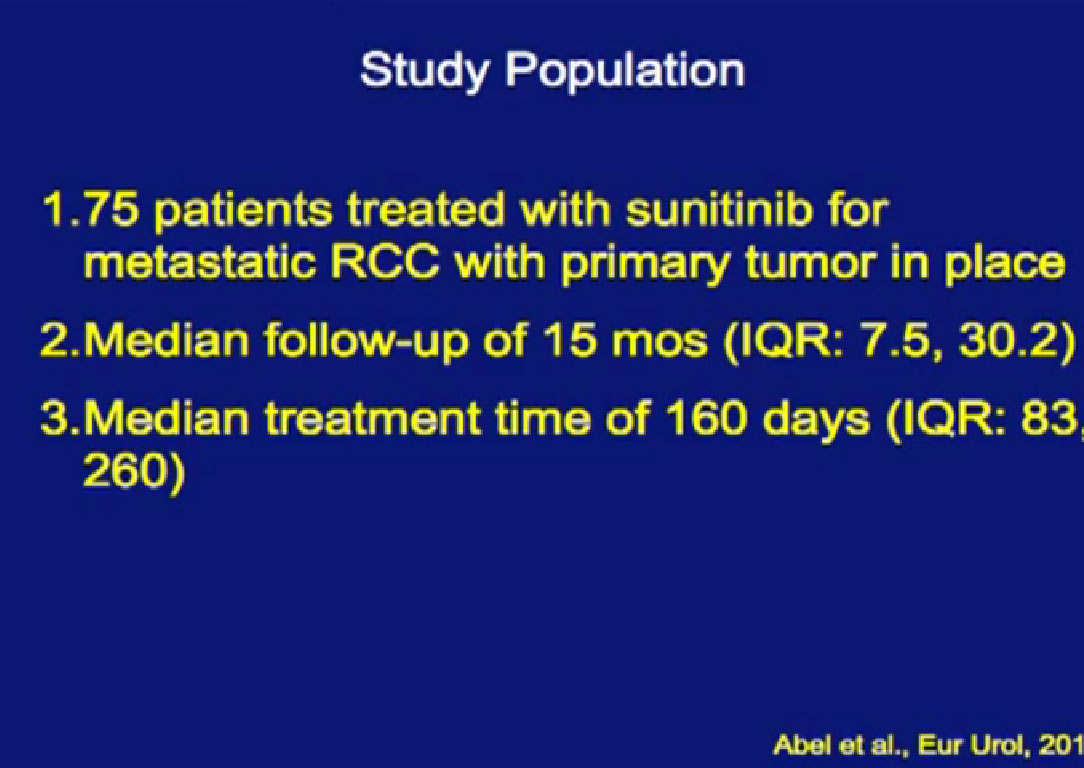

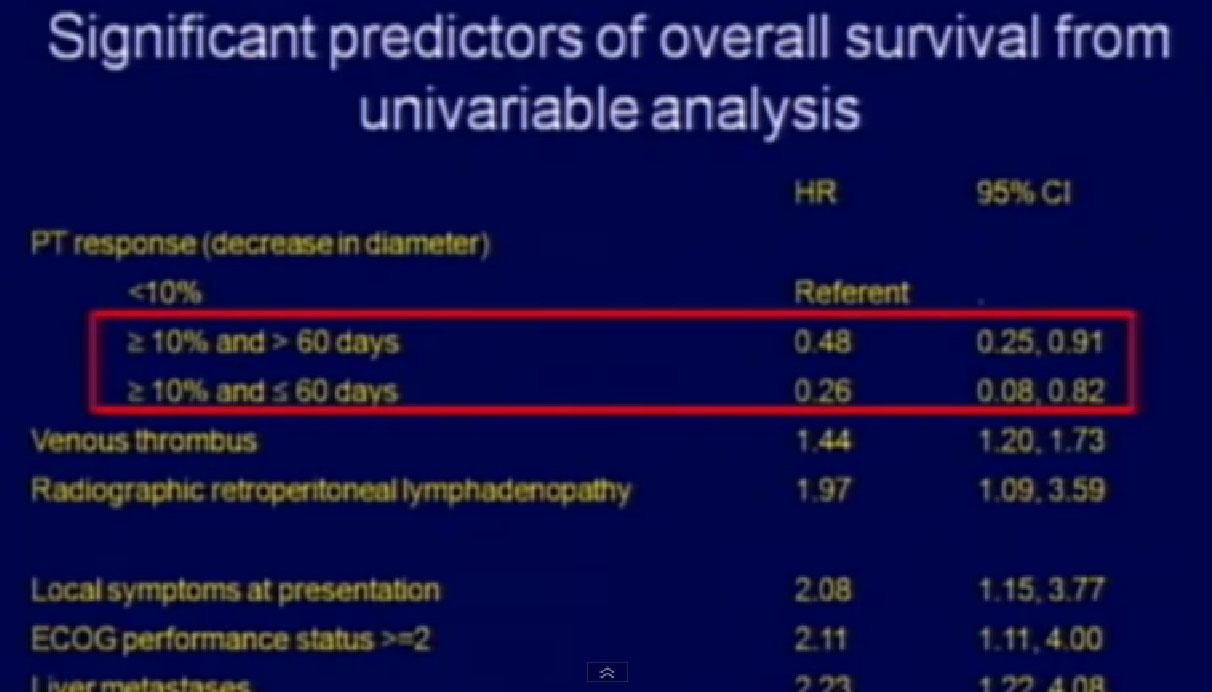

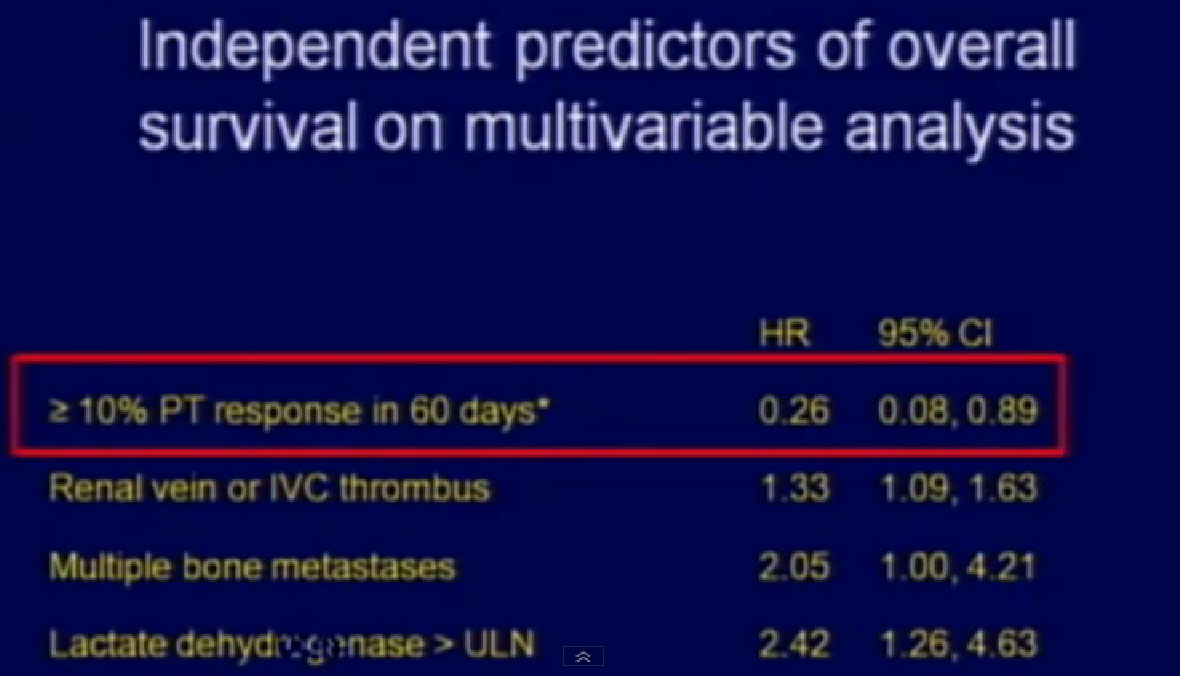

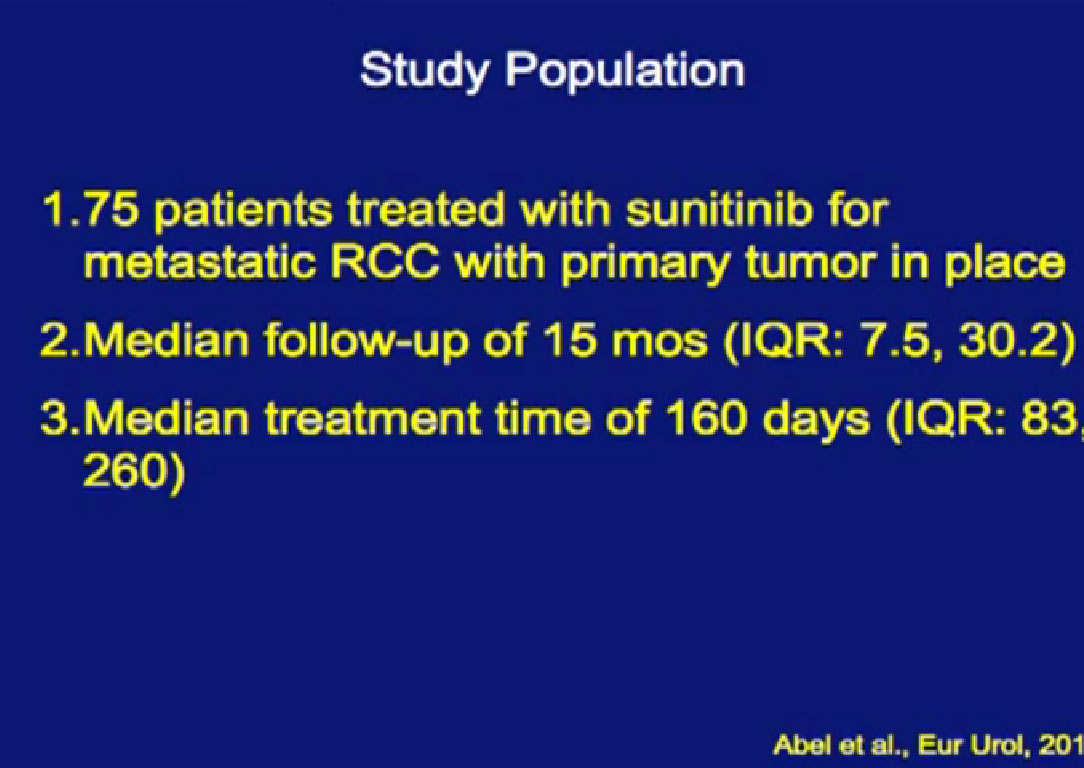

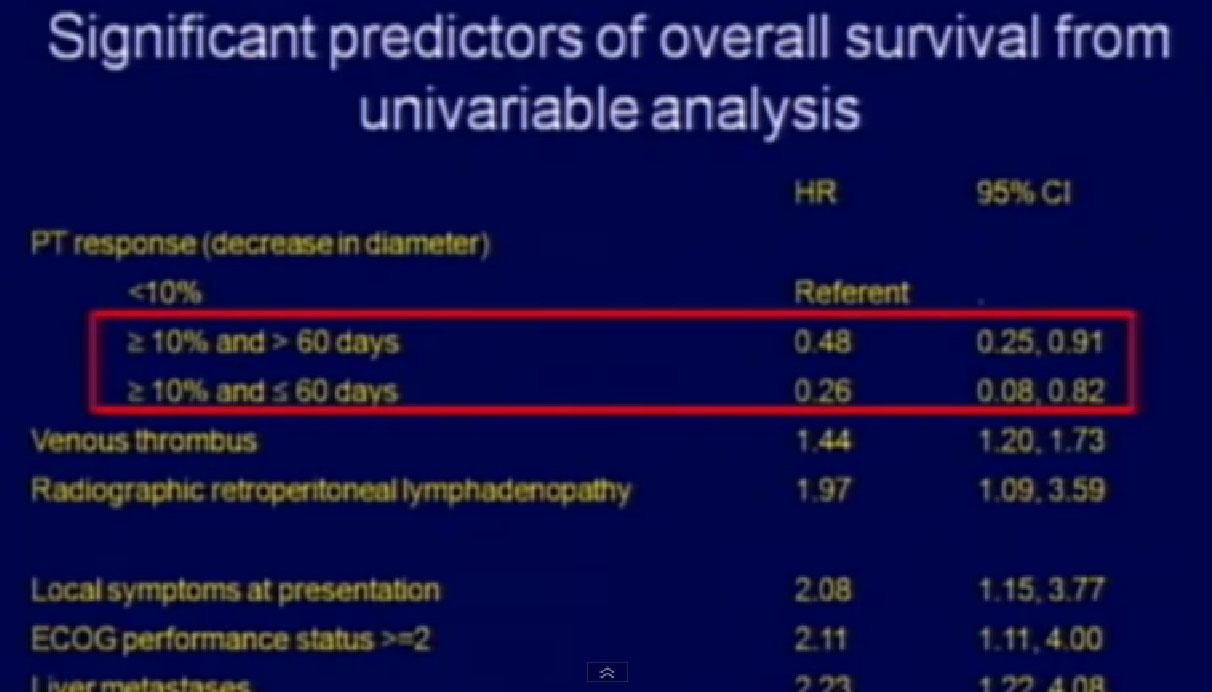

We treated 75 patients with Sunitinib with their primary tumor in place, and we found that those patients who had a greater than 10% response in their primary tumor had a significantly greater survival than those patients who did not have that early shrinkage of greater than 10%. If they had a greater than 10% response within 60 days, their survival was even better.

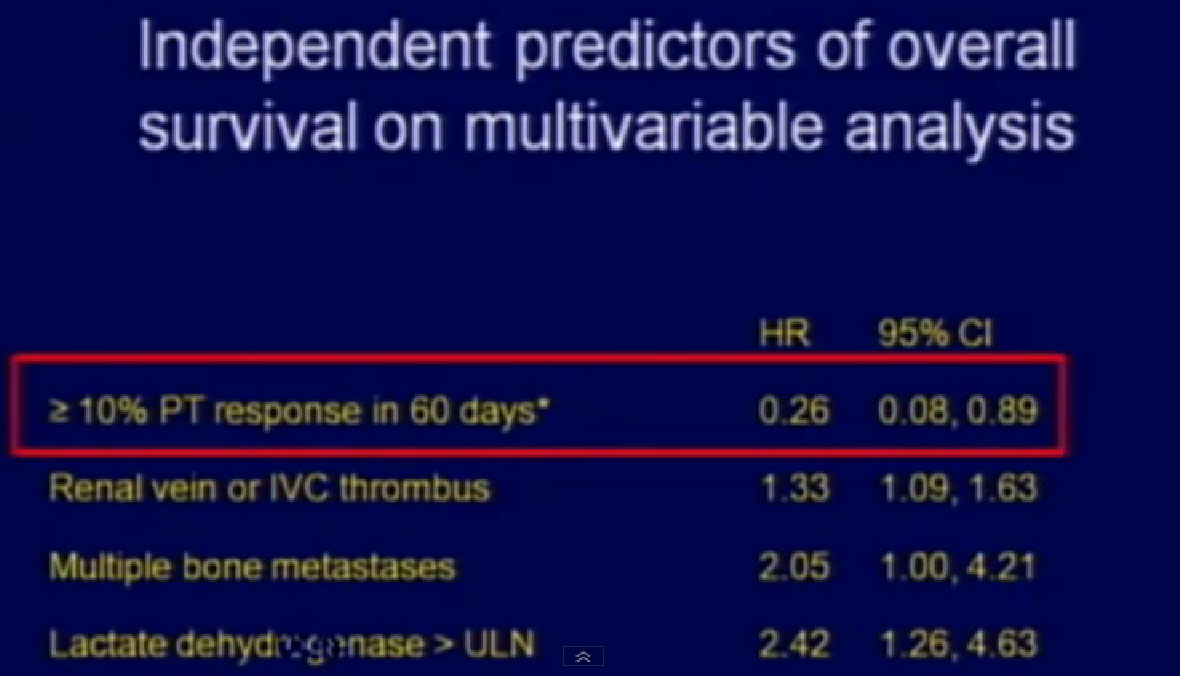

And that was in univariable analysis, and it also held up  in multivariable analysis.

in multivariable analysis.

For the first time, looking at the primary tumor’s response to targeted therapy could be used as a prognostic variable for outcome of patients.

In Europe, there was another study,  looking at Sunitinib. They arrived independently at the same conclusion that we did, that those patients (treated with their primary tumor in place) with a greater than 10% response in their primary tumor, when treated with their primary in place, had a significantly better outcome than those treated patients who did not.

looking at Sunitinib. They arrived independently at the same conclusion that we did, that those patients (treated with their primary tumor in place) with a greater than 10% response in their primary tumor, when treated with their primary in place, had a significantly better outcome than those treated patients who did not.

Cytoreductive Nephrectomy for Metastatic RCC in The Era of Targeted Therapy

Not a question of “IF” but “WHEN”?

I argue that cytoreductive nephrectomy is not a question of “if”, but really more a question of “When?”

58

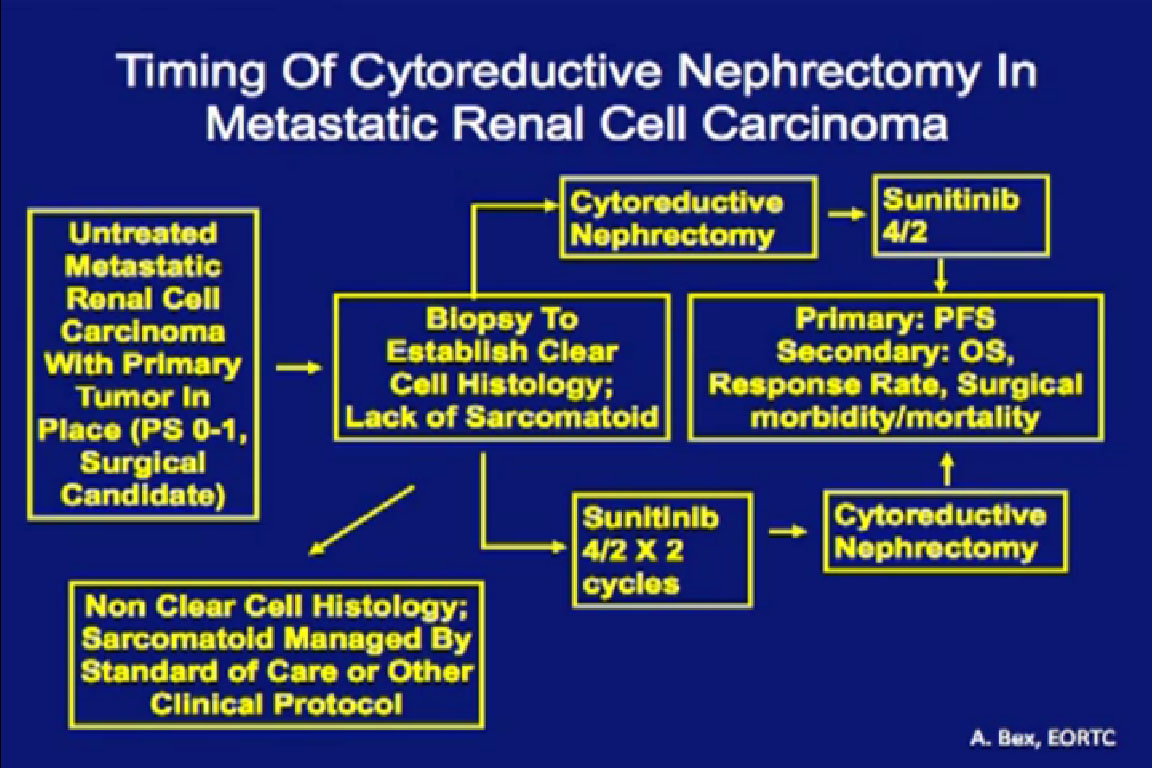

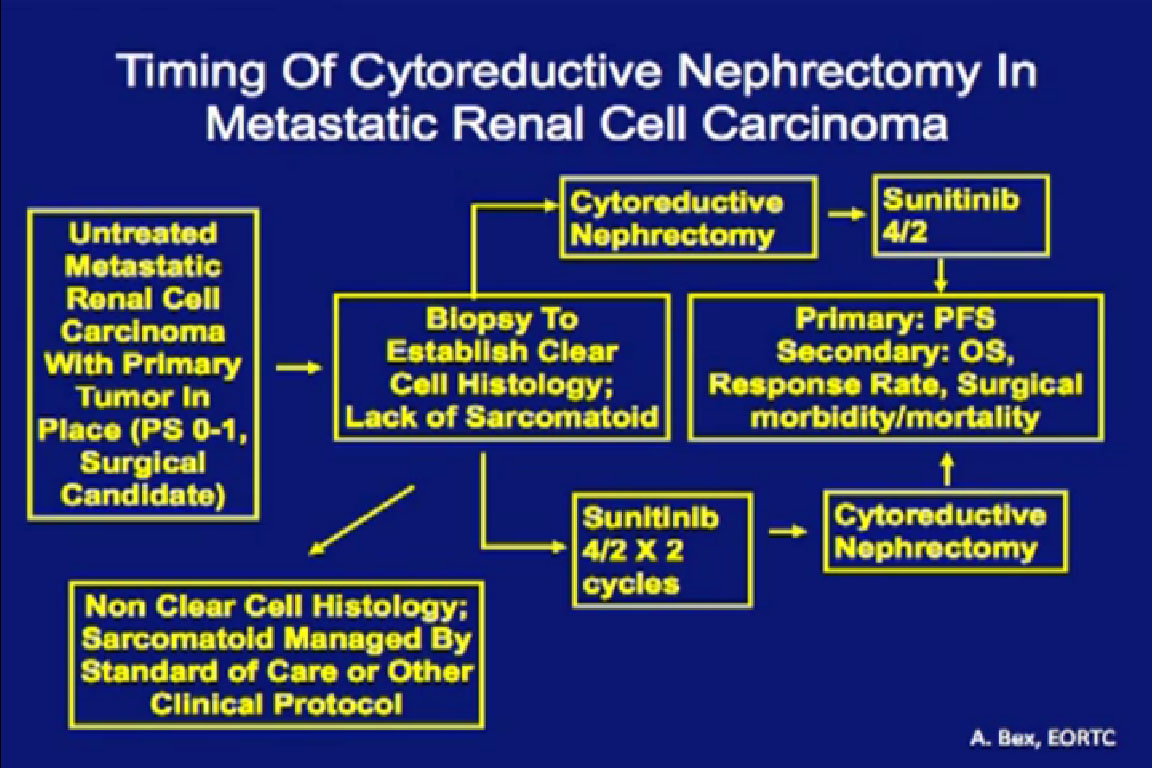

This trial that is currently ongoing in Europe through the ERTC, the CERTIME trial. Patients are randomized to cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by Sunitinib versus two course of Sunitinib followed by nephrectomy. This examines timing of the nephrectomy, not whether we should be doing a nephrectomy. This is a much more relevant research question, and this trial is accruing quite nicely over there.

In conclusion, targeted therapy has dramatically improved the outcomes for patients with metastatic RCC. Efficacy in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting still is under investigation. Without complete responses from this targeted therapy, surgery will remain an integral part of a multi-disciplinary approach, both as to control of the primary tumor and as metastasectomy. Show me an agent that demonstrates reliable and complete response, I will be the first to argue that we need to reexamine the paradigm.

Do not think that pre-surgical therapy is the standard of care. It is not. It has merit, but it needs further study and validation. It is not clear to me when it is appropriate to integrate surgery into the context of receiving systemic therapy. Thank you very much for your attention.

END OF LECTURE>

Questions and responses from audience.

Audience. “My question is regard to your last comment, as to the immediate impact of say, Sutent, showing up prior to surgery with an early response, does that also mean that Sutent–having a response in metastatic disease–does that tell you than an early response also means a generally better outcome?

Dr. Wood: I’ve got to tell you we haven’t looked at that, but that is a very worthwhile study to do. Intuitively, my answer would be yes, but I don’t think that we have anyone who has done a formal study on that. It is a very good question.

Audience: “How should ablation and the small tumors be monitored if you have those small tumors like less than 3 cm, like if you are a tumor producer, if you have “multi-foci” tumors?”

Dr. Kamar: Do you mean after or before the ablation?

Audience: “Before the ablation.”

Dr. Kamar: While you are on active surveillance?

Audience: “Yes, and if you have multiple primary tumors less than 3 cm.”

Dr. Kamar: This is more common in patients who have VHL syndrome, which is a syndrome where patients have a tendency to have more than one tumor in their kidneys. The follow up is every six months or so, so we don’t really want to image too often for the radiation risks that are involved with doing too many CT scans. Initially every 3-6 months and after the first year, move to every six months or one year. It also depends on whether the patient is young and healthy and why would we want to observe. In VHL patients that is done commonly, because we wait for the tumors to become 3 centimeters before we intervene. We don’t want to do surgery when the tumors are only 1-2cm in that particular patient population.

Wood; The 3cm we are talking about comes from the NCI where they have a huge experience in treating genetic kidney cancer, and they noted that patients with tumors 3cm or less never metastasize. So we use that 3cm size as a sort of trigger to tell us when we need to do surgery. With multi-foci disease, once it hits that 3 cm size, we will go in and debulk the tumors from the kidney, take all the tumors we can take out, and then follow them over time.

Audience: “I have a question re ablation. Is that an option if you have metastasized to your lungs?”

Dr. Kamar: You mean to use it on the lung tumor? (Yes) Do you mean on the mets or do you mean on the tumor in the kidney.

Audience: “No, my kidney is gone, but I have metastasized to the lung, and I have had cyberknife, but is it an option to be used on the lungs.”

Dr. Kamar: I think it is an option, but typically, if it is doable by surgery, which is the preferred way. The ablations that are done outside the kidney are mostly done for bone lesions, where cyroablation of RFA is done, because it is typically harder to remove a lesion from the bone than it is from the lung, for example. It is more commonly done for liver metastases if anything

Wood: It is more common to use it to treat symptomatic metastases, but there is some interesting work going on here at MD Anderson by one of our colleagues, where there may be some immunologic phenomena associated with ablation. We have some case studies that have been done, where patients who have undergone ablation, particularly RFA, not so much Cryo and had a complete regression of their metastatic disease, almost like a vaccine had been put on the met, and actually Seren is studying that with alone and with some of the immunologic agents that you will hear about from Dr. McDermott to see if that may be a viable treatment option for patients with kidney cancer in the future.

Audience: “After ablation, do you usually see necrosis in the body of the tumor? Can you see that during imaging?”

Kamar: You can see that afterwards, and typically more common with cyro. You see necrosis, coagulative necrosis. Typically it is coagulative to the tumor. You see that on the pathology, when you end up removing that tumor later on. So what we see is absence of contrast enhancement. The tumor before treatment was lighting up when you give contrast. After the procedure, it stays dark. That is our best indicator, other than biopsy, that the tumor is really treated by radio frequency. We don’t see really necrosis on imaging quite like for larger tumors like Dr. Woods showed earlier.

Audience: “So during subsequent imaging, you might see necrosis?”

Kamar: You might but typically what we look for is absence of enhancement. Necrosis is not something we reliably see or depend upon for follow up.

Audience: “For Dr. Wood, re venous thrombosis, do you insert an IVC filter prior to surgery, I’ve heard, or do you consult with cardiology to get that done. Is that helpful?”

Wood: Definitely that is not helpful before surgery. We have both had patients where some guy on the outside decided it would be helpful to put a filter in the vena cava, just in case a piece of the tumor thrombi broke off. It made surgery extremely, much more difficult. After the thrombus has been removed, in some patients we will leave a vena cava filter, which is like a screen put in the vena cave, so that blood clots below that screen blocks them from going to the lungs. A large pulmonary embolism could be fatal. So patients who do have evidence of a clot down in their legs, we will put a filter in, but if they don’t have any evidence of that, typically we don’t.

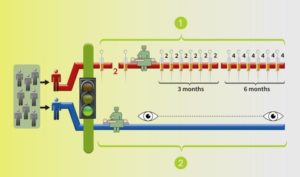

Two arms/groups: BLUE arm with surgery and monitoring by the trial team, the standard of care; the RED arm with medication before to surgery, followed by more after the surgery.

Two arms/groups: BLUE arm with surgery and monitoring by the trial team, the standard of care; the RED arm with medication before to surgery, followed by more after the surgery.

Me,

Me,