Kidney cancer patients are stunned by their diagnosis, anxious to make a treatment decision, and simply not know what to expect. If you are struggling with the issue of surgery to remove the tumor/kidney or to start with a med, you need to read this. Deb Maskens, Kidney Cancer Patient and Patient Advocate, our guest writer is a valued member of our disease community and currently serves on the Renal Task Force for the National Cancer Institute. A series of links below will also be helpful. (My extra comments will be in italics, like this. )Welcome aboard, Deb!

Clinical Trial Opportunity for Newly Diagnosed (Non Metastatic) Kidney Cancer

As a community of kidney cancer patients, we hear from newly diagnosed patients looking for treatment options. This is written for those patients, and for patient advocates who help patients navigate through their treatment decisions.

The challenge: this clinical trial is available at many locations across the U.S. and Canada, but patients must ask about it BEFORE they have a nephrectomy. Their own doctors may be unaware of the trial and how to work with the trial centres. In many places, patients get booked for surgery prior to learning about this option. That would be too late for a trial like this–it gives a drug therapy before the surgery for a brief period. (In one of the t wo arms, there is medication before the surgery.)

Why Might Patients Consider this Trial?

For years, the standard of care for early stage kidney cancer has been to remove the tumour surgically, sometimes with the entire kidney–either a partial or full nephrectomy. That was the end of treatment and the beginning of surveillance to watch for any signs of recurrence. (And early stage tumors can be quite large–up to 7cm or about 2 3/4″.)

Now we hope to prevent a recurrence of disease. Since advanced or metastatic kidney cancer is still incurable for the vast majority of patients, this is a worthy goal. With preventive or ‘adjuvant’ treatments, maybe we can stop the disease before it gets to the lungs, liver, bones — to those places where it begins to threaten our lives. Other cancers use this approach and offer patients a real chance to avoid recurrence.

Adjuvant – and Perhaps One Step Better to Neo-Adjuvant

We’ve seen trials for “Adjuvant” (or preventative) therapy which hope to prevent recurrence (treatments given immediately after nephrectomy). But one trial goes one step better – it’s for “Neo-Adjuvant” (before nephrectomy) as well as Adjuvant (after).

Patients may want to rush to surgery to “get it out”. In reality, those tumours have generally been growing slowly, undetected for many years. Kidney cancer surgery is rarely an emergency. There is usually time for a second opinion and to check out any newer approaches.

Here’s the thought: given that the tumour cells have gone undetected and tolerated by the immune system for so long, can put those millions of cells to work and make them “show their calling cards” to our immune system before we take them out?

Combining Neo-Adjuvant and Adjuvant Treatment – PROSPER-RCC

The Phase 3 clinical trial called PROSPER-RCC (NCT03055013) is for patients whose tumors are 7cm (2 ¾”) and larger in size, but not spread beyond the kidney area. These patients are at greater risk of spread of the cancer than those with Stage I or with smaller tumors.

Based on earlier studies, nivolumab (Optivo) is now approved for advanced kidney cancer. This is a trial to test whether there is a benefit when nivolumab is given immediately before and after a nephrectomy when tumor cells might have spread outside the kidney but are too small (microscopic) to see on scans. (Typically a patient without spread of disease would not be treated, but monitored.)

The Rationale for PROSPER-RCC: Why It Might Be Helpful

Here’s what I’ve learned:

- Checkpoint inhibitor treatments with PD-1 blocking drugs like nivolumab seem to work best when the immune system may be being turned off by this cellular growth pathway. Cancer is deceptively clever and some tumours can express a protein, PD-L1. This protein can turn off our immune cell responses that recognize and fight the cancer. There was a hint of this with some positive data that indicates that these drugs work best in patients whose tumors were “PD-L1 positive”. (PD means Programmed Death and PD-L Programmed Death Ligand or connector. Death to the cells, and the signalling loop that hinders the immune response.)

- In theory, when the kidney tumour is in place, there are millions of cancer cells. All of those tumour cells send off multiple negative signals to the immune system to stop it from working. However, if a checkpoint inhibitor was used and stopped those blocking signals, the immune system would have a big wake-up call – e.g., lots of targets with which to build an army of T cells. In theory, these newly educated T cells would later turn into memory cells. (If the body can maintain these memory cells, they would continue to fight any return of disease.)This is much like what happens when we are exposed to certain bacteria or viruses. Once we get exposed to the bug, we don’t usually get it again. Our immune cells have learned (“immunity”) how to kill it more quickly the next time before it turns into a full blown cold. Similarly, if these anti-RCC immune cells ever see one of these tumor cells anywhere in our bodies again, they would know to attack and kill them even if there is no drug in the patient and has not been for some time.

- Surgery is still the main treatment to control early stage kidney cancer. But it will also remove the majority of targets (PD-L1) that the checkpoint drug uses to rev up the immune system. Giving the checkpoint inhibitor before surgery may maximize/optimize the drug’s ability to wake up the immune system and build that T cell army.

- So the surgery is important. But let’s assume a few cells might be still circulating and have gone undetected for some time. They could still show up later on a scan as an enlarged lymph node or spot somewhere. A boost of the same checkpoint inhibitor right after the surgery could then be used to remind the immune system to continue to look for those cells and kill/eliminate them when they are small. In theory, the immune system will remember what the past “trouble” was: “Hey, haven’t I seen you before?”

From what I understand, this theory worked well in mice. The checkpoint inhibitors worked better if the primary tumour was there to help provide “a target” to activate the immune system first before the tumor was removed. While we’re not mice, this makes sense, no?

Trial Design: What Really Happens to the Patient in the Trial

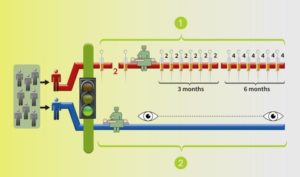

PROSPER-RCC will place patients randomly into two groups:

- Group One gets two infusions of nivolumab before surgery (at about 28 days and 14 days before surgery). Following that nephrectomy, the patient will receive more infusions of nivolumab. This is for 9 months post-surgery altogether, with 12 more doses.

- Group Two gets the usual standard of care: upfront nephrectomy, partial or radical nephrectomy, and will be followed by close observation at an expert centre.

Two arms/groups: BLUE arm with surgery and monitoring by the trial team, the standard of care; the RED arm with medication before to surgery, followed by more after the surgery.

Two arms/groups: BLUE arm with surgery and monitoring by the trial team, the standard of care; the RED arm with medication before to surgery, followed by more after the surgery.

It is important to note that no patient on this trial receives any intravenous placebo/inactive treatment. Every patient is treated. Each patient will have either the experimental treatment or the standard of care. All are under close observation at the trial centre. This trial has been designed and discussed with patient advocates and is supported by the NCI.

For More Information

Patient-friendly explanation here – http://www.10forio.info/clinical-trials/prosper-rcc

For contact information at over 100 trial sites, dig a bit in the site below:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03055013

or call the office of the Principal Investigator, Dr. Lauren Harshman, at: 617-632-2429

Deb’s Disclaimer:

As a patient and advocate for kidney cancer patients, I have been delving into the world of clinical trials and trying to understand as much as I can. I’m not a scientist, but I am a patient with this disease, so I bring that lens, along with some abilities to translate science into understandable terms. As a volunteer, I have no financial interest in this trial or any specific medications. @DebMaskensKCC; dmaskens@rogers.com