The headlines announced (or pounced upon) a study from ASCO (American Society Clinical Oncologists), with MedScape’s 6/2/2018 example: “In Advanced Kidney Cancer, Surgery No Longer Sole Standard of Care”.

Is there value to surgery in advance of treatment with Sutent(sunitinib) for the patient with metastatic clear cell carcinoma? The study author, Dr. Arnaud Mejean from France claimed, “Cytoreductive nephrectomy should no longer be consider the standard of care in metastatic renal cell carcinoma.” My own doctor said it, “flips the existing paradigm” of treatment. Typically, a patient with metastatic kidney cancer has a nephrectomy, likely followed by medications or even more surgery to remove metastases.

What the heck does this mean to patients? How will the less-experienced urologists and oncologists interpret this? Is there a comparison with treatments in the US to used in this trial? What are the important DETAILS?

Stunned at headlines, I studied the original NEJM article. Since 425 of the 450 in the trial were from France, I tried to compare mRCC stats in France to the US stats as available. Should this study alter diagnosis and care of metastatic RCC patients? No trial never gives the whole picture, and quick headlines add confusion. Earlier studies have concluded that there is benefit to an upfront nephrectomy, even when there are metastases. Officially, that is a cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN)–removal of the affected kidney with mets in place.

This study says NOTHING about patients who have NO METASTASES, but do have malignant tumors. A tumor, large or small, can create metastases. Some doctors don’t look for metstases before or after the surgery, but they may still be there. The “Got it all” message is a comfort but is no guarantee that the cancer has not spread, or is not visible to the surgeon as he operates. Of course, mets may be found away from the site of the surgery, so an ‘all clear’ signal does not cover bones, liver, lungs, etc.

Note also that this is for clear cell kidney cancer patients only: there are other subtypes of RCC, so those cases were not permitted in this trial.

Trial patients can vary from ‘real world’ patients. Depending on the time to find the disease, they may be quite sick. They may be referred to a trial when their case is too difficult to manage locally, and perhaps after a lengthy delay as to the diagnosis. Usually they are seen by a general practitioner, eventually receive a CT scan, likely are referred to a urologist or oncologist. A urologist who might remove a large 8-10cm tumor (3-4 inches), but may not want to do for many causes. Thus it is important to understand the non-surgical options for those rarer cases. This is true in the US and well as France. Although 425 of the 450 patients were from France, there may be broad differences in general access to CTs and the referral pattern for these patients.

With more unanswered questions, this trial should NOT change the entire approach to a nephrectomies for mRCC patients.

Missing Data and Blocks of Patient Time to Treatment?

Time lost without care for cancer patients is lost opportunity for longer survival. This can be common: the patient has a complaint–anemia, cough, blood in urine, pain in his flank, concern of a general sort of failing health. He may be examined and given blood tests, internal exams, etc and eventually a CT scan. He then may be referred to a specialist, even to get a referral for the CT scan. With the finding of a kidney mass, the patient may then see an oncologist or urologist. How long these patients were sick until there was a final diagnosis is unknown.

From the initial diagnosis and eventual recommendation to the CARMENA trial, the patient was without care. We do not know how long it was for the recommendation until the actual enrollment in the trial. To be enrolled, the patient must first have the recommendation to do so, be set up to see the trial physicians, and have a biopsy before enrollement can happen. With the large tumors found, such biopsies likely did not happen until referral to the trial. The trial accepted only clear cell RCC, thus the biopsy was necessary. We do not know if the biospies were reviewed by one central pathology lab, or if there were many opinions from various labs. Was it days, weeks or months from referral to biopsy to actual enrollment and randomization into one of the two arms of the trial.

These steps can delay treatment, adding weeks or months from initial diagnosis until either surgery or Sutent. Remember that all these patients were definitely found with metastatic disease prior to trial recruitment

According to the trial, all the enrolled patients were in intermediate or poor risk categories. Everyone had recognized risk factors. The ECOG performance status (PS) of 0-1, so able to care for themselves, not bed-ridden. That means that they could function fairly normally. In the Surgery First group, about 70% of the patients had tumor Stages 3 & 4. Only 50% of the Sutent Alone group with in Stages 3 & 4. As to the tumors themselves? The aggressiveness of the tumors were also measured from the biopsies, with about half having more aggressive disease at Furhman grade 3 and 4.

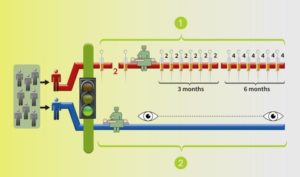

The trial protocol indicates that the surgery first patients do so within 28 days. Though the median time to to so was 19 days. However, some obviously had surgery much later, up to 50 days post randomization. It would have been valuable to know if delay of surgery played a role in outcome.

We are not told where the patients had surgery. This is important, as there is clear survival advantage to patients who have that surgery at a “High Volume” institution.

The patients randomized to “Sutent Alone” group also had the initial diagnosis, and were sent to the trial site, which may have delayed their treatment. Medication was to start within 21 days of randomization, which seemed to have happened in a timely manner. They got the 4weeks on/2 weeks off regimen, which is the standard of care. Again, no sense of how quickly they were into treatment post diagnosis.

Back to the “surgery-first, then medication” group: their Sutent treatment was to begin 3 to 6 weeks post surgery. (Some doctors would not do a nephrectomy that quickly, as Sutent can interfere with healing post-surgery. )

By final randomization, there are 226 Surgery First, then Sutent patients, and 224 Sutent Alone patients. But of the 226 surgery patient 40 did not receive Sutent, so down to 186 patients, which was furthered diminished by 20 patients. Post their surgery & Sutent time, 114 received ‘futher lines of therapy’.

In the Sutent alone group of 224 patients, 11 did not get Sutent, leaving 213. Of those patients 38 (17%) did undergo nephrectomy due to ”control of symptoms”, and at about 11 months after randomization. After leaving Sutent for reasons of toxicity and/or disease progression, 115 received additional therapies.

Questions Unanswered

How sick were these patients, how big were their tumors, where else did they have metastases? The stats between the two group are pretty similar, in most factors. But I note that the primary tumor sizes, although matched, are generally big. The median is 8.8 centimeters. Bad enough, but the measure of ‘tumor burden’, which includes metastases, generally in two groups is pretty stunning. That is described as 14cm, with sizes up to 39.9cm in the Surgery First group, and 31cm in the Sutent Alone. With the large percentage (70%) of Stage 3 & 4 patients in the surgery group, the range of sizes of tumors was considerally greater–up to 33.9cm. Only 50% of the Sutent only group were in Stage 3 & 4, with the maximum tumor burden about 31cm. One could argue tha the groups were not well-balanced as to the level disease found in the separate groups.

Despite what appears to me to be high tumor burden of both primary and metastatic disease, the authors claim that patients with either “a poor performance status, minimal primary tumor burden and high volumes of metastatic disease” are “not generally recommended to undergo a nephrectomy”. This is apparently the general standard of care in the participating institutions. This seems contradictory to me! There is no clarity here. If ‘minimal primary tumor” means a 1-3cm tumor, that is understandable, but the 4-8cm tumor would seem to be the typical nephrectomy patient. The issue of no nephrectomy for patients with ‘high volumes of metastatic disease’ seems to describe the patients in this study very accurately. Or does the French experience of RCC patients vary so much from the US experience?

How well did they tolerate Sutent? Of the surgery first group, over 30% had dose reductions, and in the Sutent alone group, it was quite similar–all done to manage adverse events. Grade 3 or 4 events–really tough kind–were more common in the Sutent only group, with 43% reported thus, and 33% in the surgery/Sutent group.

- The ratio of deaths from RCC patients in France compared to those diagnosed in year 2013 is about 1 in 3. The same ratio in the US is about 1 in 5. Rough stats, but that makes me wonder if getting a cancer diagnosed sooner and treated sooner might have something to do with that. These trial details make me question whether the typical French patient is diagnosed and begins treatment early enough to make a difference in outcomes.

Happy to share my documents and would love to hear comments/complaints, esp from the EU and UK people who may have a different view.