Dr. Eric Jonasch of MD Anderson Cancer Center gave the following talk at a KCA patient conference in April 2012. “Systemic Targeted Therapies” include a group of drugs, all approved by the FDA in . the last six years. These drugs mark a critical breakthrough in providing more options for kidney cancer patients, and their use and complete integration into treatment is still ongoing.

(Where good slides were available, they were used; those which were hard to read have been recreated.)

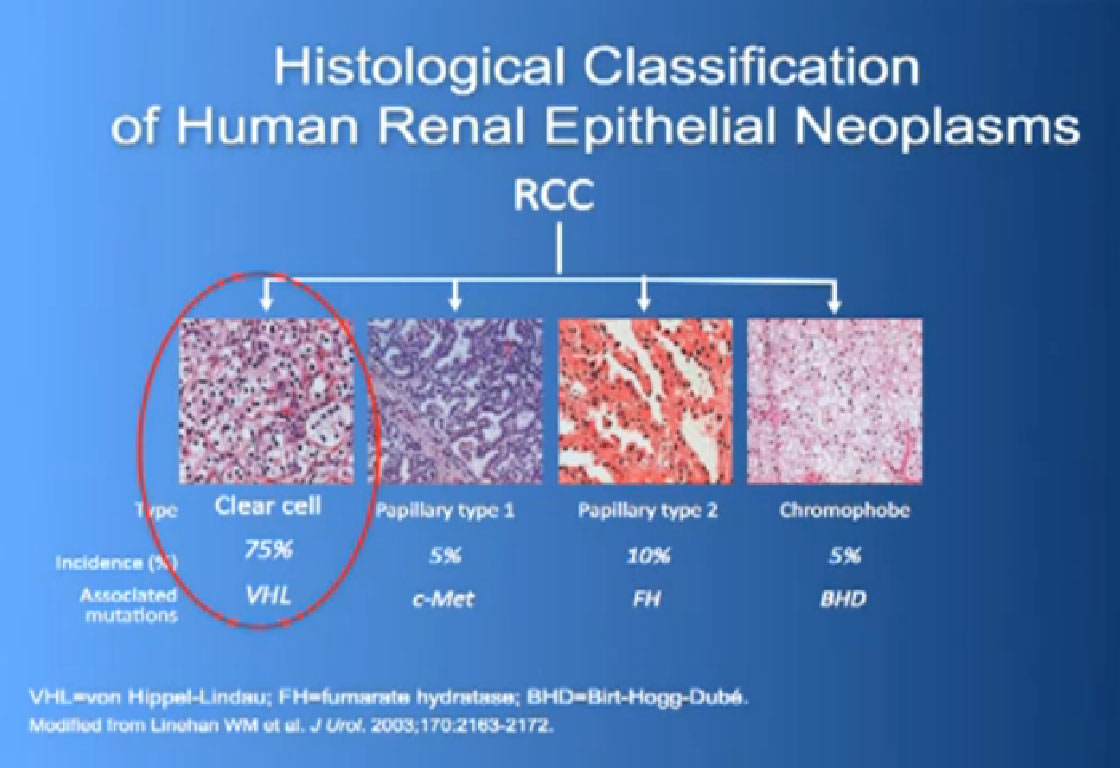

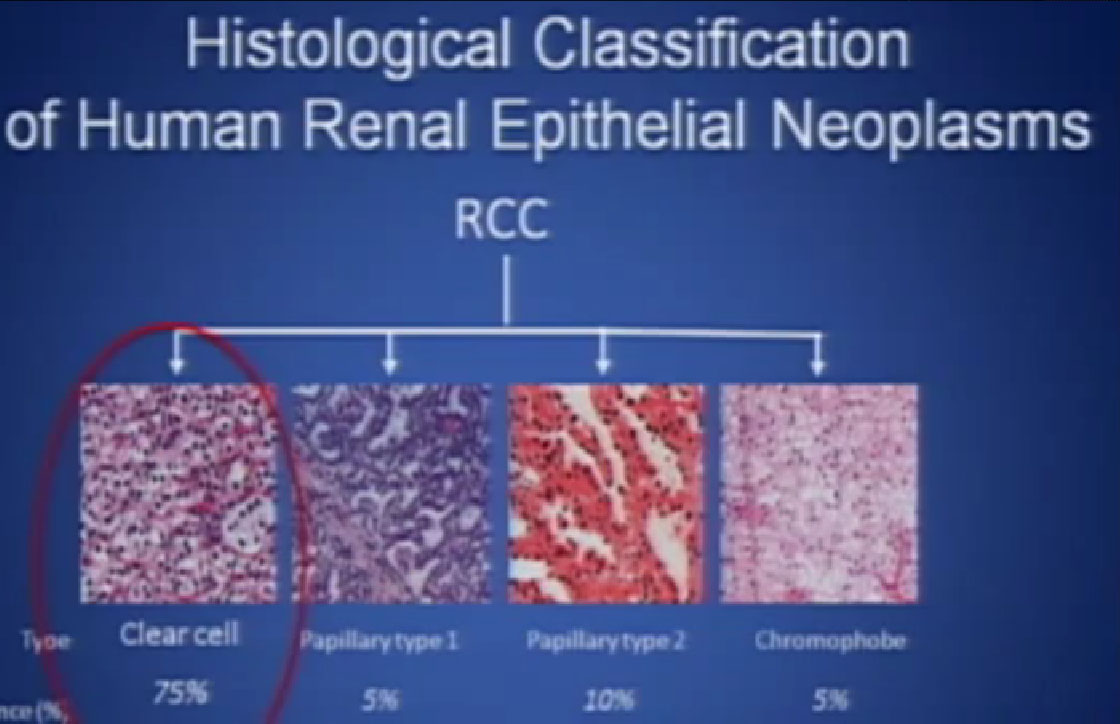

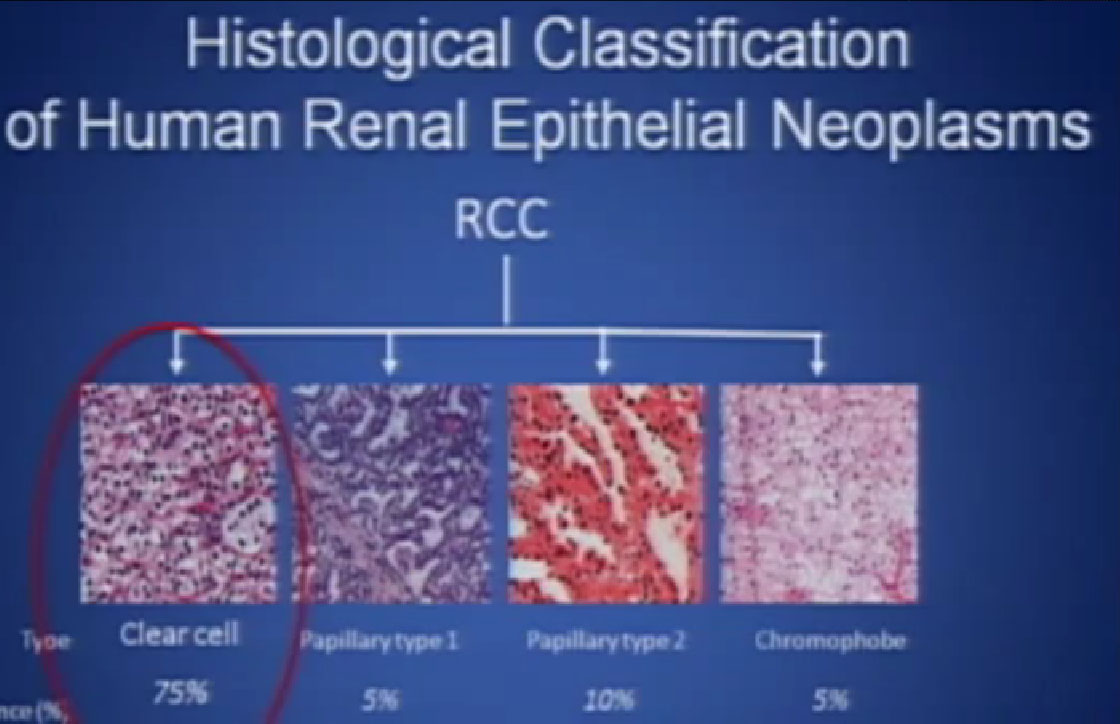

I am going to talk as systemic targeted therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer, how we are using it, and the science about it, and how that leads us to new ideas, moving forward. When we talk about kidney cancer, we cannot talk about just one disease type. What I am going to talk about mainly is clear cell, and Dr. Tannir, my friend and colleague, is going to talk about the non-clear cell subtypes.

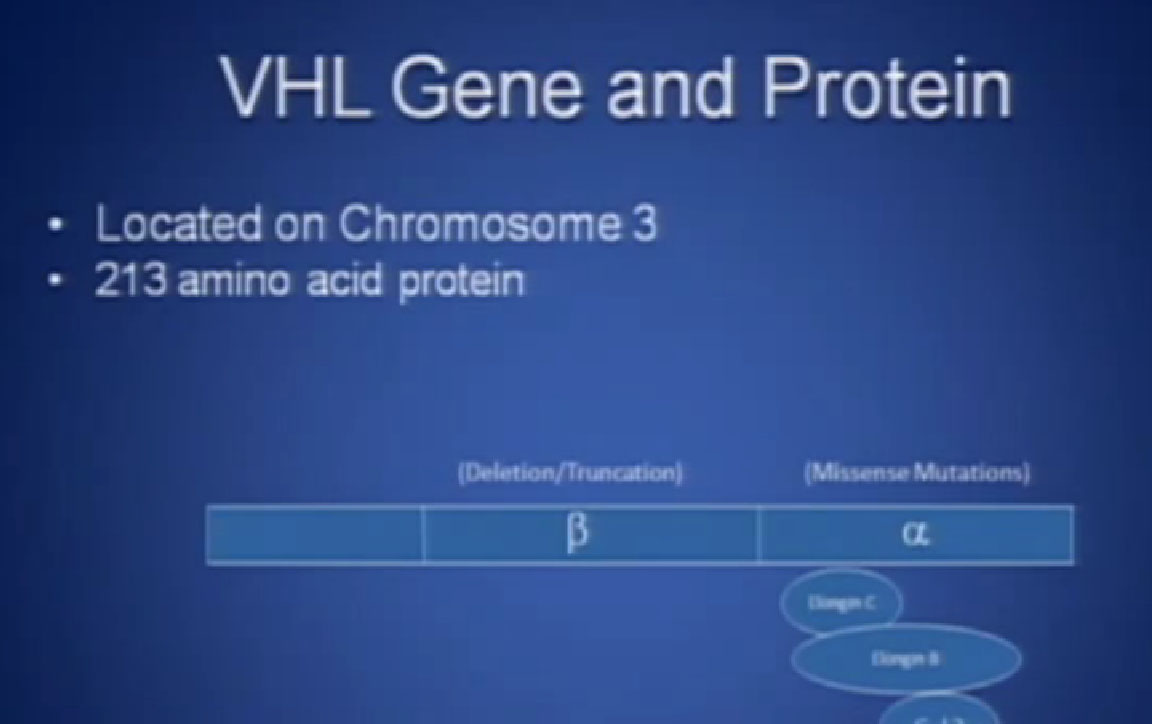

So what is ccRCC? It is essentially a cancer that looks like this under a microscope, and it was called this, back in the day. We more recently found that it has a mutation in the VHL gene (Von Hippel Lindau) in the vast majority of individuals with and I also run a clinic where I try to marry the information we have about hereditary kidney cancer with non-hereditary kidney cancer to improved therapies.

So what is ccRCC? It is essentially a cancer that looks like this under a microscope, and it was called this, back in the day. We more recently found that it has a mutation in the VHL gene (Von Hippel Lindau) in the vast majority of individuals with and I also run a clinic where I try to marry the information we have about hereditary kidney cancer with non-hereditary kidney cancer to improved therapies.

This is not to scale; it is 213 amino acids long and for the scientists in the audience, that is mercifully short, and it also has three exons in or three parts, or easier to study than most, but obviously still hard to study.

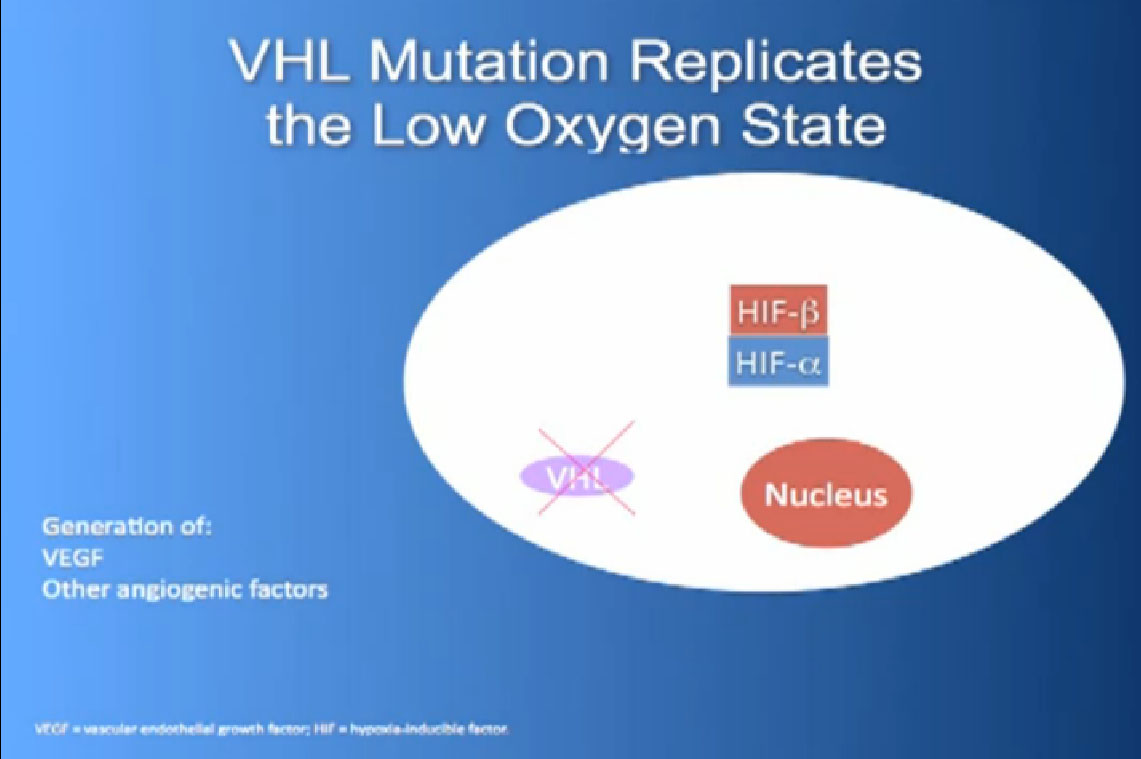

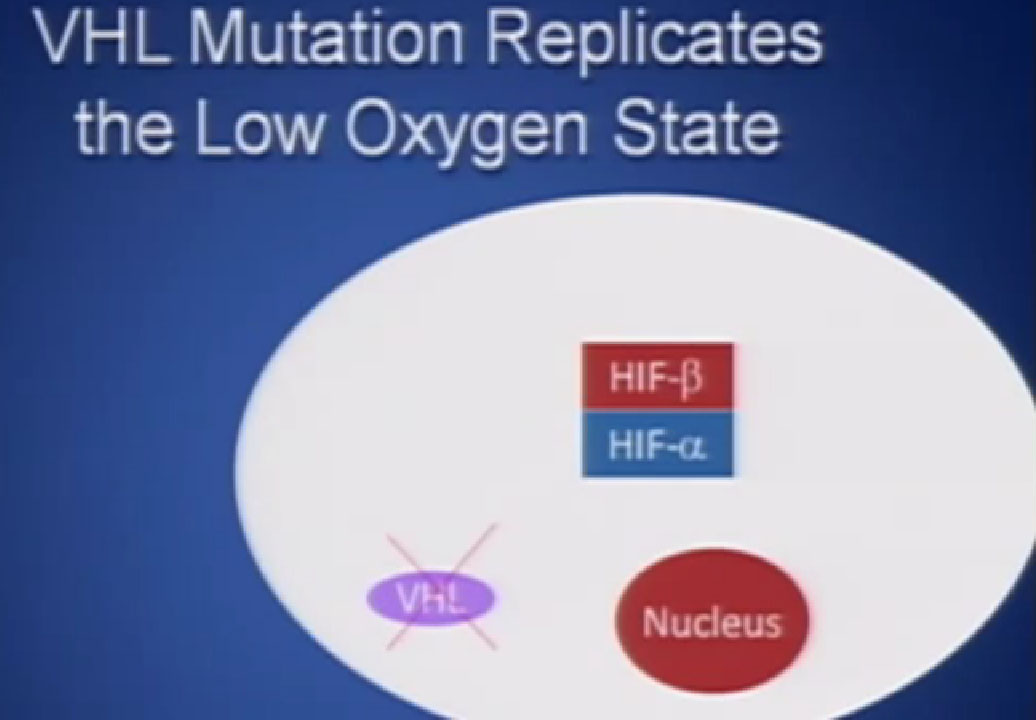

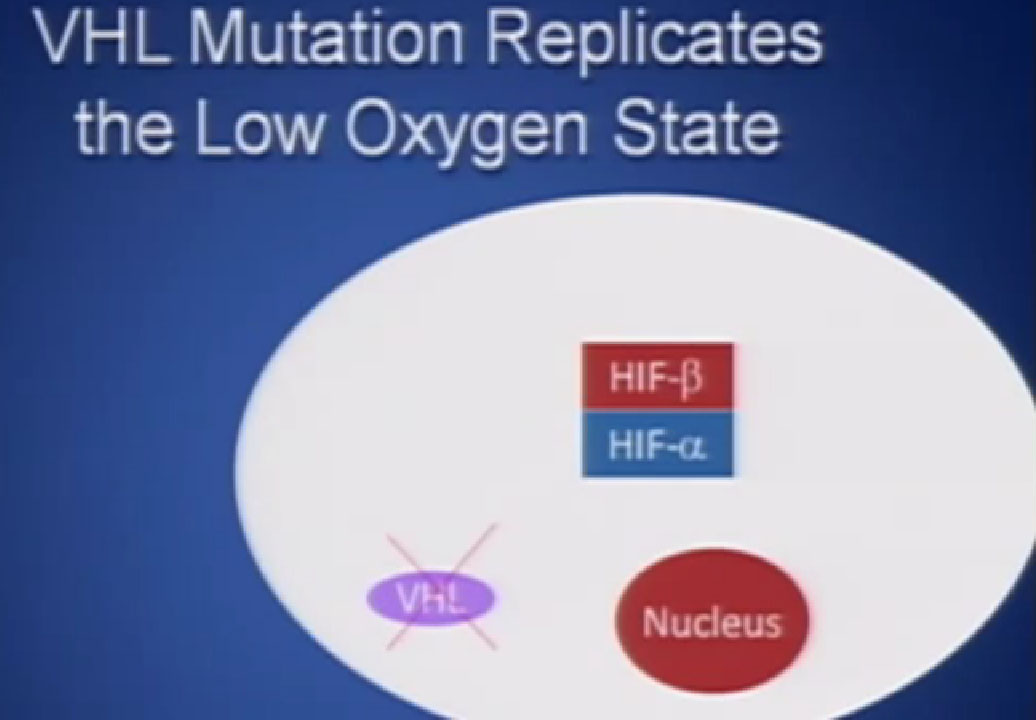

It essentially regulates how the cell reacts to oxygen. Obviously, oxygen is our life’s blood, we need oxygen, we need water, we need glucose. And our cells, if they feel like they need oxygen, they basically sit back and VHL will then take the transcription factor, which tells the cell which protein to generate, and then it breaks it down. If you have low oxygen state, then the cell will say, “Help, I need oxygen” and the VHL will step back, the transcription factors, HIF alpha and HIF beta are going to come together and you will get production of proteins, like VEGF which is a growth factor for blood vessels and some other things. If you have a mutation or something how an inactivation of the VHL gene, you have essentially an ongoing process of these cells, now cancerous, saying—somewhat untruthfully—we need more oxygen, we need more blood, build me an infrastructure.

It essentially regulates how the cell reacts to oxygen. Obviously, oxygen is our life’s blood, we need oxygen, we need water, we need glucose. And our cells, if they feel like they need oxygen, they basically sit back and VHL will then take the transcription factor, which tells the cell which protein to generate, and then it breaks it down. If you have low oxygen state, then the cell will say, “Help, I need oxygen” and the VHL will step back, the transcription factors, HIF alpha and HIF beta are going to come together and you will get production of proteins, like VEGF which is a growth factor for blood vessels and some other things. If you have a mutation or something how an inactivation of the VHL gene, you have essentially an ongoing process of these cells, now cancerous, saying—somewhat untruthfully—we need more oxygen, we need more blood, build me an infrastructure.

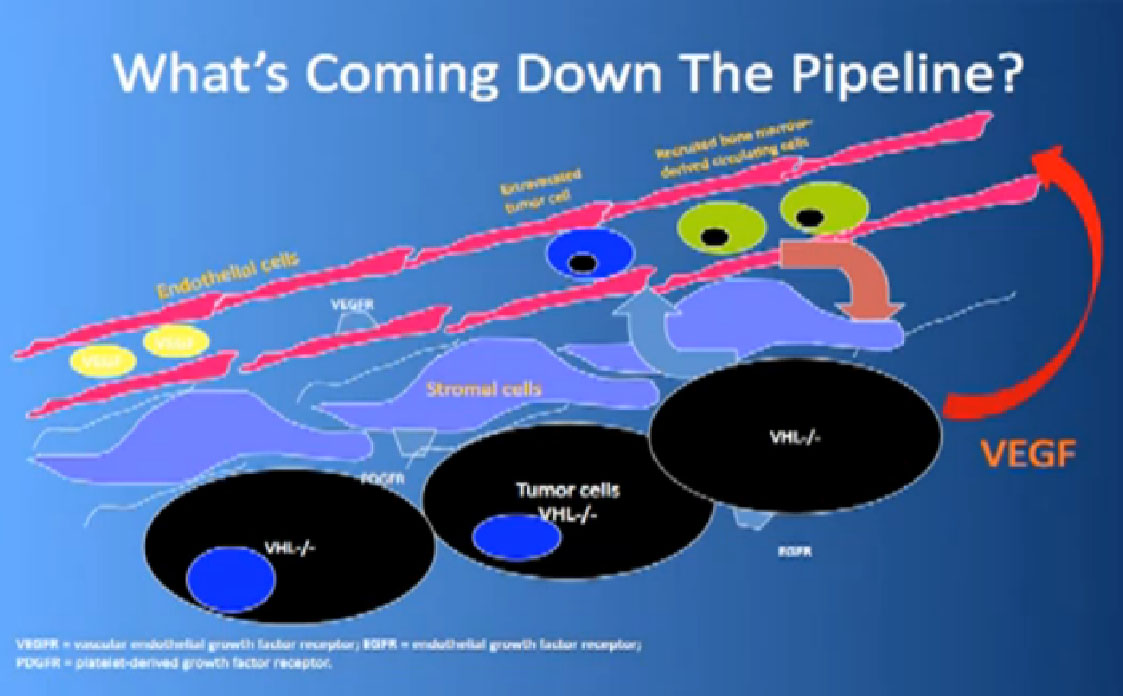

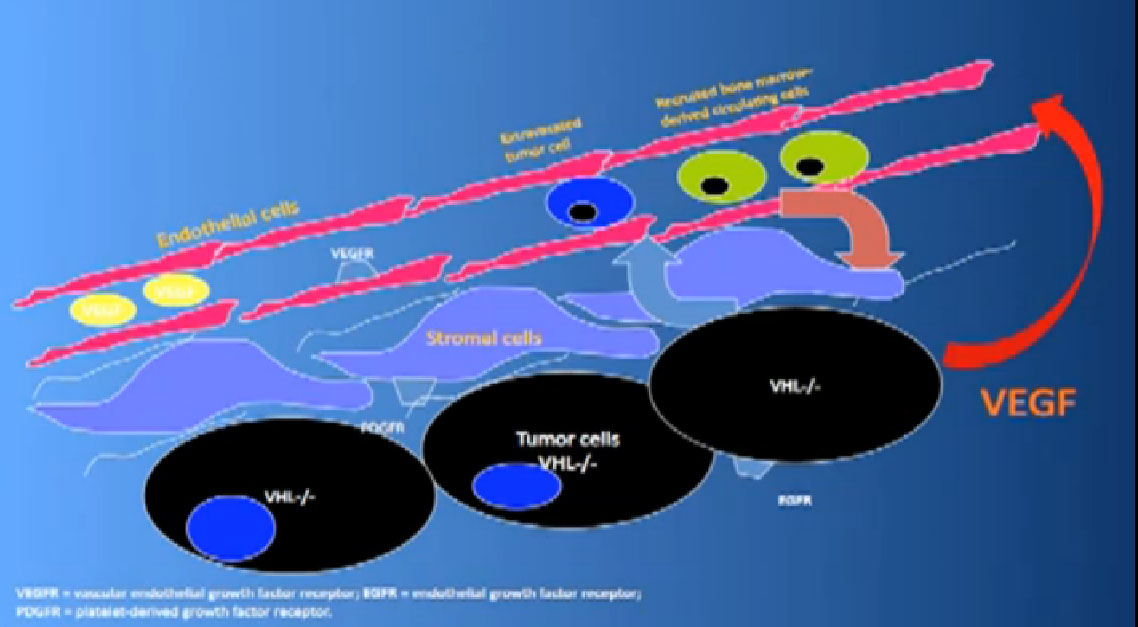

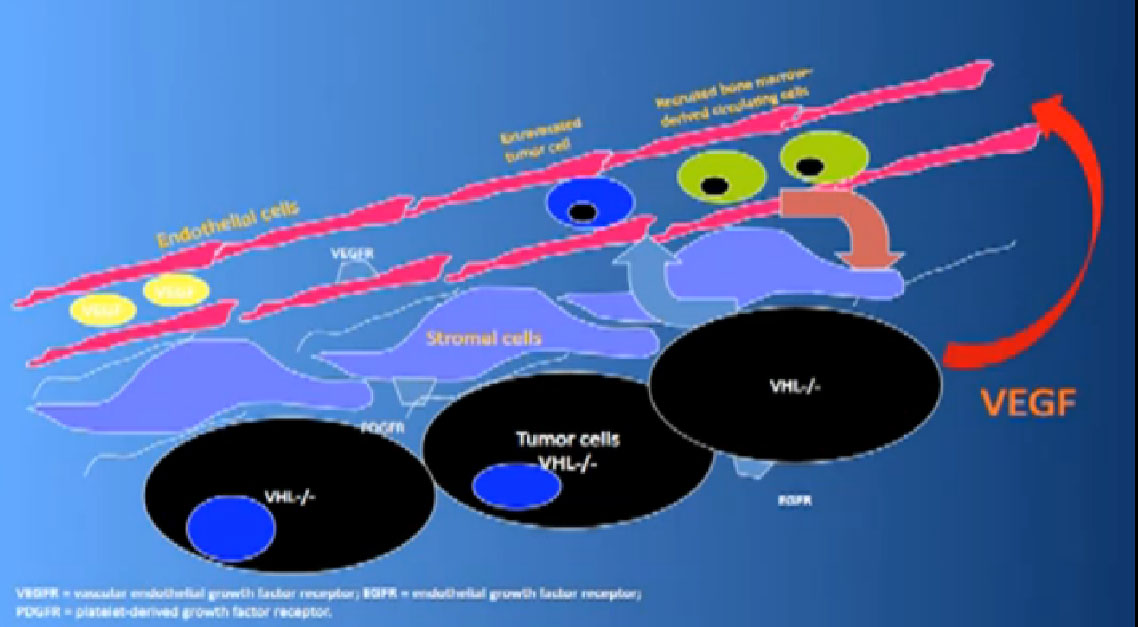

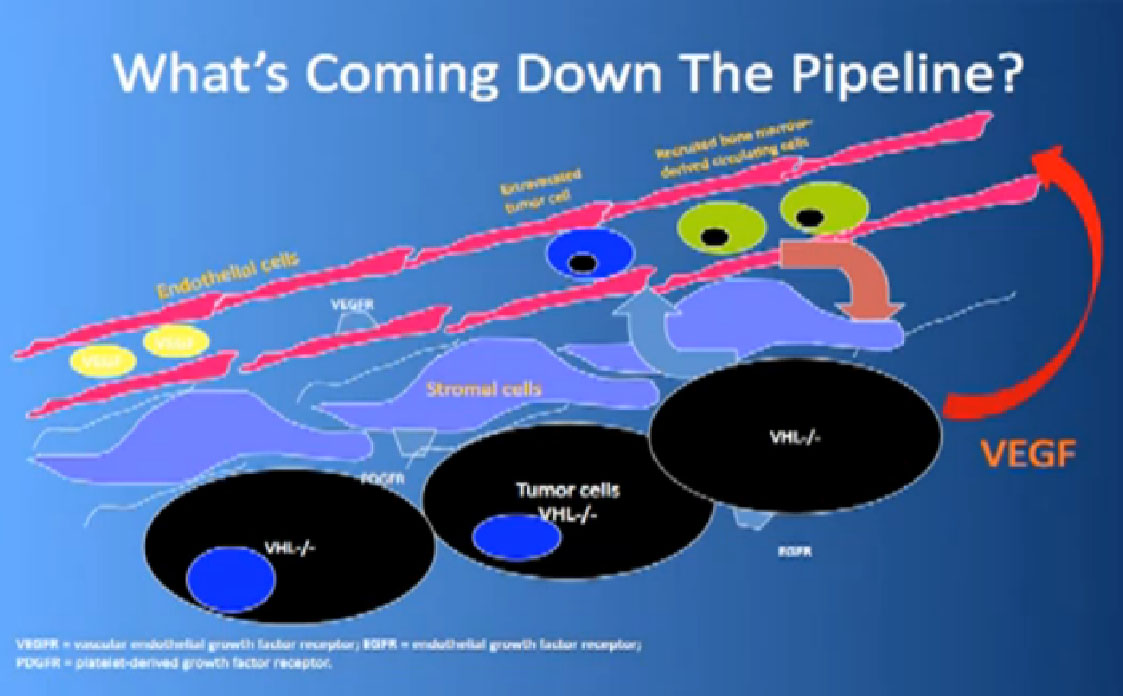

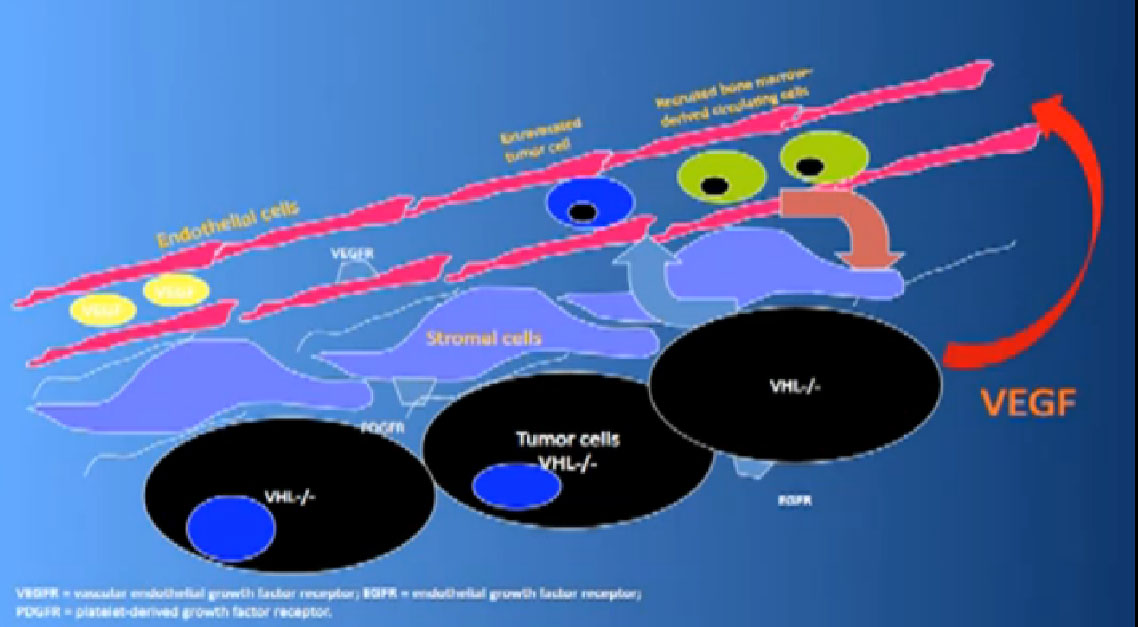

That infrastructure is as follows: When we think of cancer we can’t think of cancer cells. The cancer cells are in black on slide and in blue are the stromal cells–the “glue” cells, and above those the endothelial cells or blood vessel cells. This triumvirate plus other cells generate an organ—and it really is an organ—that we call cancer. And when we use therapies, we are blocking specific areas there.

I’ll tell you a bit about the therapies we use now and that some of you are on, and what they are actually blocking.

Here is some terminology you are about to hear, some jargon, as we talk about trials.

Progression free survival (PFS)—time it takes for cancer to start growing again

Overall Survival (OS)—time it takes from start of treatment to passing of patients

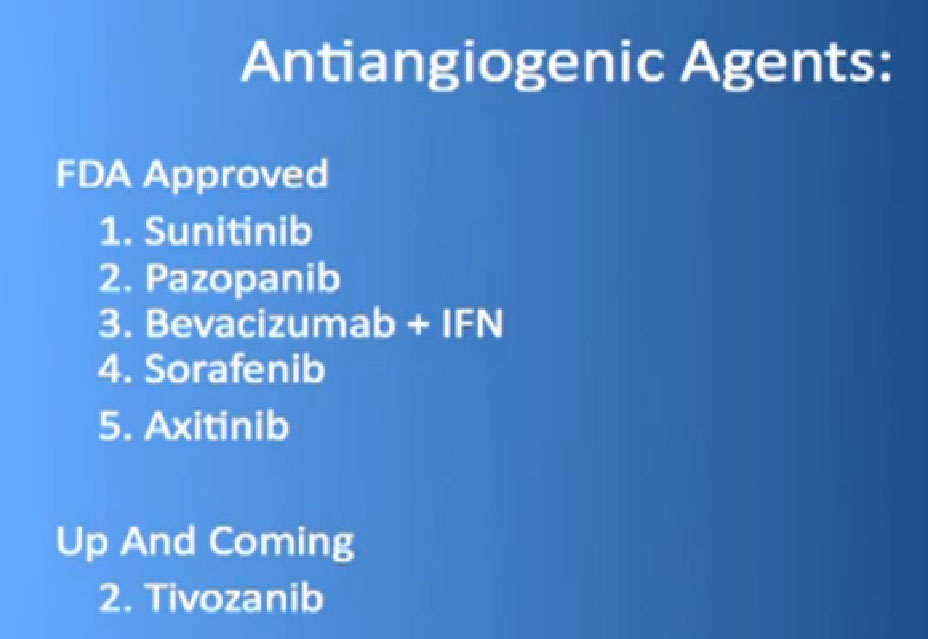

So the “blood vessel starving” are the antiangiogentic therapies we currently have are listed here, and I am going to go through each of these in details.

Antiagiogentic Agents FDA Approved

1. Sunitinib (Sutent)

2. Pazopanib (Votrient)

3. Bevacizumab- IFN (Avastin + Interferon)

4. Sorafenib (Nexavar)

5. Axitinib (Inlyta)

mTOR Inhibitors Mammalian Target of Rapamyin Inhibitors

6. Temsirolimus (Torisel)

7. Everolimus (Afinitor)

We also have some up and coming drugs. And the way these drugs work with graphic shown again—is they block the blood vessels. They try to kill the blood vessels that feed the cancer. They don’t seem to have much effect on the cancer itself. That is why you have encountered resistance. That we can shrink this down, this cancer, but we can’t make it go away. And what we need, and on our wish list, are kidney cancer cell-killing therapies for the future.

mTOR Inhibitors

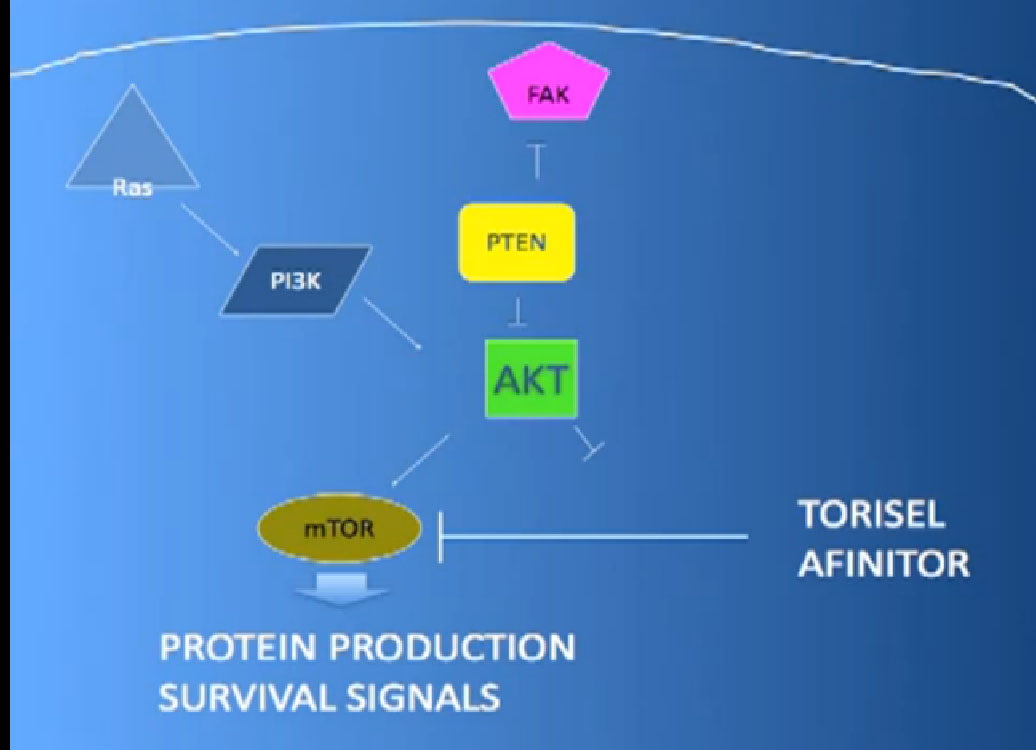

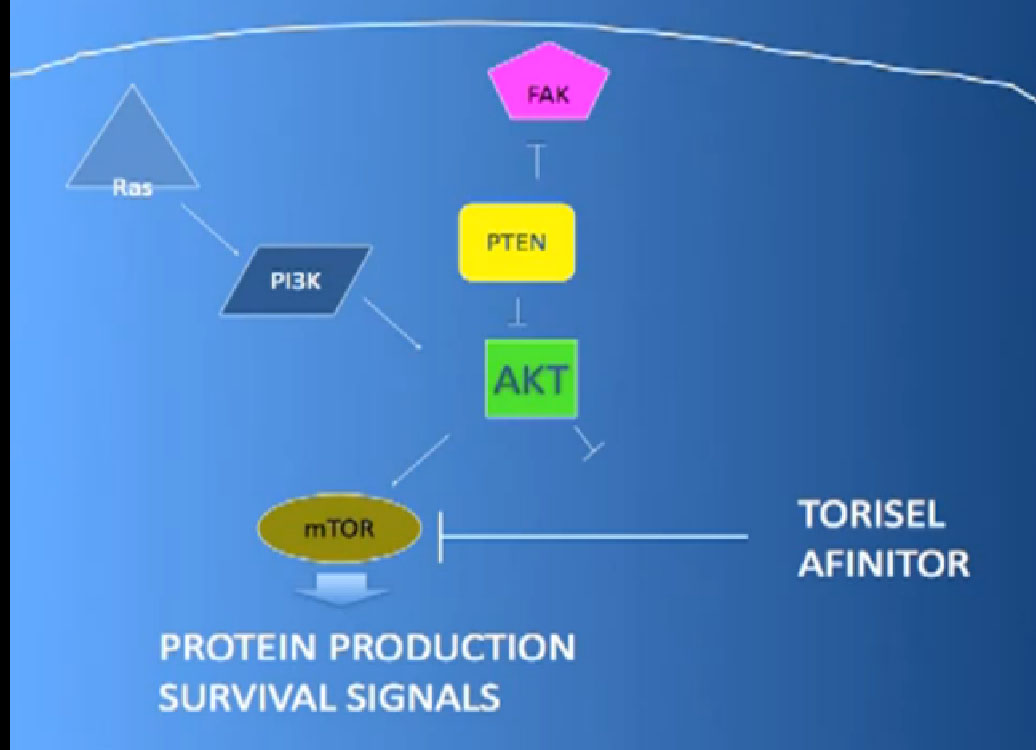

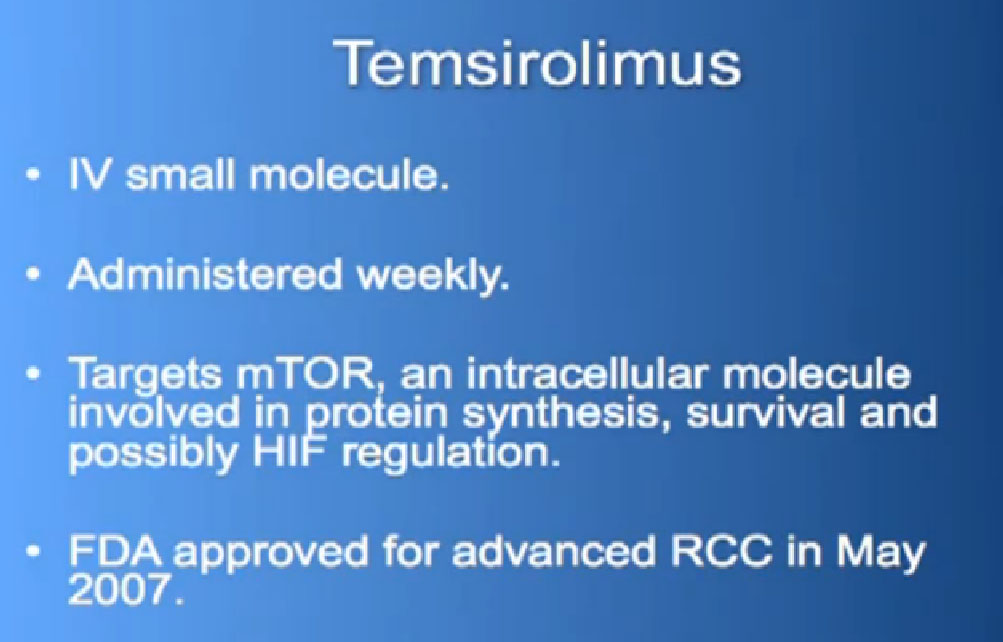

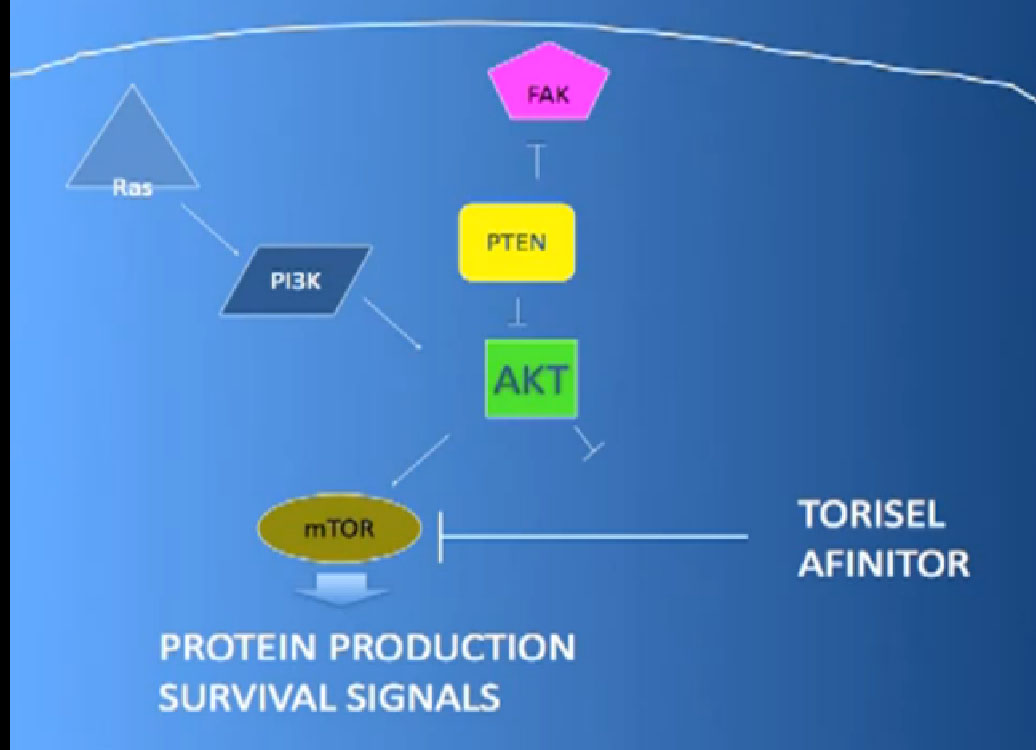

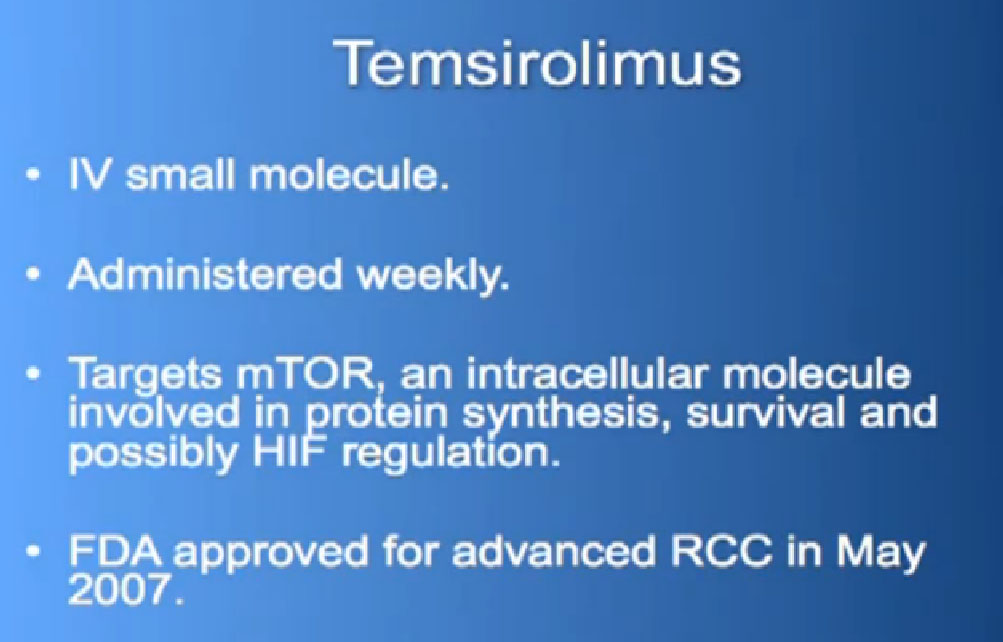

The mTOR inhibitors, of which there are two, Torisel and Afinitor ( Temsirolimus and Everolimus). What they do; they are actually working inside the cell perhaps both in the cancer cell and the blood vessel cell. And they are blocking particular proteins that seem to be up regulated, overexcited, that give them a selective growth advantage.

There we have on the bottom, kind of a brown color, mTOR, which if up regulated, results in production of and more survival advantage… for the cancer cells—which is shouldn’t have. What Torisel and Afinitor is block that signal.

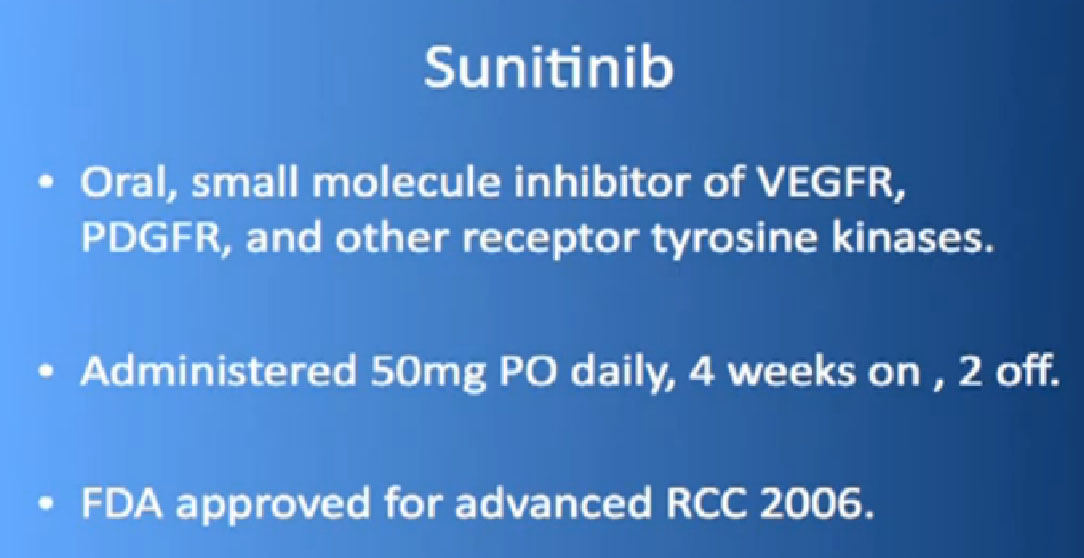

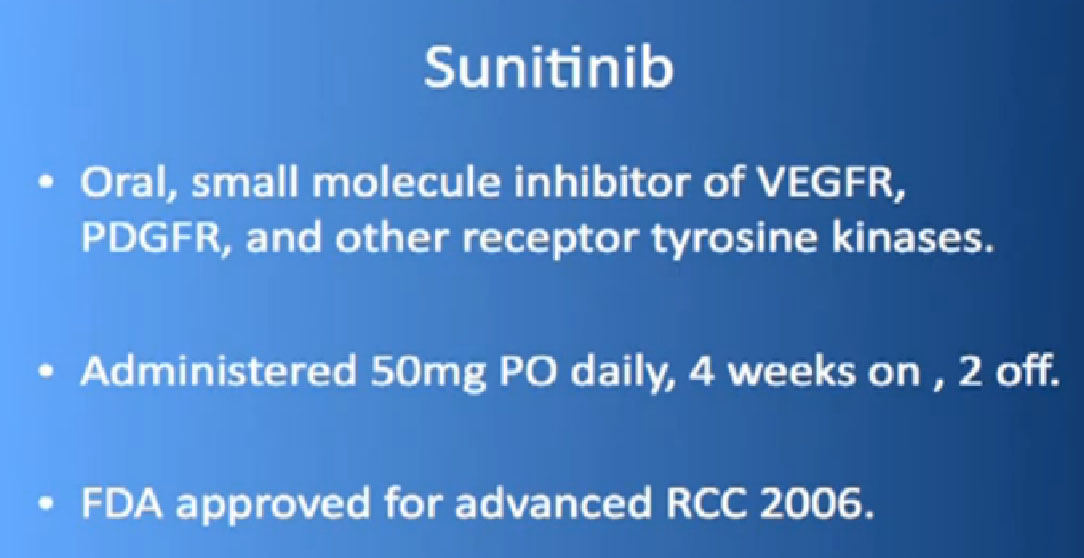

So let’s talk about the drugs that in 2012 were currently using. The one that is probably most commonly used is Sutent or Sunitinib. It this is a pill and what is does the block those blood vessel cells. It doesn’t seem to block the cancer cells that much. It’s given officially 4 weeks on, 2 weeks off, although I don’t remember the last time I prescribed that way for anyone. I tend to start 2 weeks on, 1 week off as I find people tolerate it better that way, and its FDA-approved now since January of 2006, amazingly, a long time ago. But it is pretty amazing that we have some people who are still on it, starting in January of 2006.

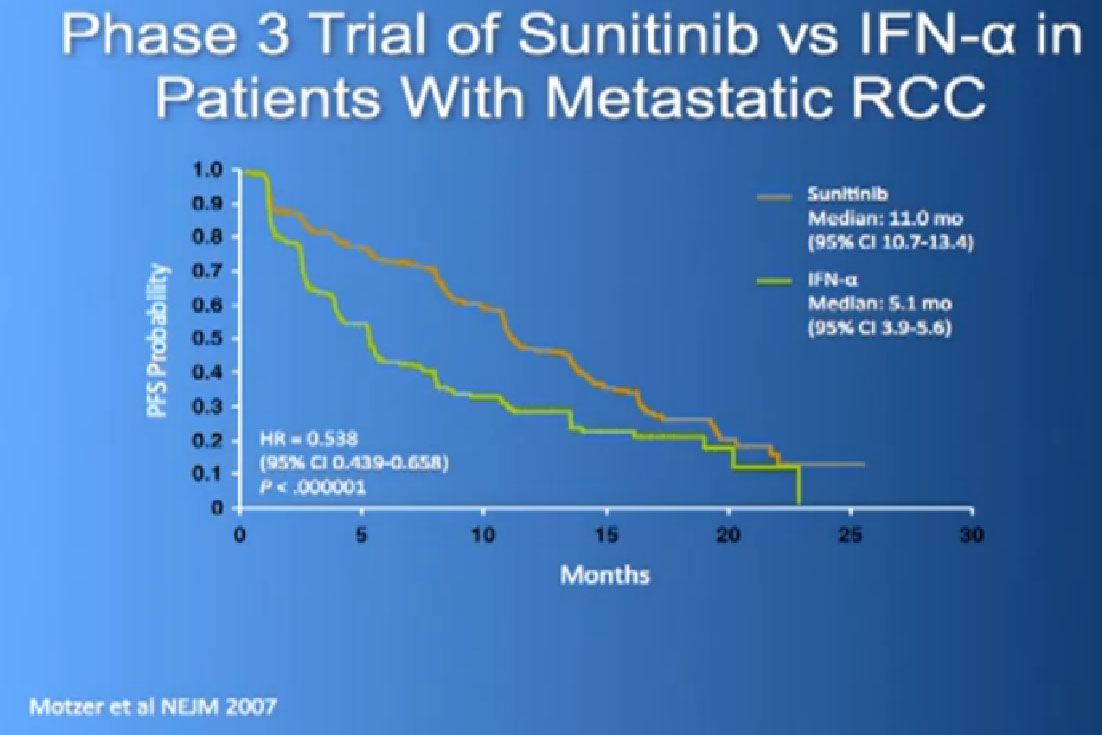

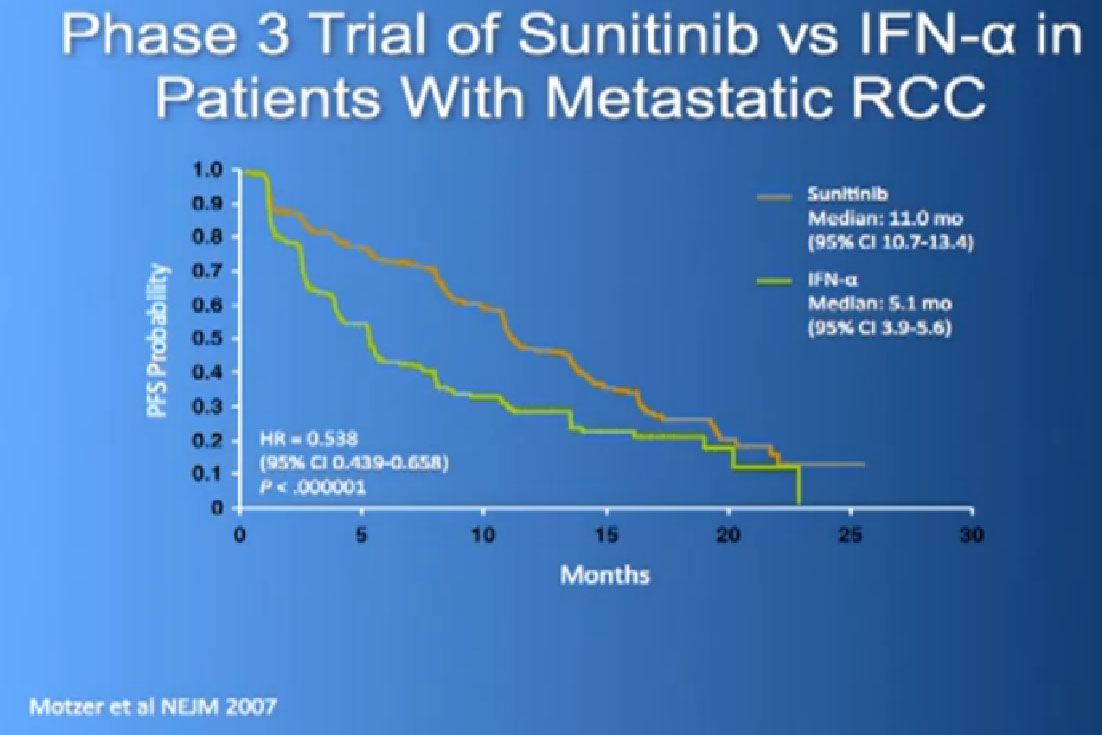

The reason this drug was approved, it was compared to the old standard of Interferon. What we found saw was a prolongation of Progression Free survival, the time it took for the cancer to progress. And this was doubled to 11 months from five months, with Interferon, which some of you might remember as shot you give under the skin, three times a week. And the top line is where the individual were progressing, where they were on Sutent, and the lower line is where people were progressing on Interferon.

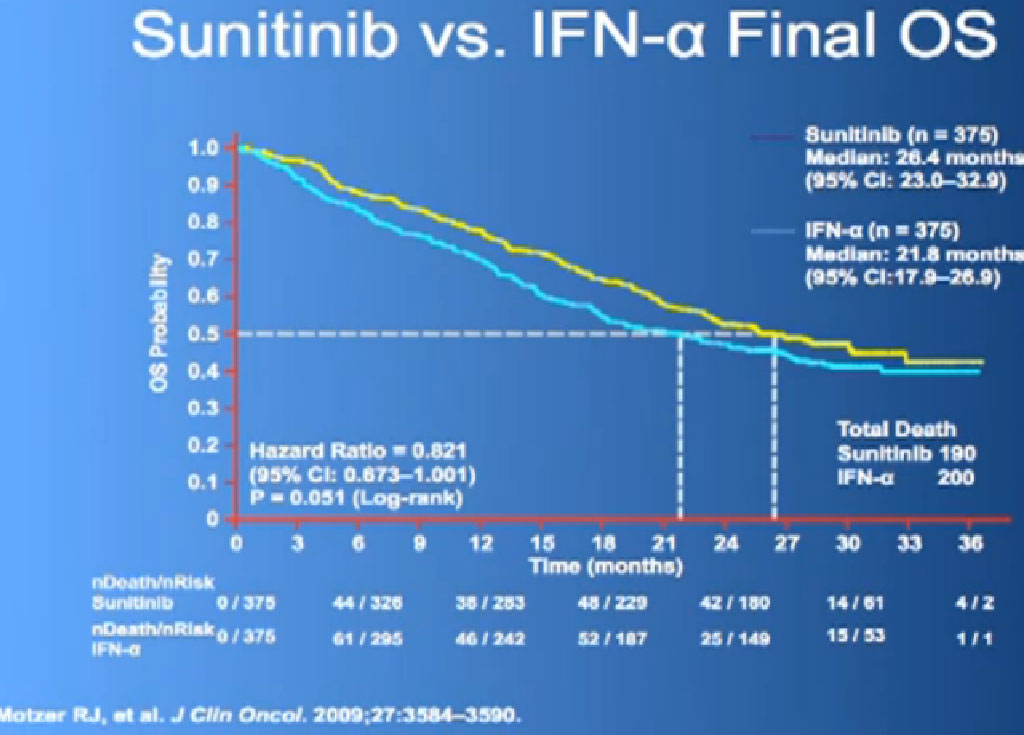

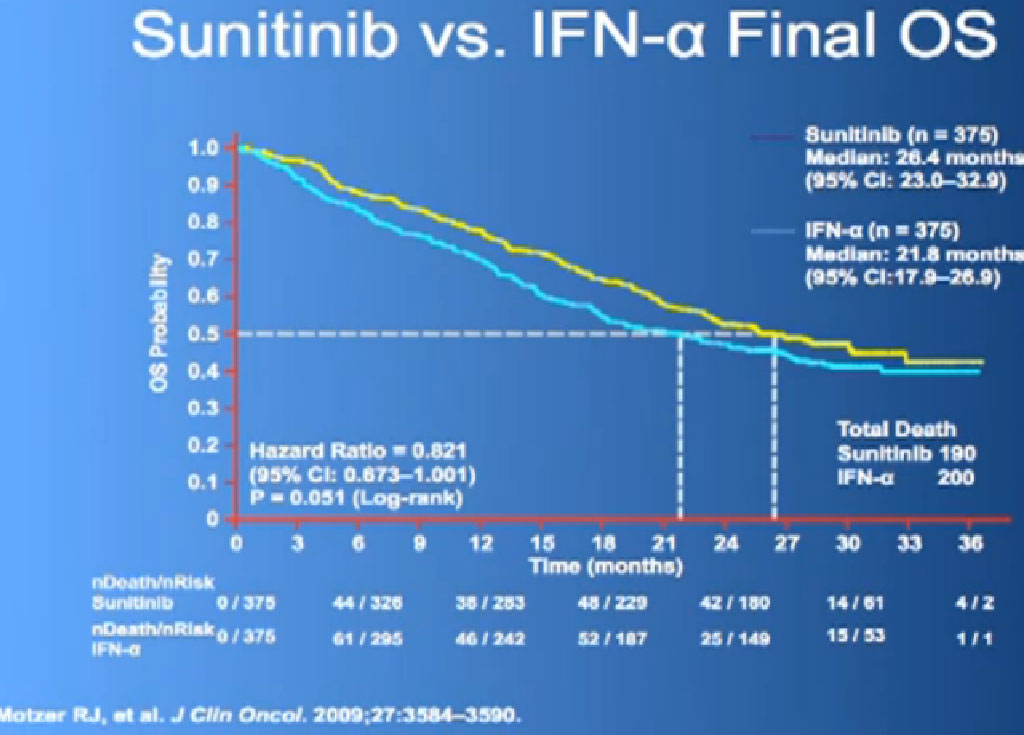

This is what is now call the Overall Survival curves, so essentially what we have here on the bottom is TIME, and the top lines the individuals that are still alive, and what we see on the top line are those on Sutent, and the lower line those on Interferon. It may not look like a huge gap, but what has happened on these research studies, when we do them, is what we call “cross-over”. When you progress on one of the drugs, you get to another and another and another. And the good news about this, it that it raises up the survival expectations to some degree, but it makes it hard to say, “That one drug is the one that is really making the difference.” Until we actually get therapies that consistently and reliably cure kidney cancer, we will still have this dilemma of having incremental benefits, but, “Hey, we’ll take them!”

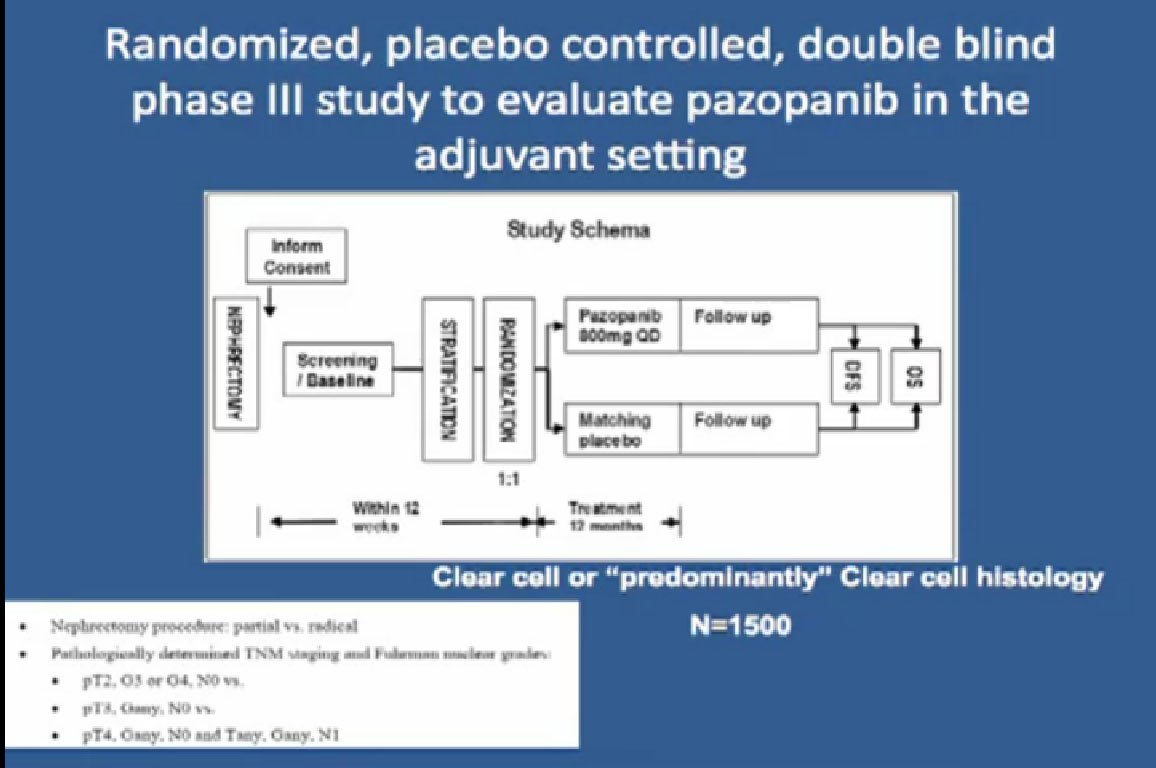

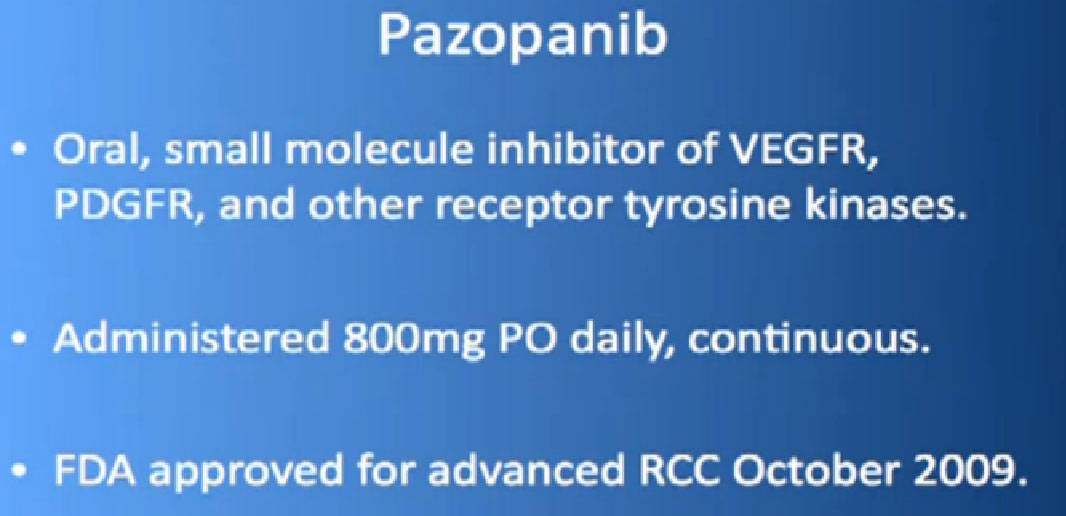

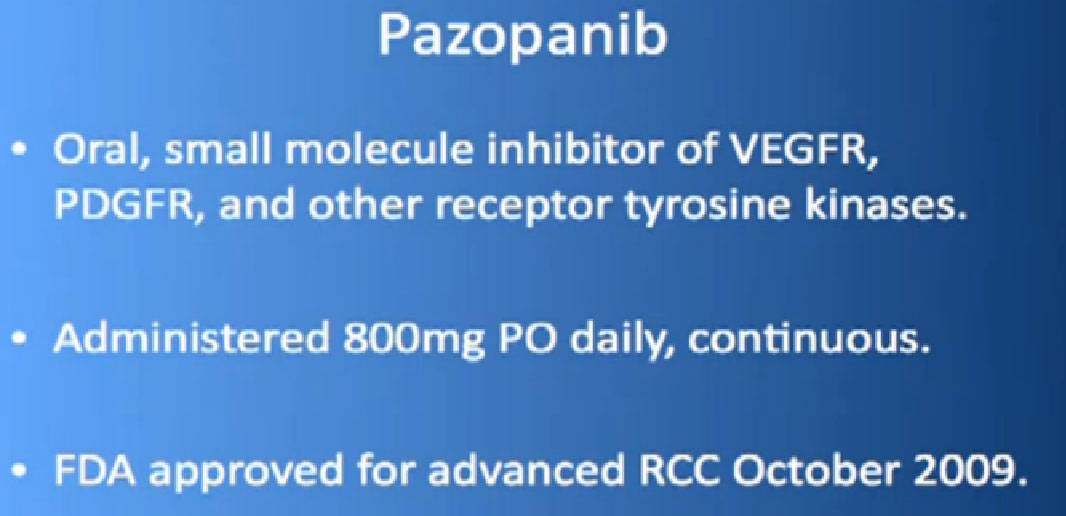

Another drug which has come out and has been used since 2009 is Pazopanib or Votrient. It’s an oral drug, given daily, once a day. Same sort of thing, a blood vessel blocking agent.

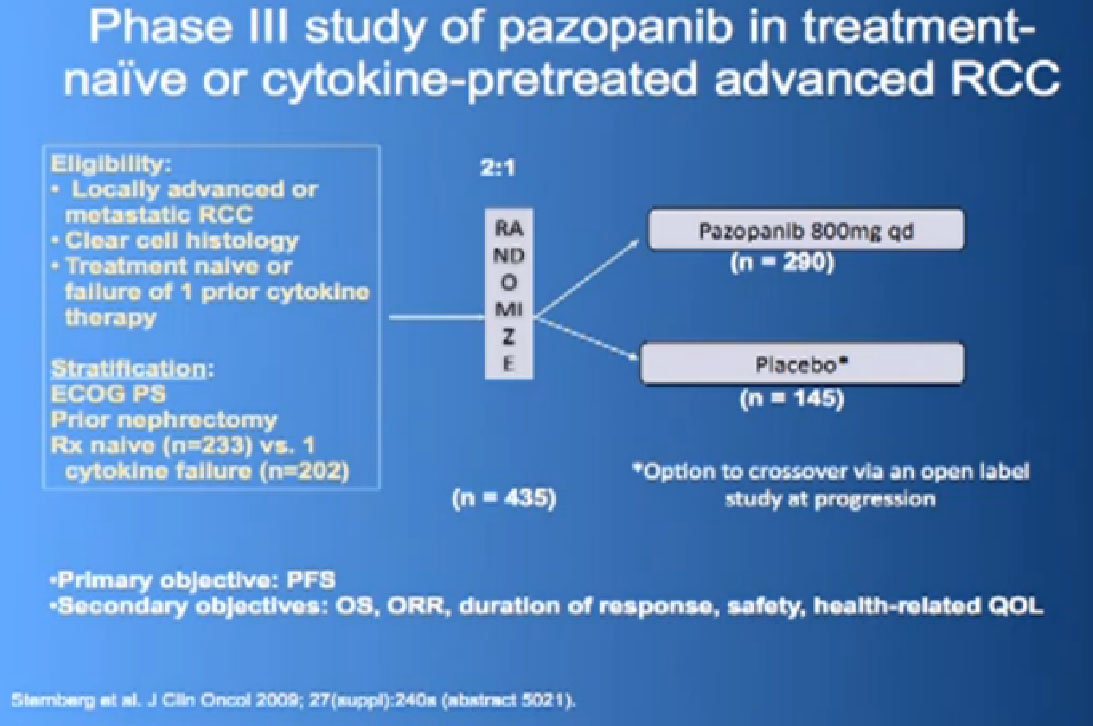

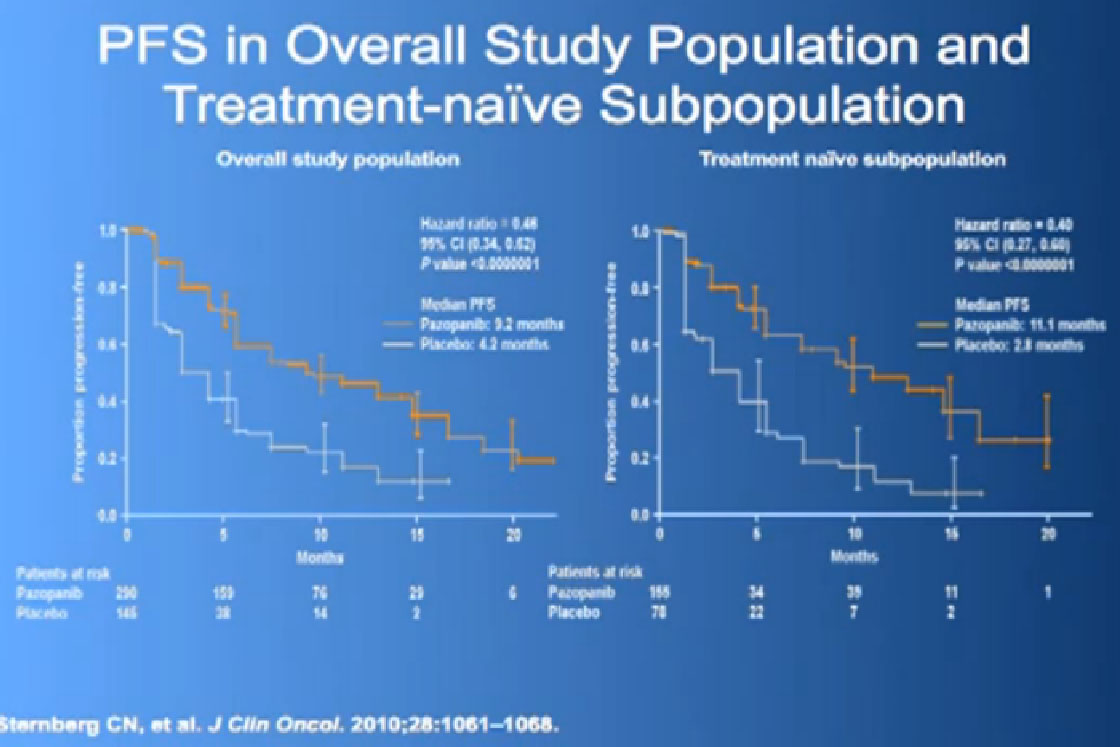

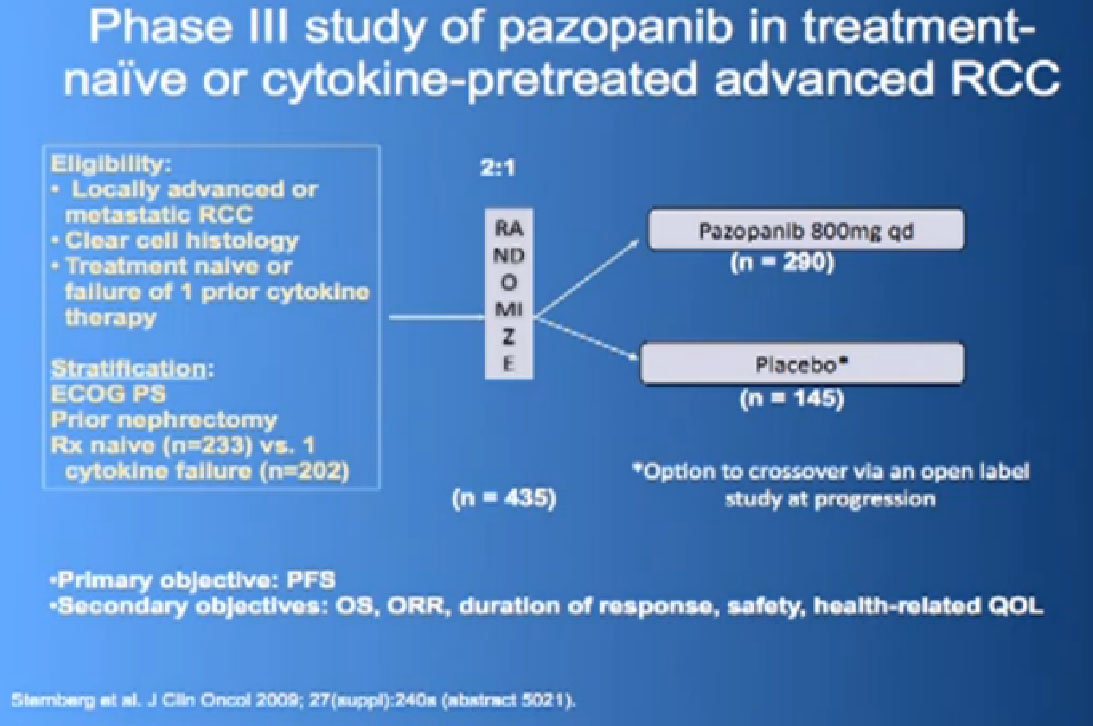

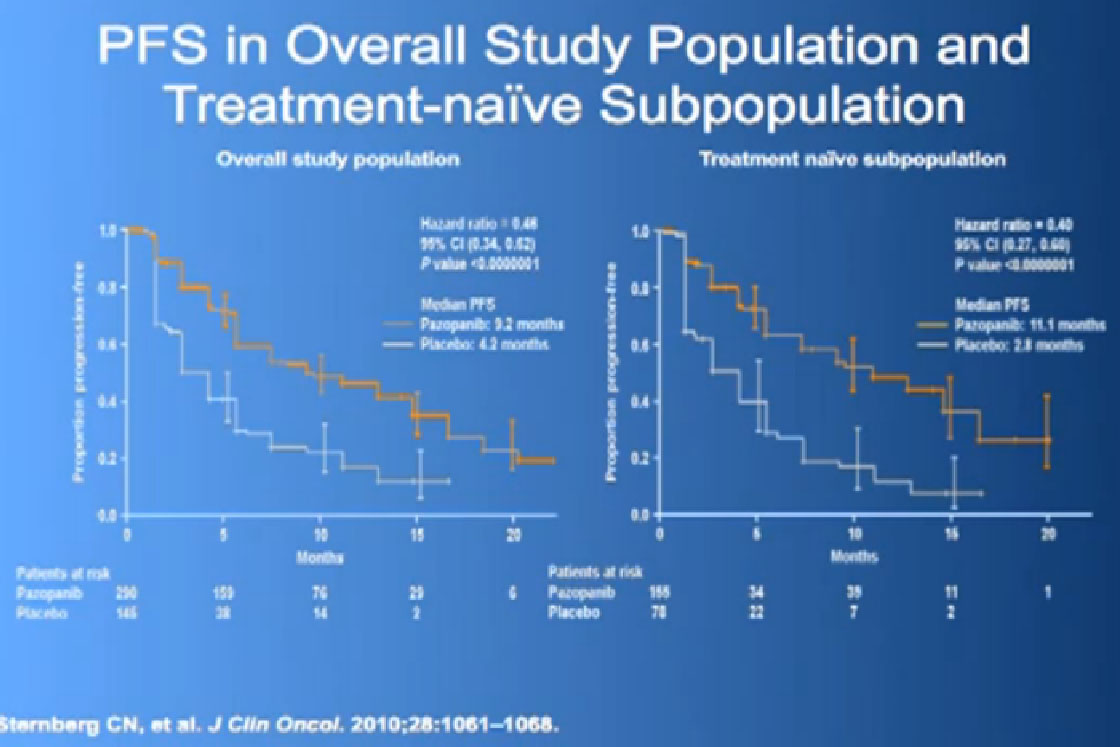

This was tested in a slightly interesting as you have study where you had no therapy before, or you had immune therapy, and they were randomized, randomly allocated between the Votrient (Pazopanib) or placebo. I have to say that most of the people were enrolled in non-US sites because it is a little bit of a hard-sell for people, if you have not had any therapy before to be told we’re going to put you on placebo, maybe.

Nevertheless, the trial was accrued to and it demonstrated a very significant progression free survival, the time to progression of the disease for the individuals on the Votrient compared to those on the placebo. And what we see on the left hand side here, we see one of these showing the charts, with the orange line on top is the group (with Votrient, )people who remained free of progression over time, and the lower line, the people on placebo. And the progression free survival data for the people who had not been on prior therapy was as good as we had seen with Sutent.

We had a trial that is currently completed and is being analyzed to see if Sutent is better than Votrient, and we still don’t know which is “better”, but Votrient is certainly gaining traction because of the fact that it looks kind of promising.

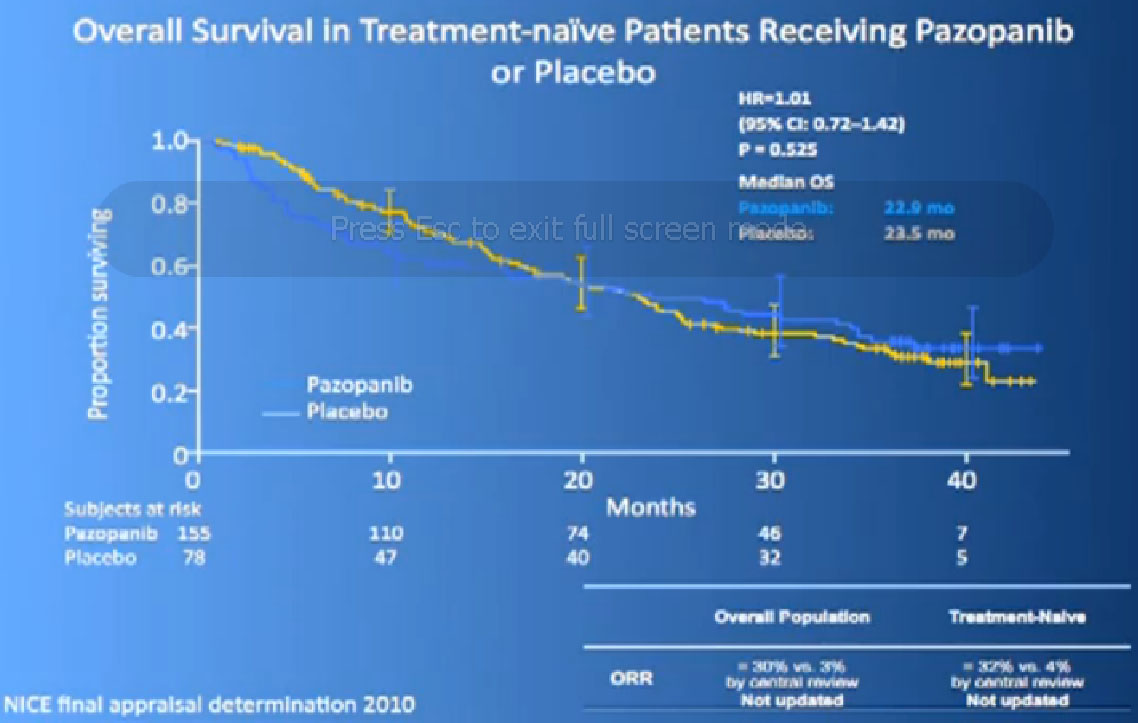

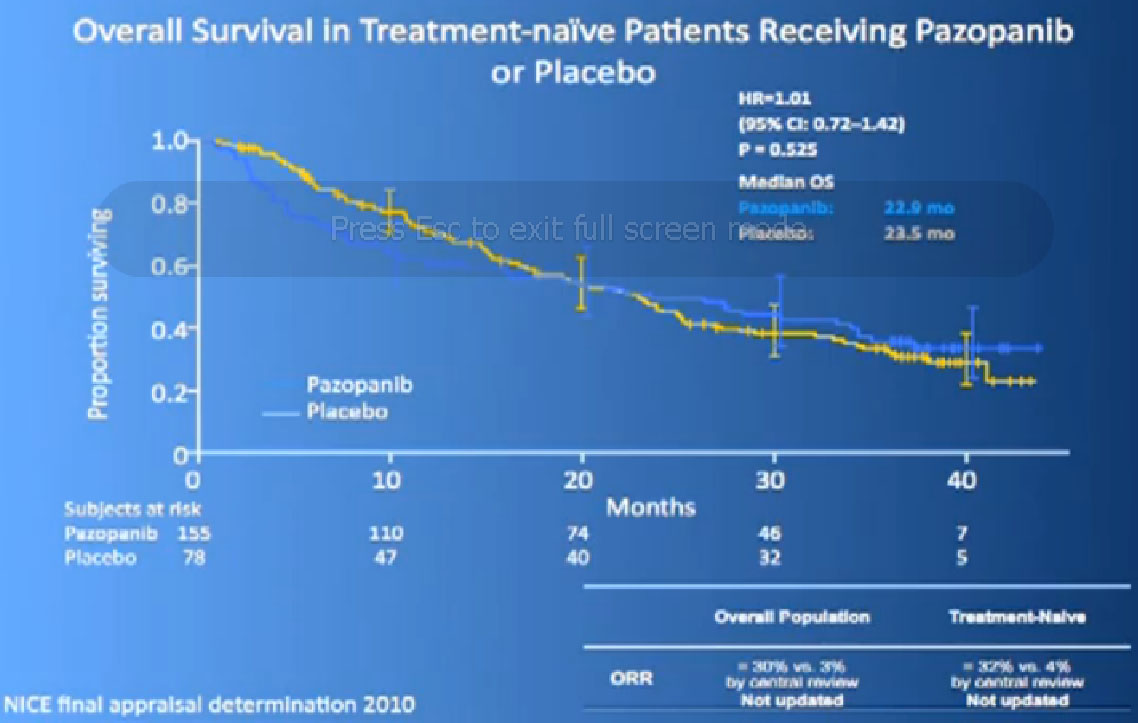

Now its interesting when they did Overall Survival analysis, they did not succeed in showing a big difference, because as lot of people had gotten onto Votrient when they were on placebo at the beginning, and they got onto all sorts of other drugs.

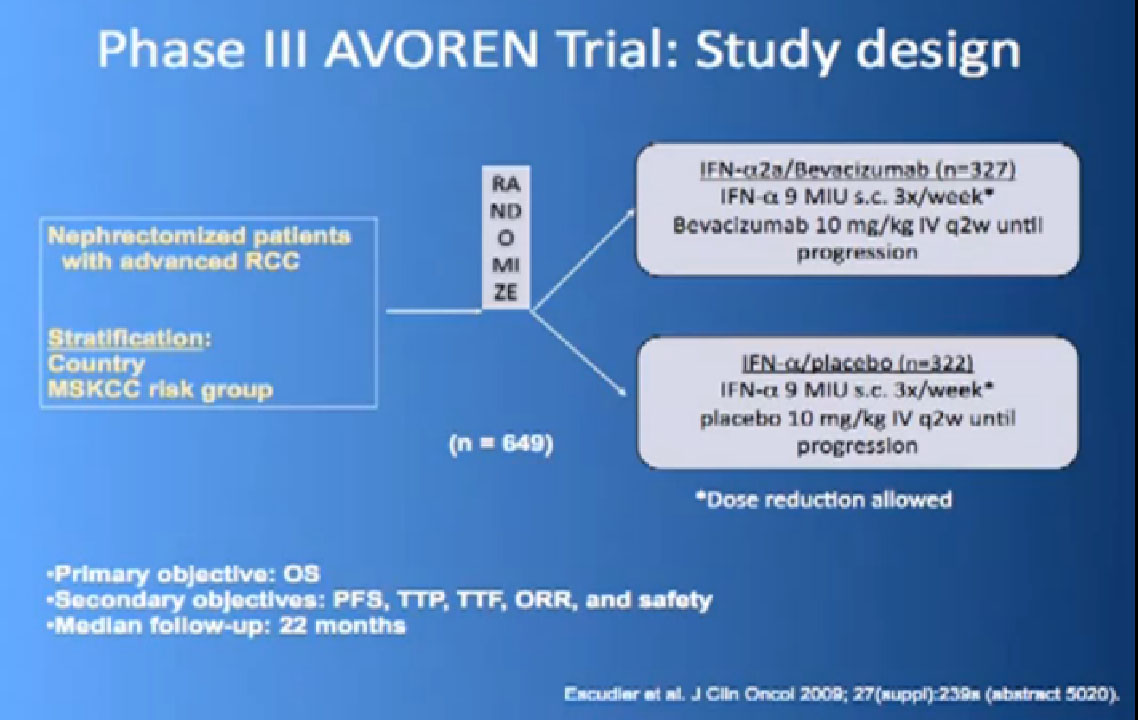

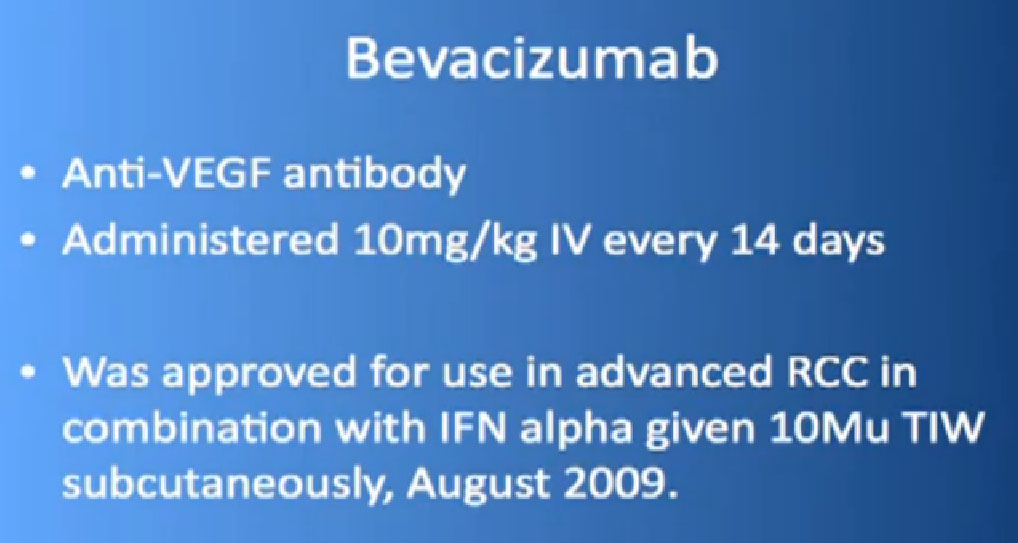

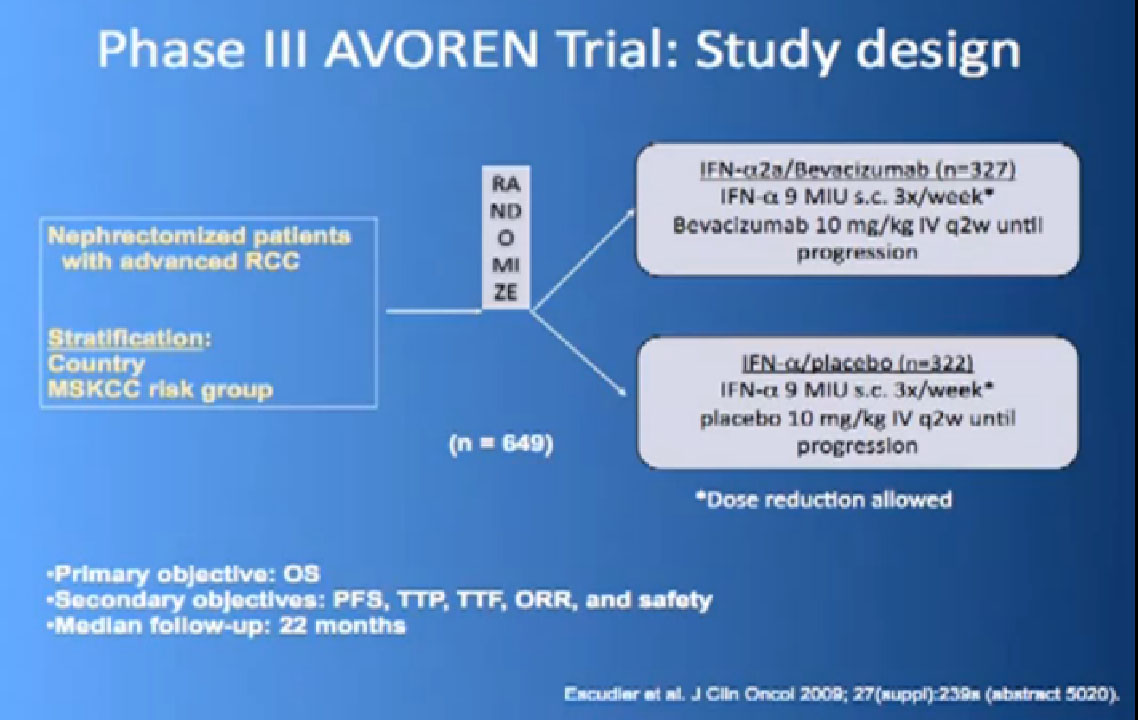

So the next drug we are going to talk about is a little different (Avastin). What Avastin is –it’s an injectible antibody against the thing the cancer produces, the VEGF circulating in the circulation. It tries to take it out of circulation, so the blood vessel cells can’t see it. It’s given every two weeks, by injection, and officially given with interferon three times a week, so a little less attractive for some people.

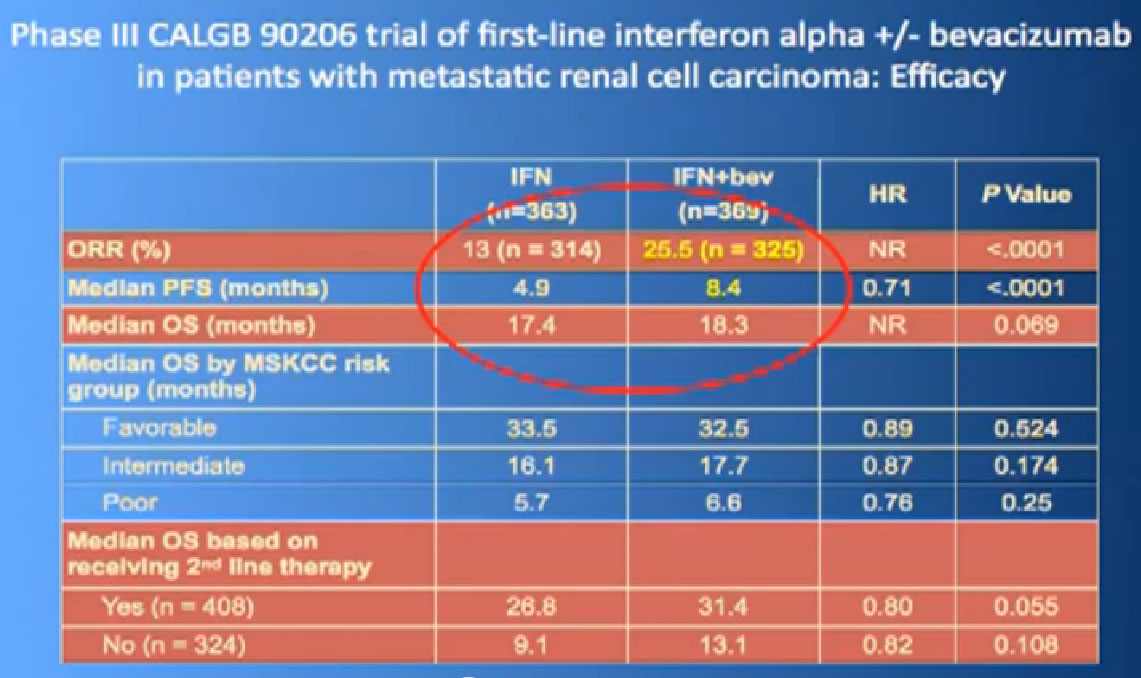

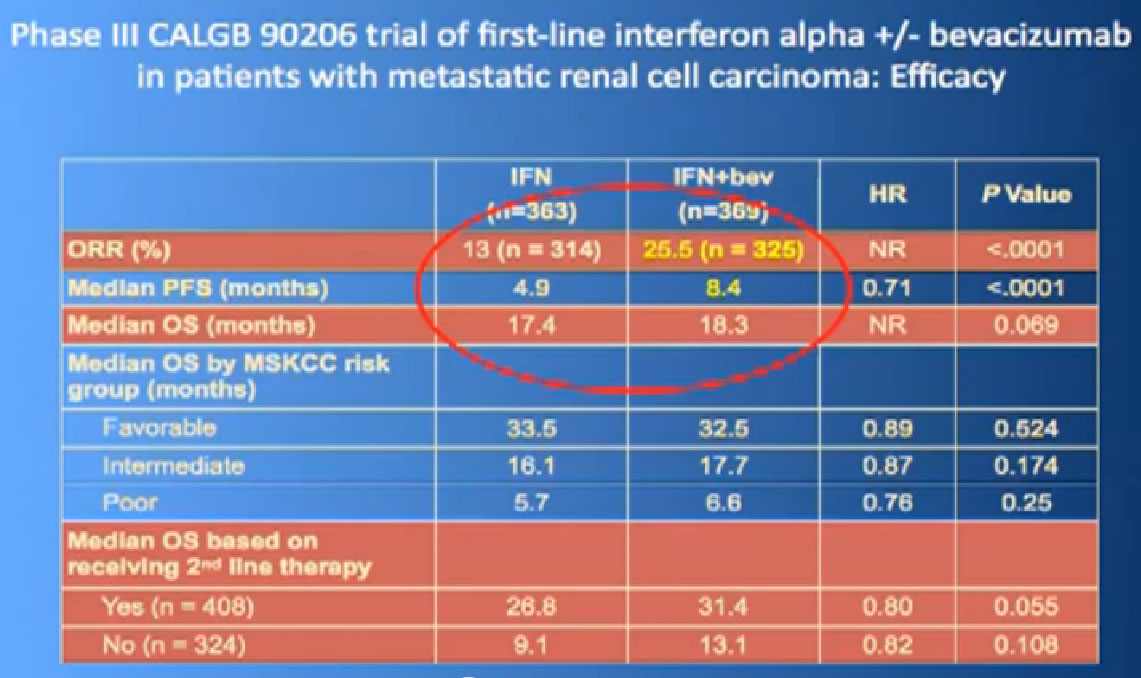

This is a bit messy to read; the progression free survival in combination with interferon is substantially better than interferon alone, and this was done to two different studies and the data were true in both these big studies.

Thus we’re pretty confident, that along with Sutent, and Votrient, this prolongs progression free survival.

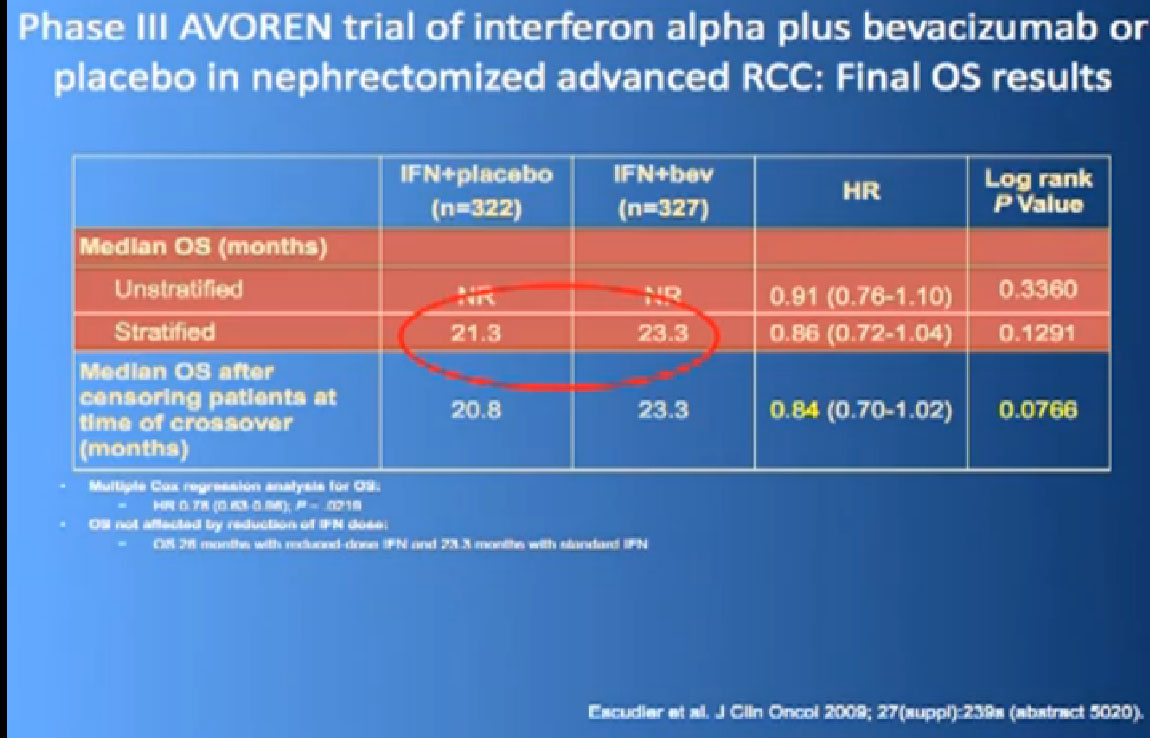

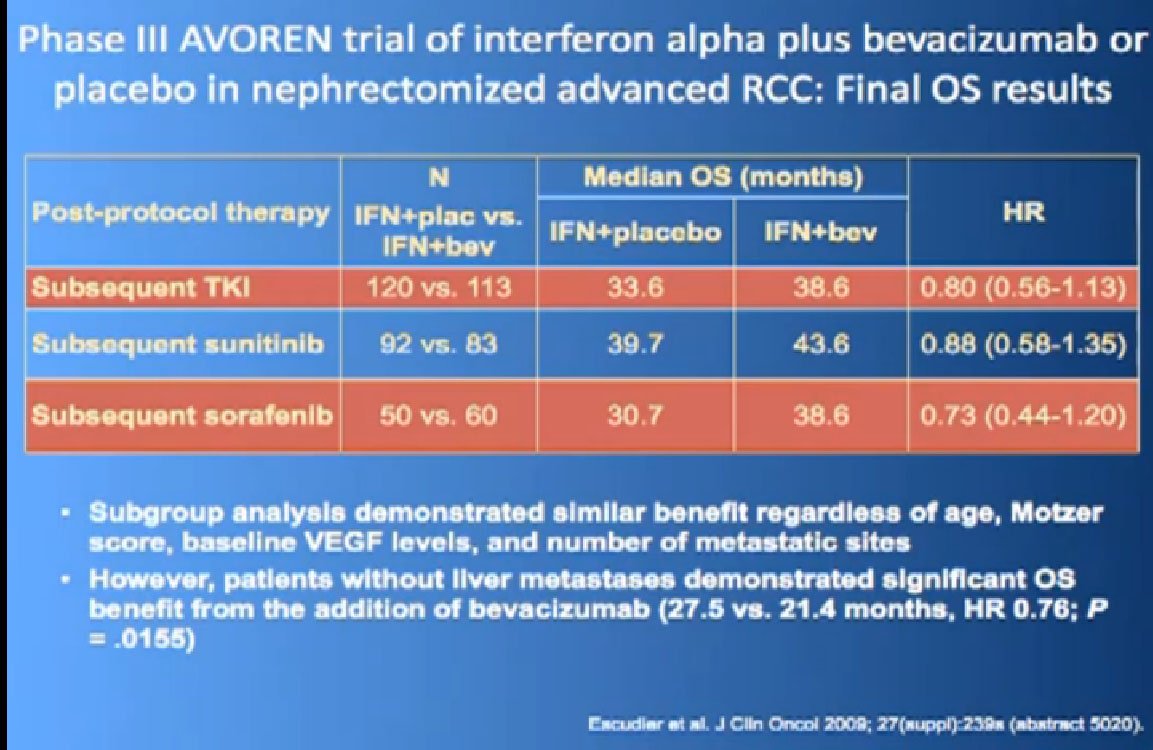

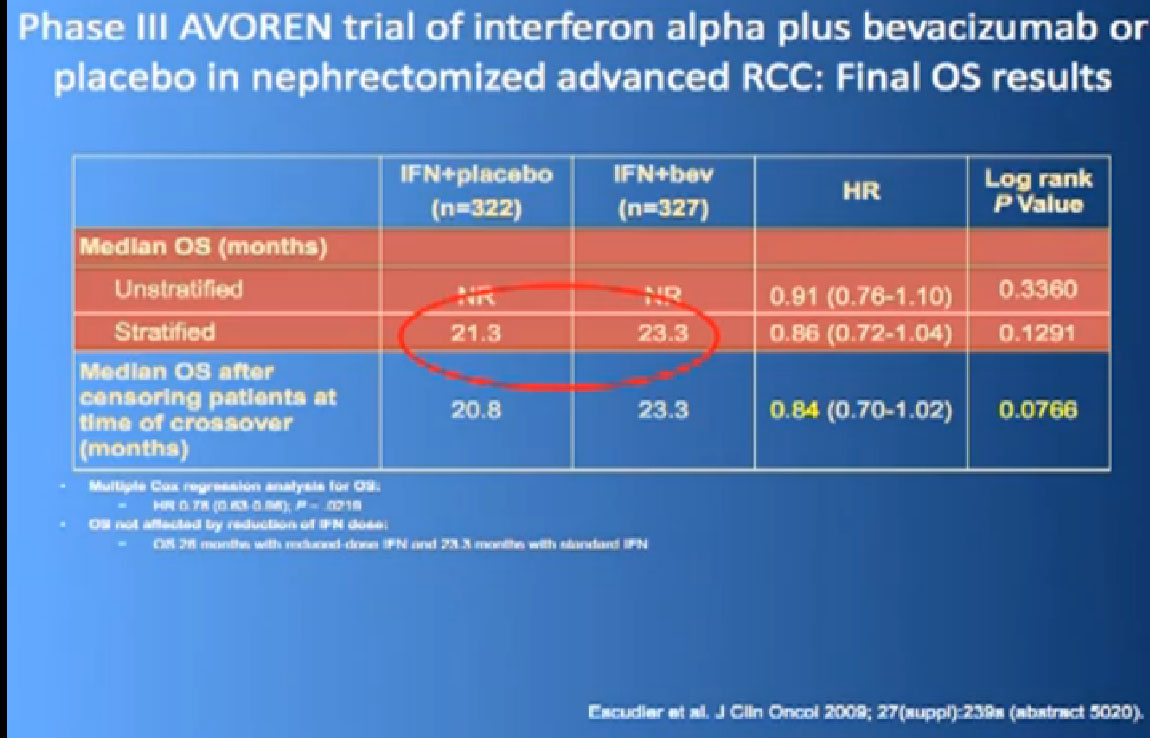

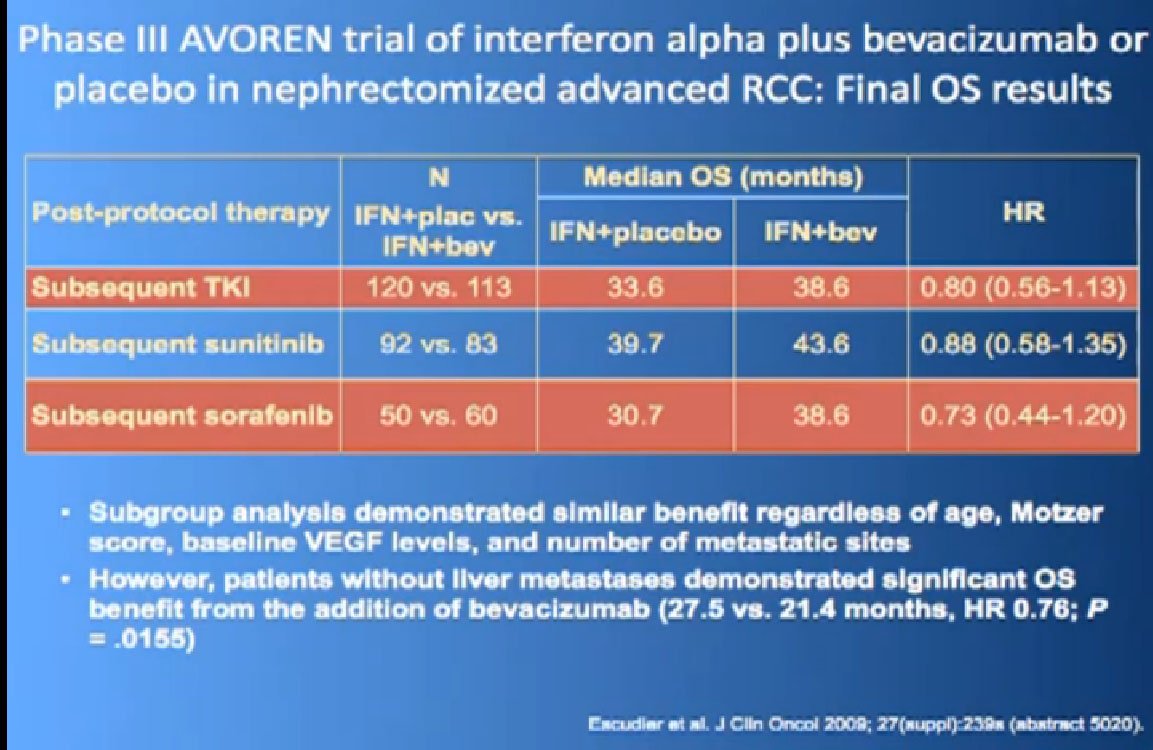

In terms of overall survival, 21 month for the interferon group, and next to it the interferon and Bevacizumab, 23 months. Again, in the same ball park as we were seeing with Votrient and Sutent, and not a statistically different figure. That statisticians take these numbers and crunch them and take p values and such, but still there was a lot of cross over data, and clearly, we are moving up the bar here.

One of my favorite data pieces is from the Sutent study. The patients on that Sutent study who had received Sutent or interferon were treated in countries where there was no opportunity for second line therapies or 3rd. All they got was Sutent or interferon. And the people who were on the sutent arm only, and nothing else, had a 28 month survival, and the people who received interferon only, had a 14 month survival. So that’s an untarnished bit of data, showing the magnitude of benefit that they were receiving. That is more reflective of what we are seeing in our clinics today.

I wont’ go into this in detail, but bottom line is that. There’s a lot of number and you are probably getting numbered out. Bottom line we look at historical data compared to these people who are on these drugs and then get subsequent drugs, and we are seeing survival in the two to three to four years. Also known as Nexavar

Also known as Nexavar

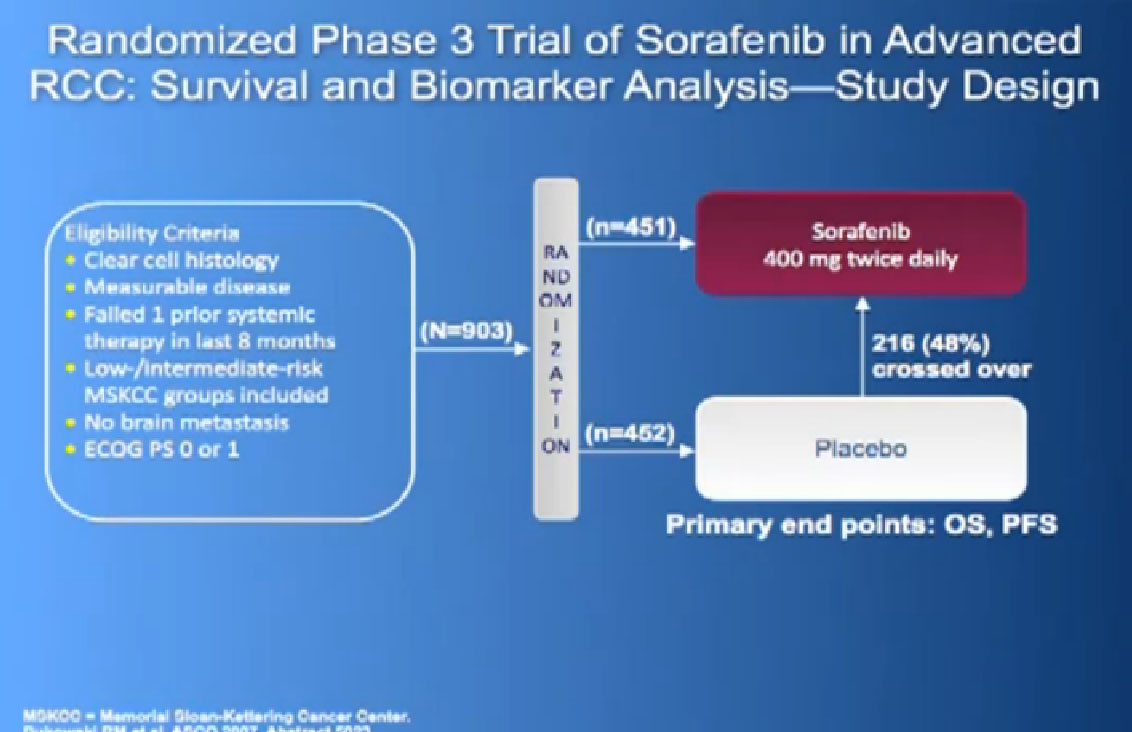

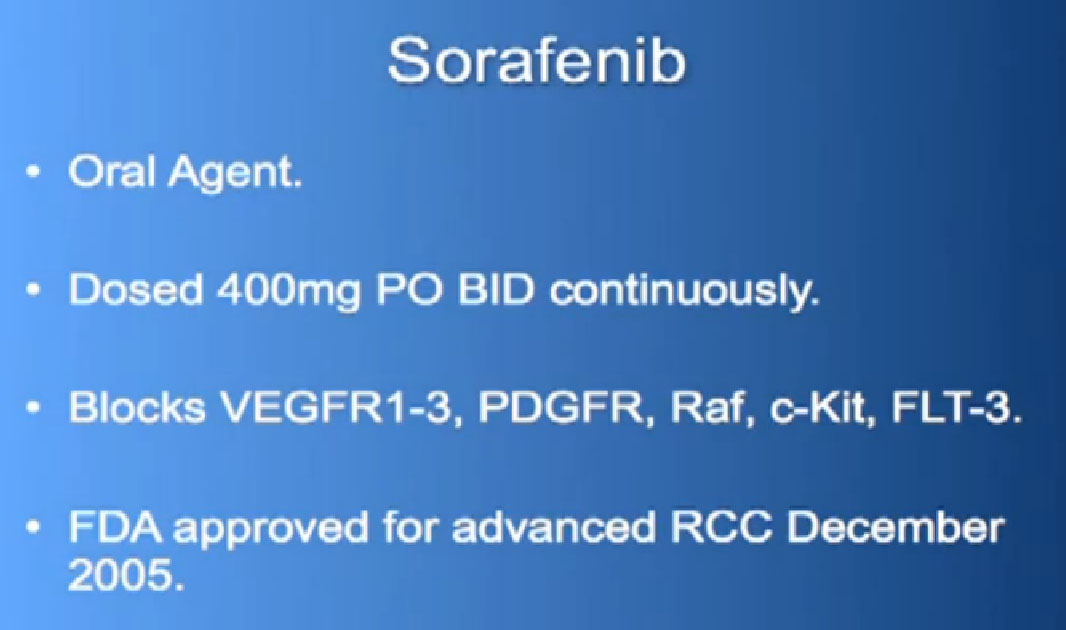

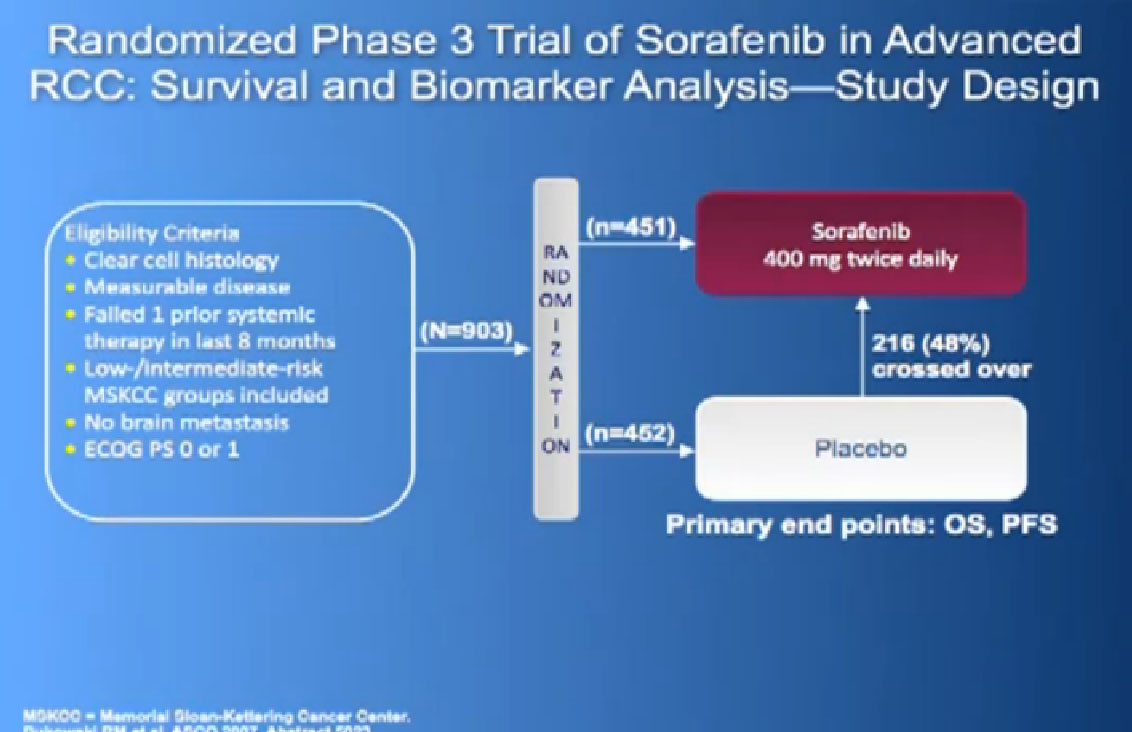

The next drug we are going to discuss is Nexavar, which was approved in 2005, the first of these drugs to be approved. Same deal, the blood vessel starving drug, given twice a day, orally.

It was given initially to people who had not been given any targeted therapies before, but had progressed on immunotherapy and it demonstrated that there was an improvement in progression free survival again.

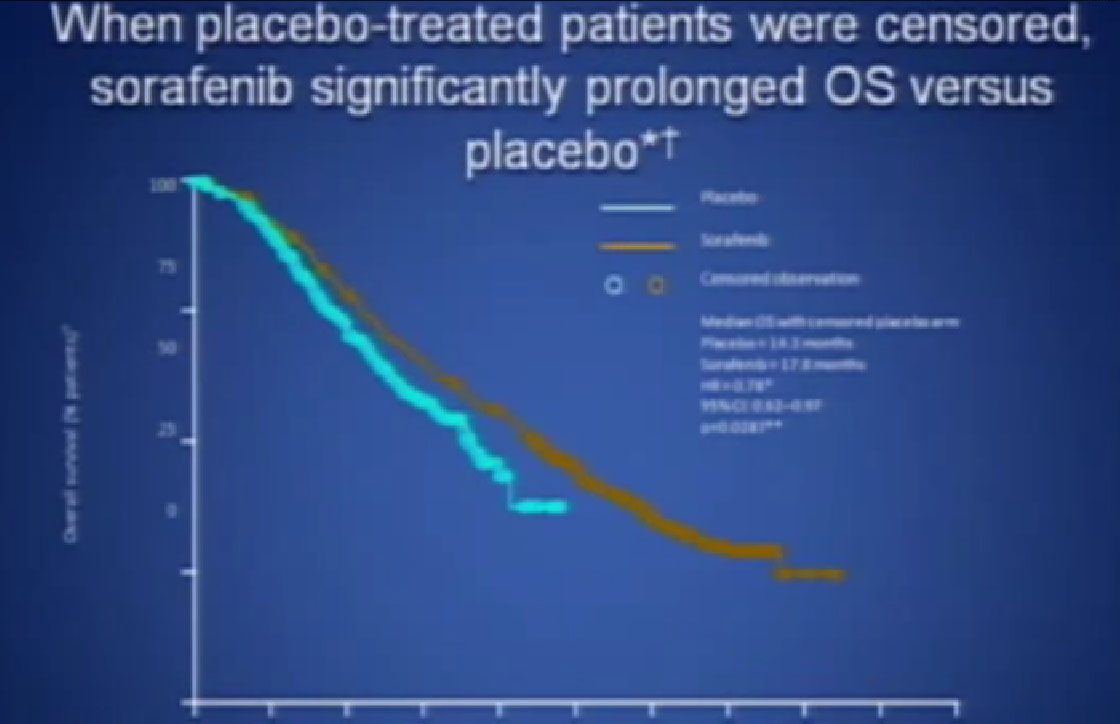

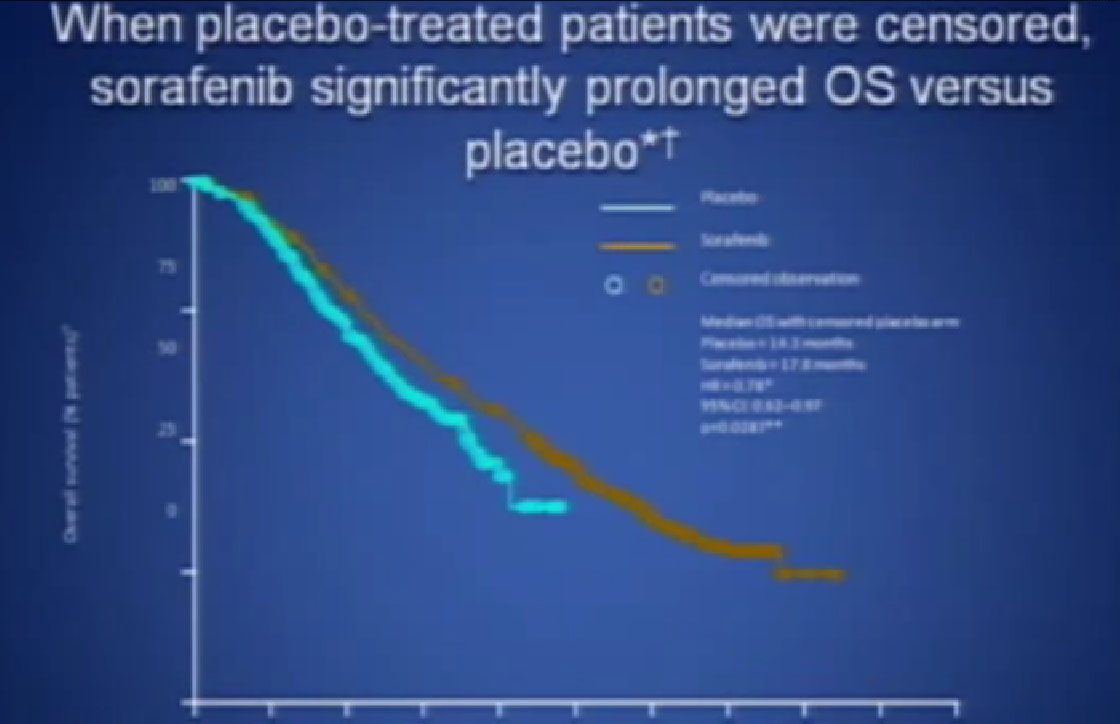

If you looked at Overall Survival there was improvement if you took out those people who crossed over. So again, modest improvements and definitely doing something for patients.

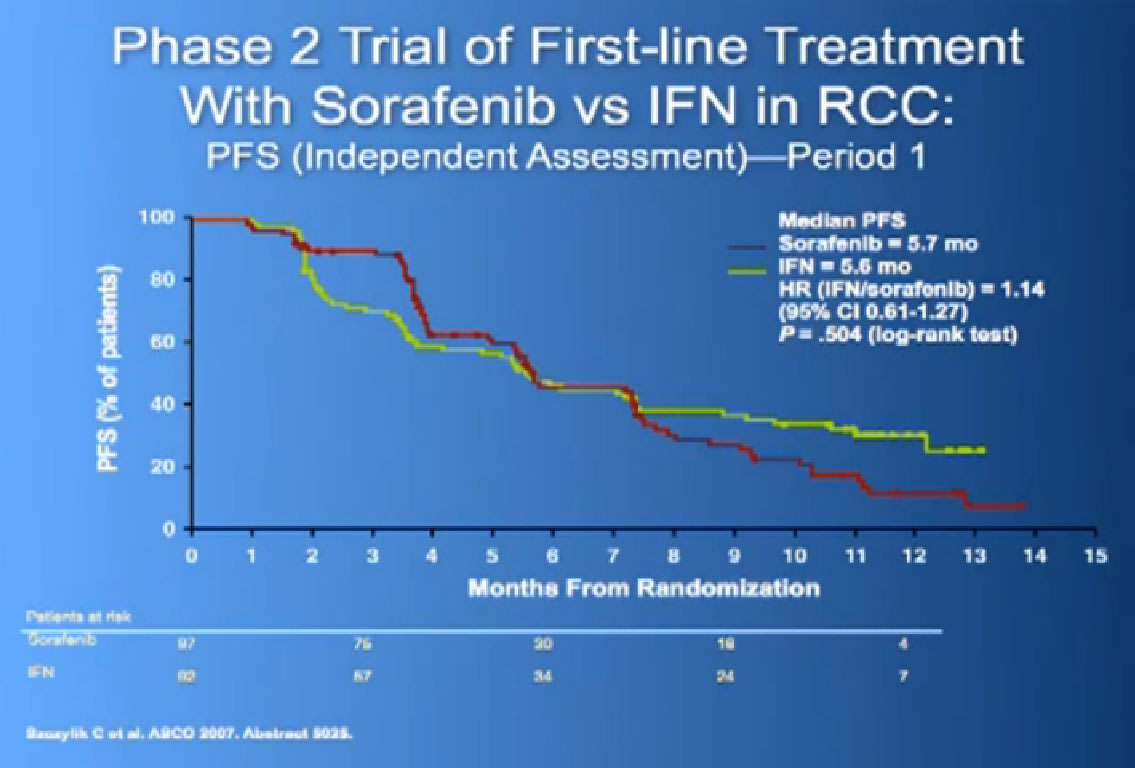

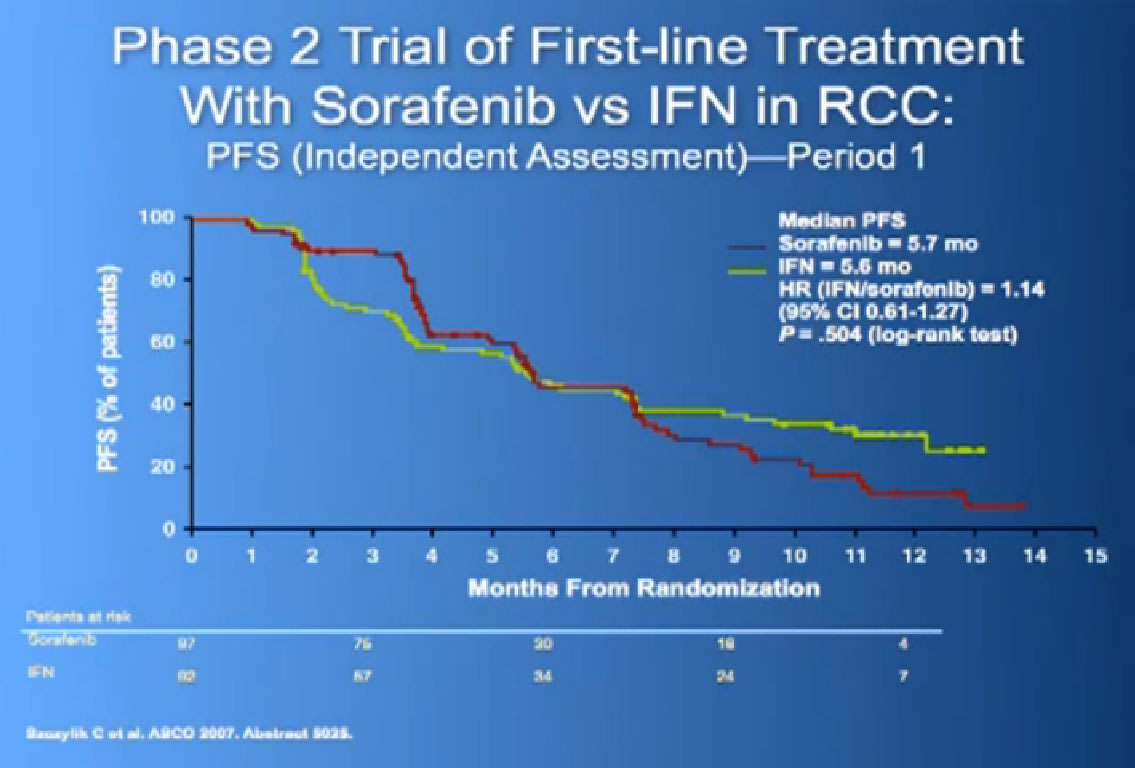

Now when this drug was compared directly to the untreated patient group to interferon, what was happening, was that it did not look like it was better than interferon alone. I just finished telling you that Sutent, Avastin, Votrient all beat interferon, and here we have a drug, that seemingly, didn’t. Subsequent studies were done which shows that PFS is somewhat better than this trial, but in reality in 2012, this drug is not much used in front-line therapy, for better or worse. It’s not that commonly used, and personally don’t use it much, based on these data.

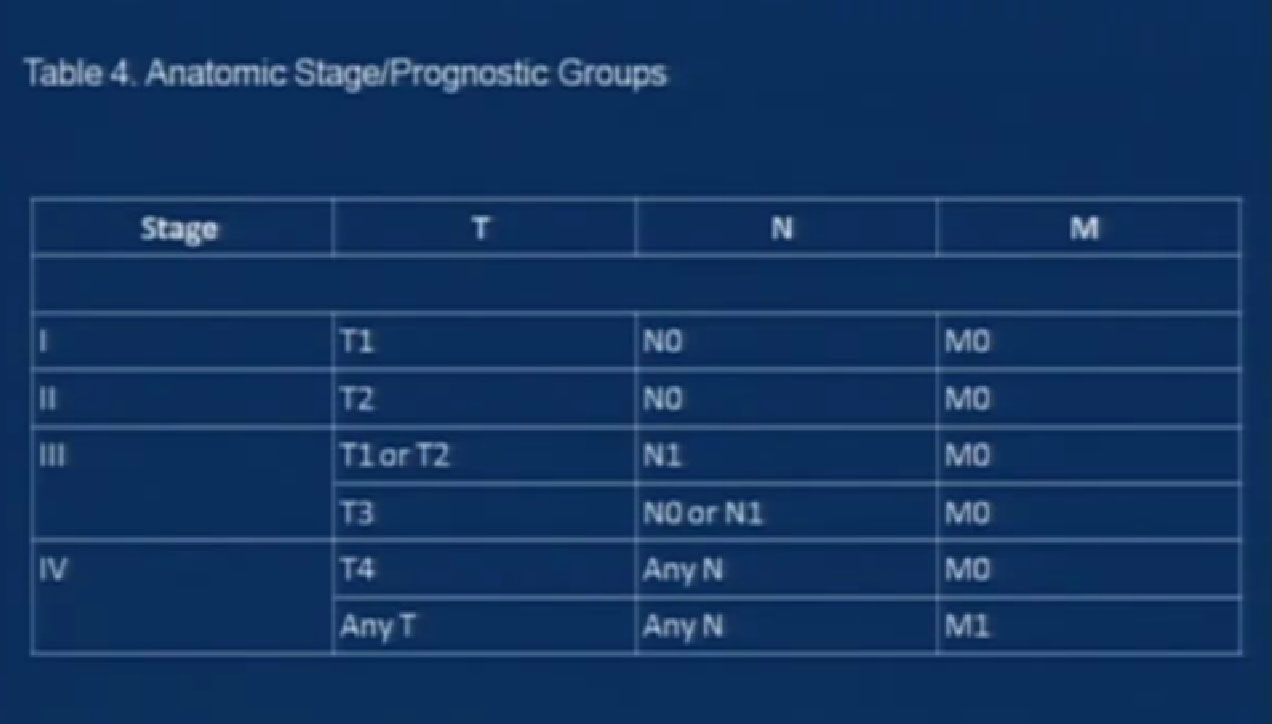

What I have been talking about now, has been about individuals who have clear cell RCC, good risk features, and these are features looking at “are you anemic?, is your calcium elevated?, are you feeling and so on.” These are risk features to decide if a patient is in a good or intermediate risk category versus a not so good category.

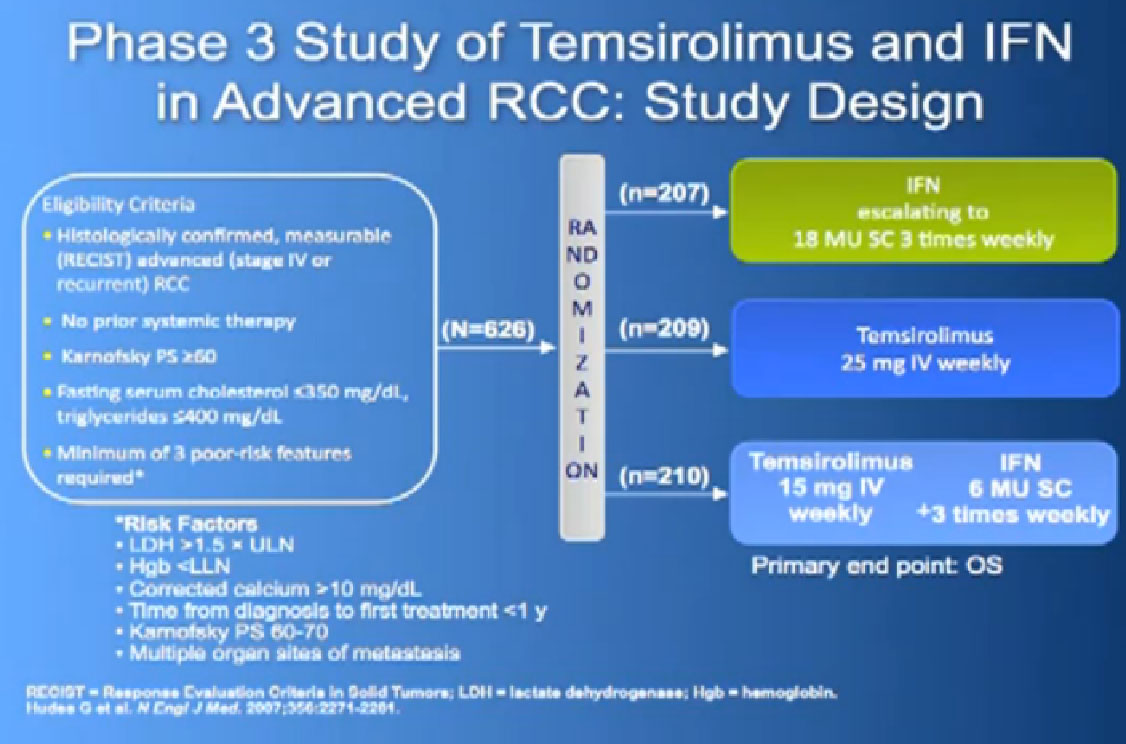

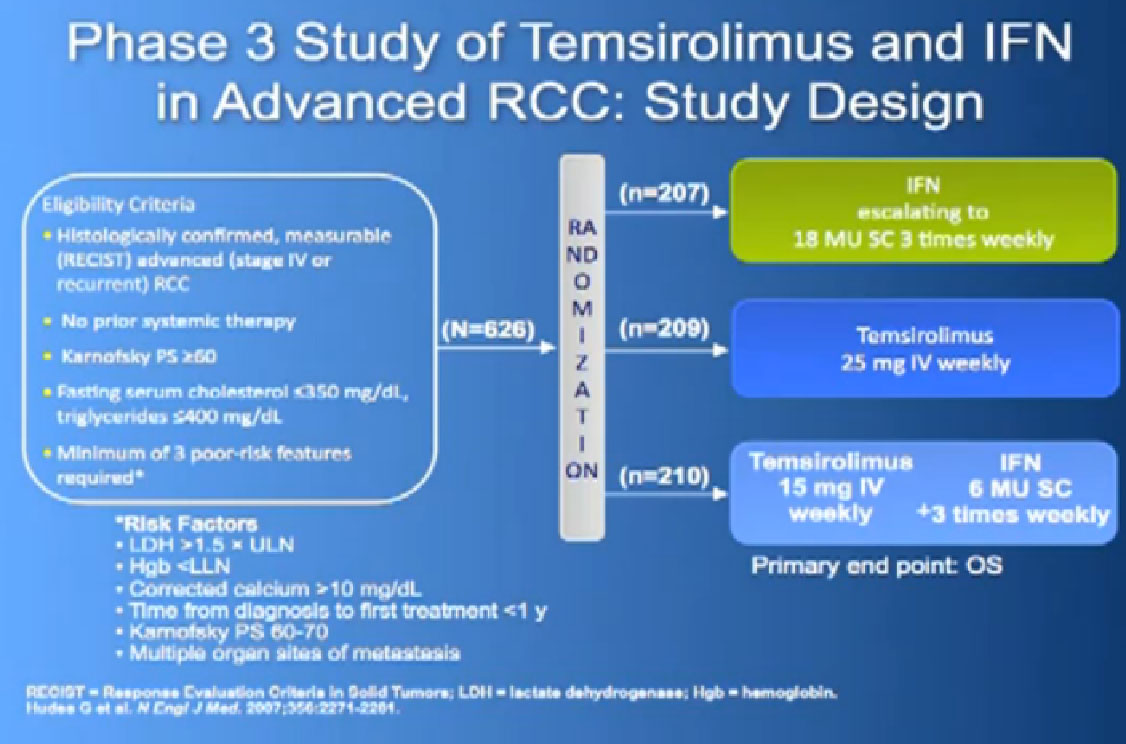

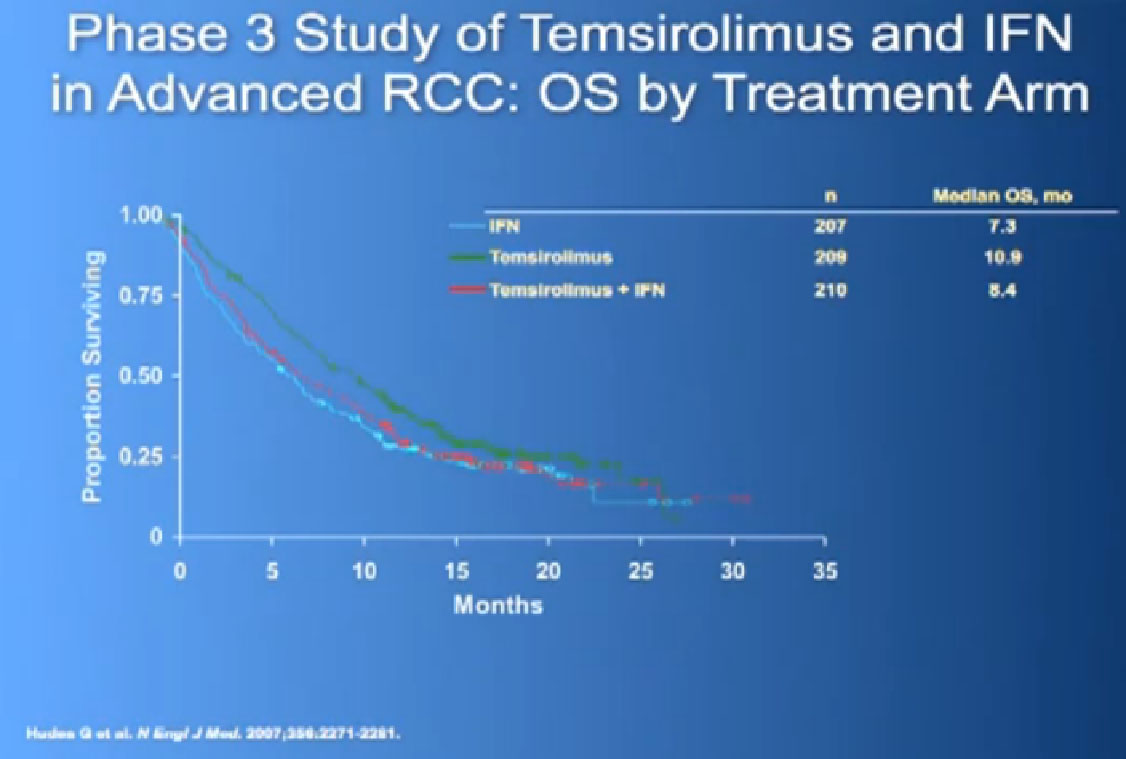

And Torisel, an mTor inhibitor, which I talked about before, and was tested in this poorer risk population of patients, and was approved in 2007. Essentially, they took patients who had not had any prior therapies, and they checked off boxes. Do you have a low performance status?, your “good feelingness”, have you had your kidney removed before or not?, have you had anemia?, have you had high calcium?, have you had high LDH?, six categories in all. If you had at least three of those negative categories, they said, “OK, we’re going to put you on Torisel, and compare you with interferon and with Torisel and interferon in combinations.” And because they know this group of individuals tends to have a lower overall survival, they did an overall survival study.

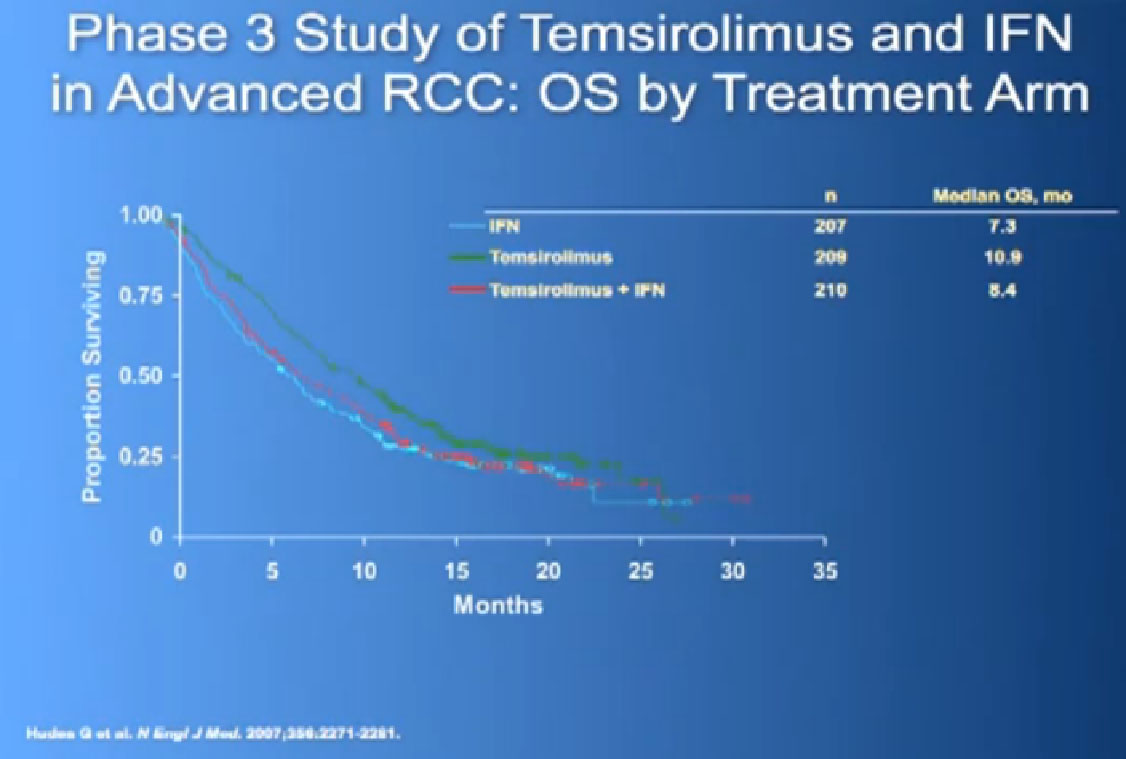

It is a bit difficult to see in the background, but bottom line, that this was the first drug that showed in poor risk patients, that it improved overall survival, compared to interferon. Does that mean Torisel is good for people who have good risk features? Those who don’t have overall poor risk factors? Unfortunately, we don’t have an answer to that since that study has not been done. But this drug was approved, and we know that Torisel seems to provide benefit for patients with the poorest features.

SLIDE MAY BE MISSING

Does that mean that Torisel shouldn’t be used in a second line treatment where people have clear cell? No, it doesn’t. It simply means that those are the data that we have, and in the second, and third and fourth line setting—except for the data I am now going to present—we just have to figure out. “You’ve been on this, we’ve tried that, now let’s try this.” There’s a certain amount of art to it, as well as science. Also known as Afinitor

Also known as Afinitor

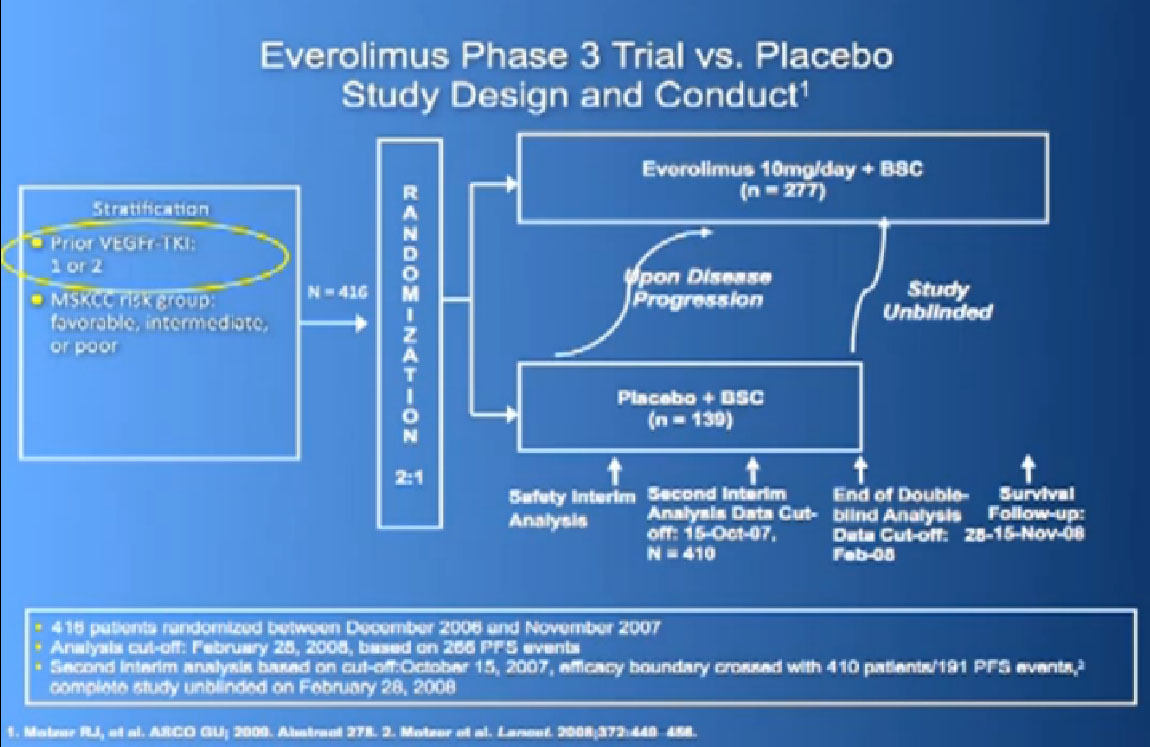

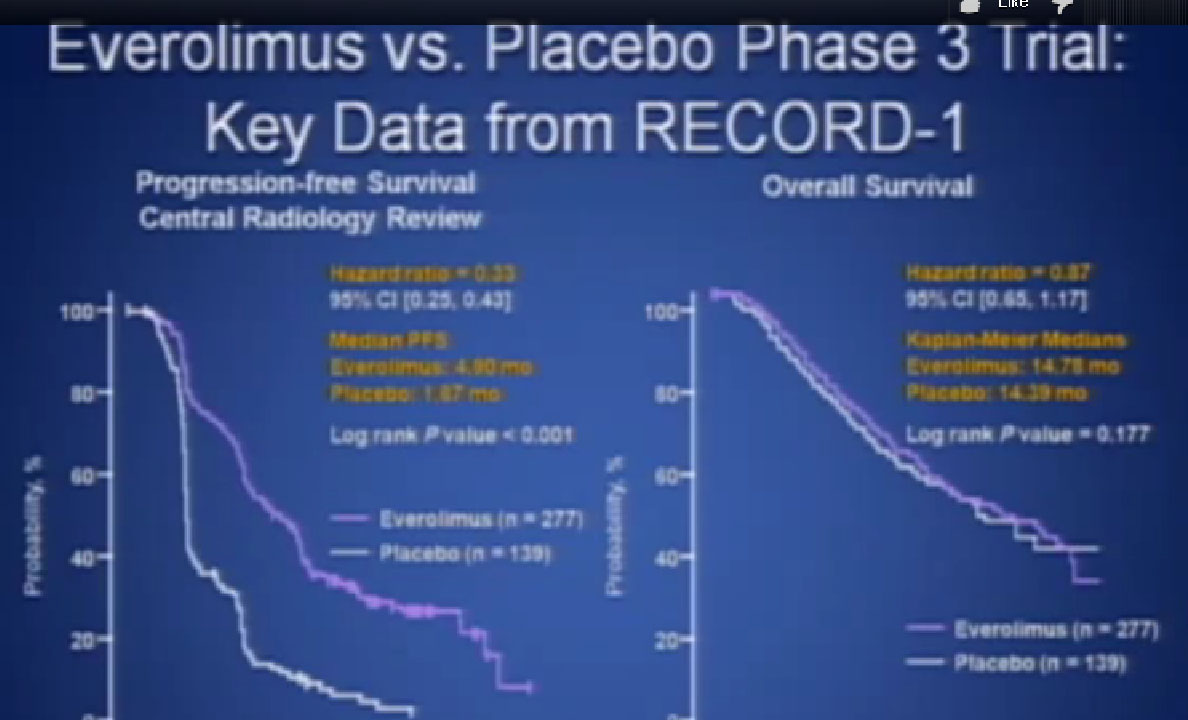

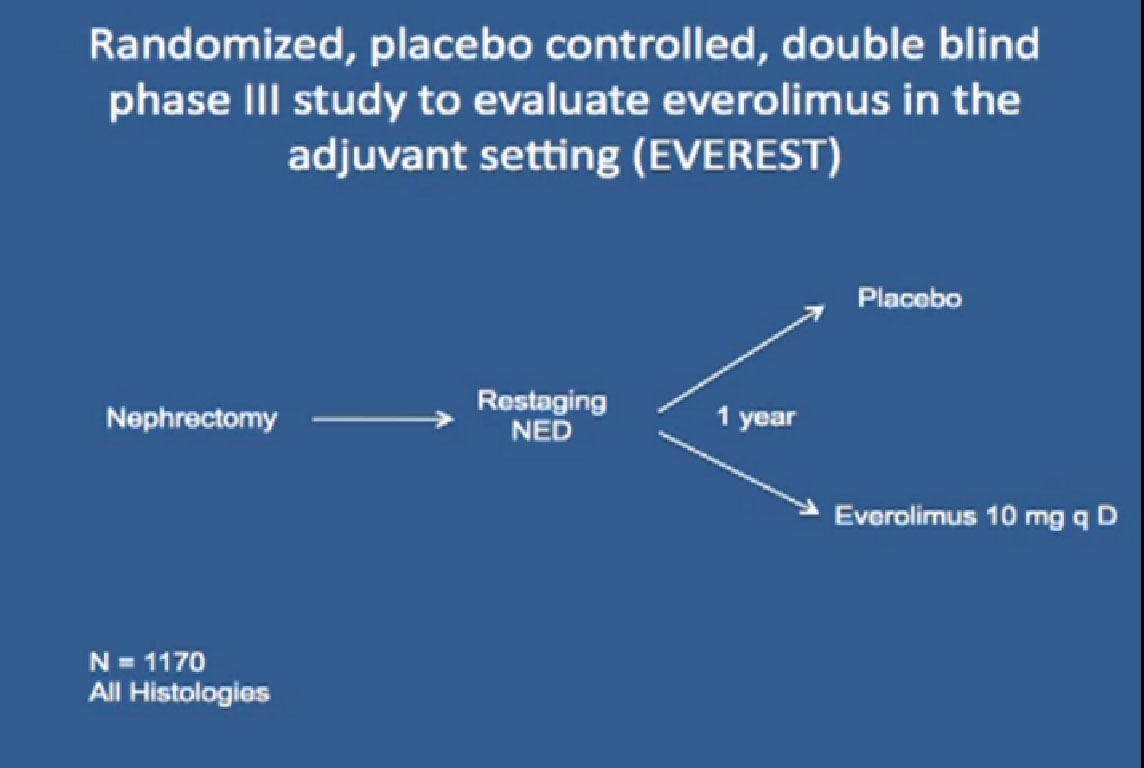

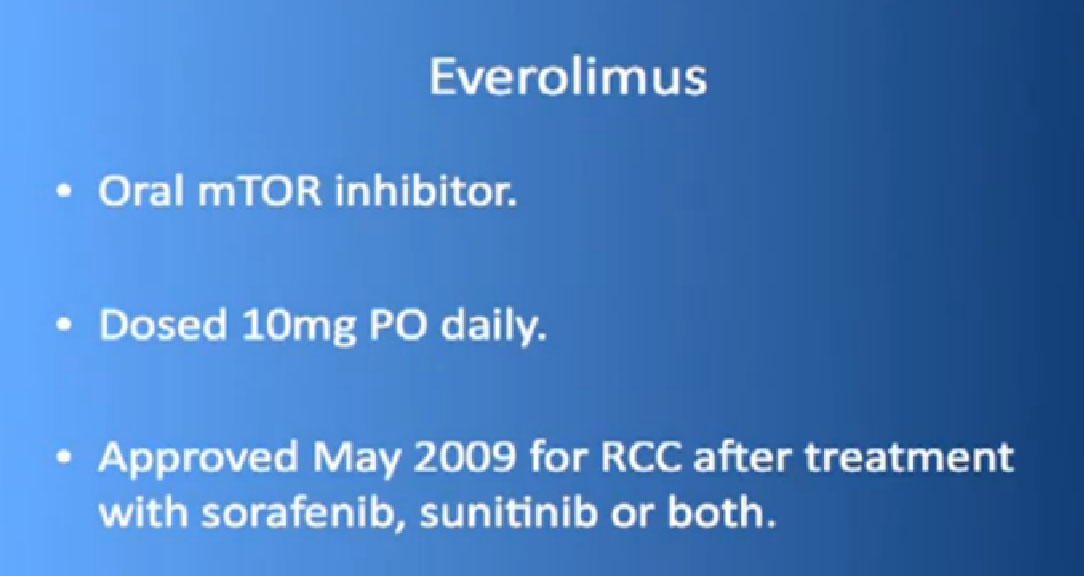

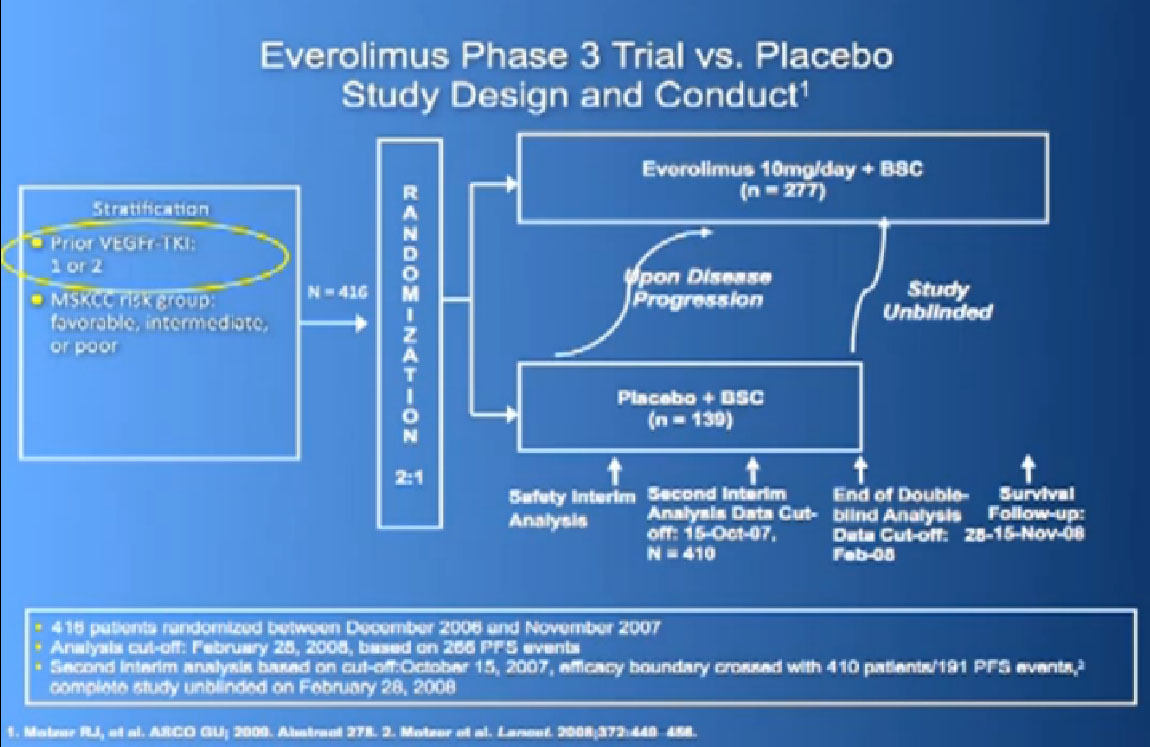

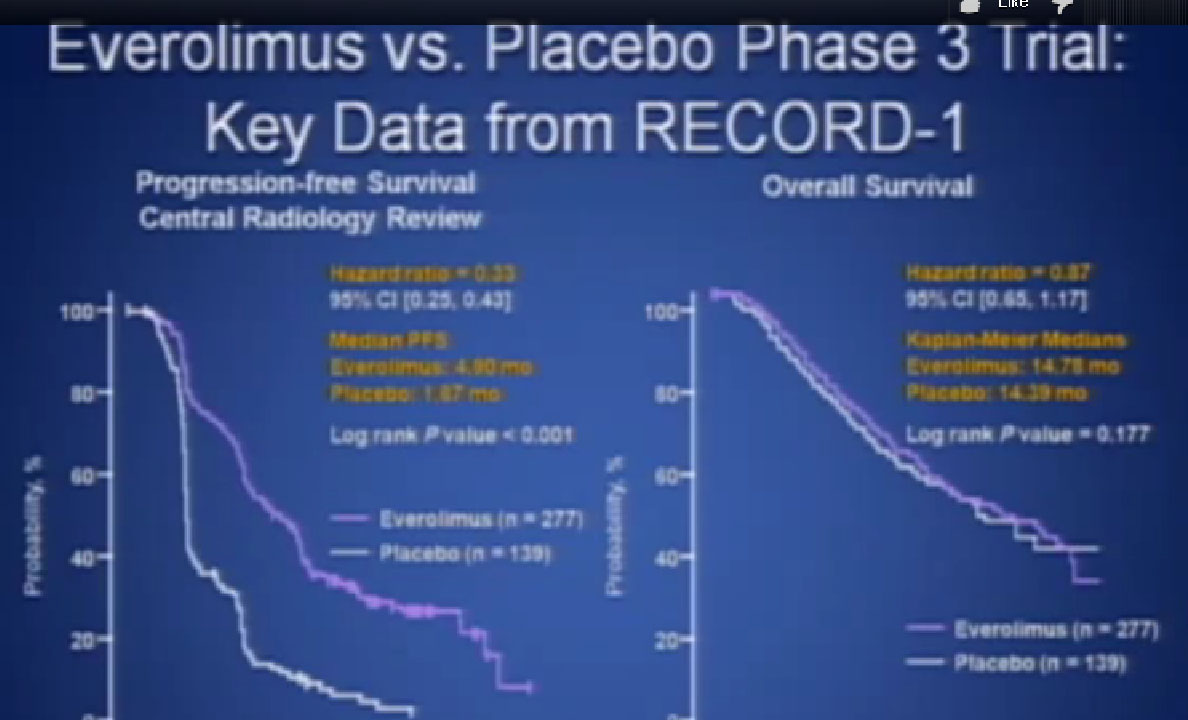

Afinitor was approved in 2009 for individual who had received either sutent, sorafenbit or both. This was a study that asked, “Have you progressed on Sutent or Nexavar?”

If yes, you were entered into the trial, randomized,ie the computer flipped a coin so that you went into the Afinitor or placebo, and we asked, “What was the progression free survival?”

This was clearly better in terms of progression free survival. And that’s why the drug was approved, and it is one of the most commonly used drugs in the second or third line for patients with metastatic kidney cancer.

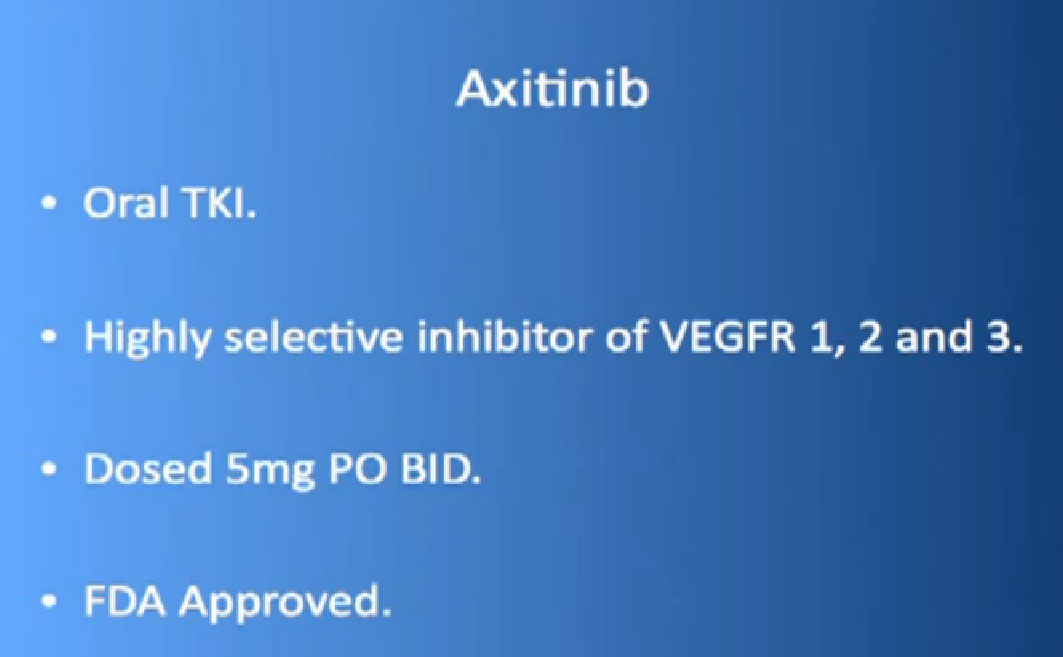

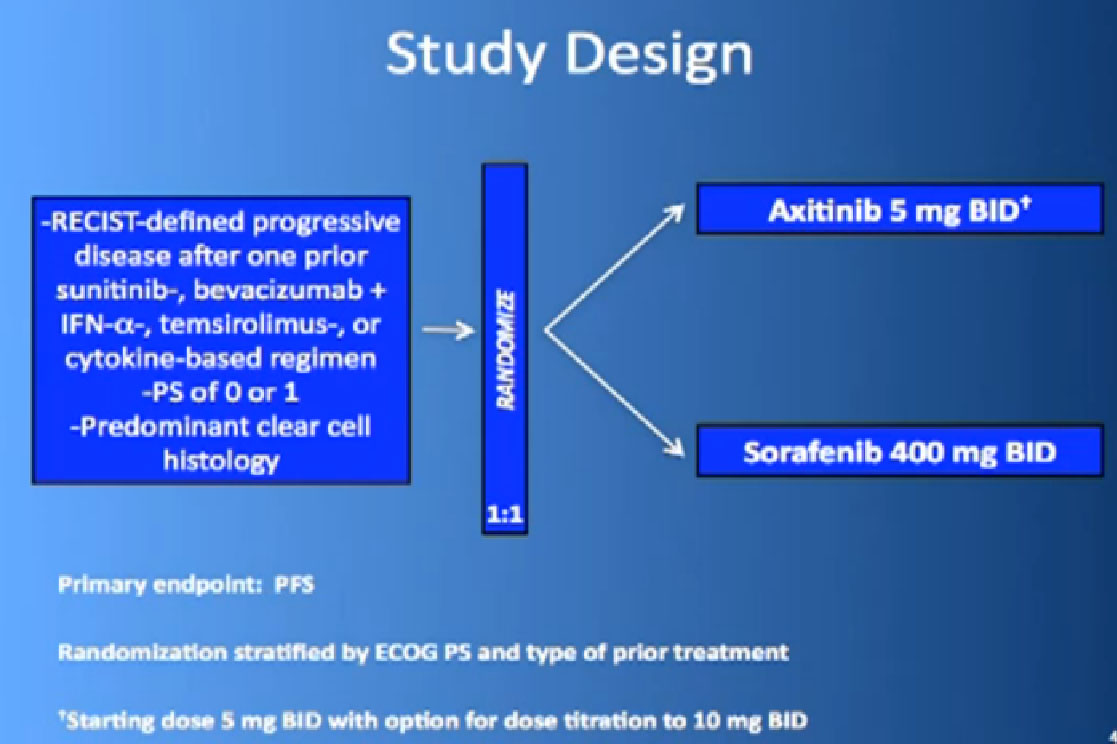

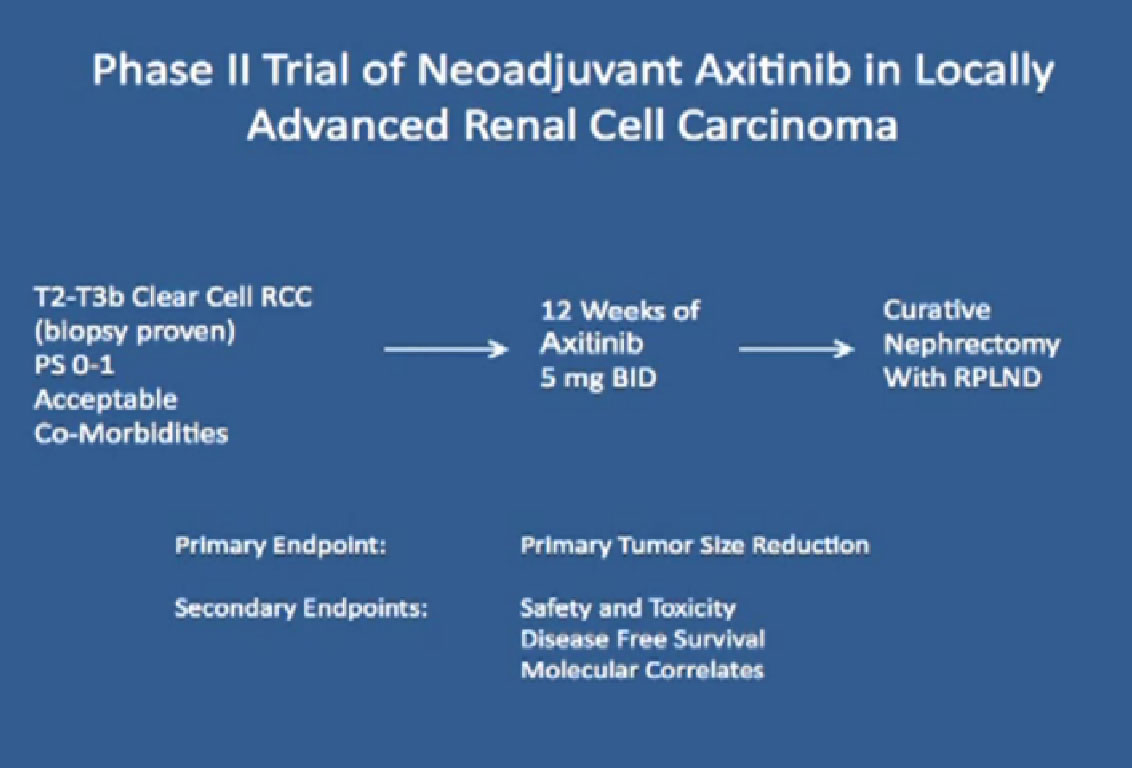

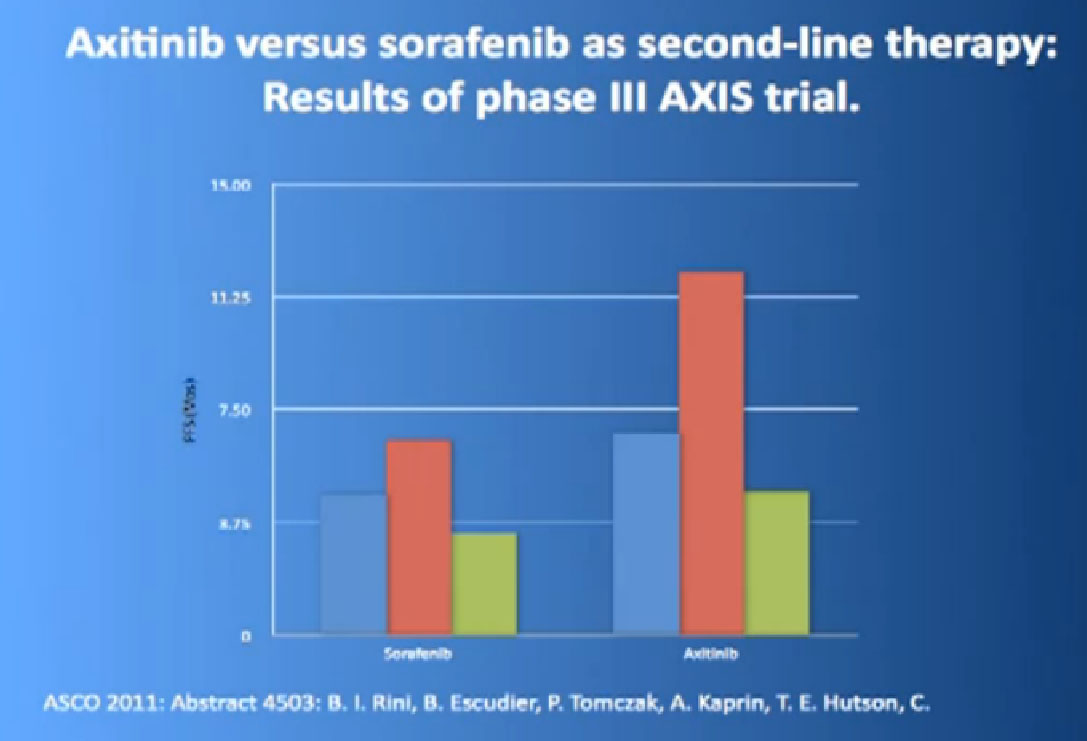

The new kid on the block is Axitinib or Inlyta, in the second line setting. Dr. Brian Rini presented these data last year, looking at this, another blood-vessel starving drug. It’s the next generation, it’s more highly engineered to block more of the VEGF pathways, and it does less of the other stuff, which in some ways might be better, but you might want to have some “playing the field” in terms of stopping things in comparison of blocking one thing. So what did this data show?

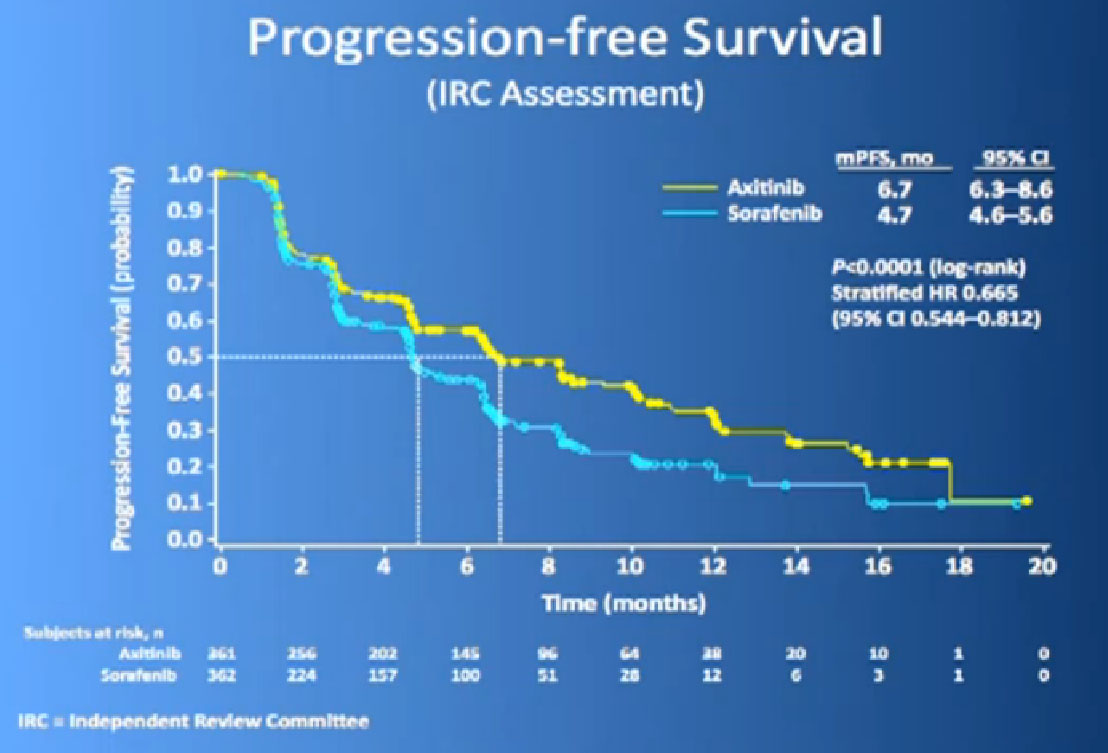

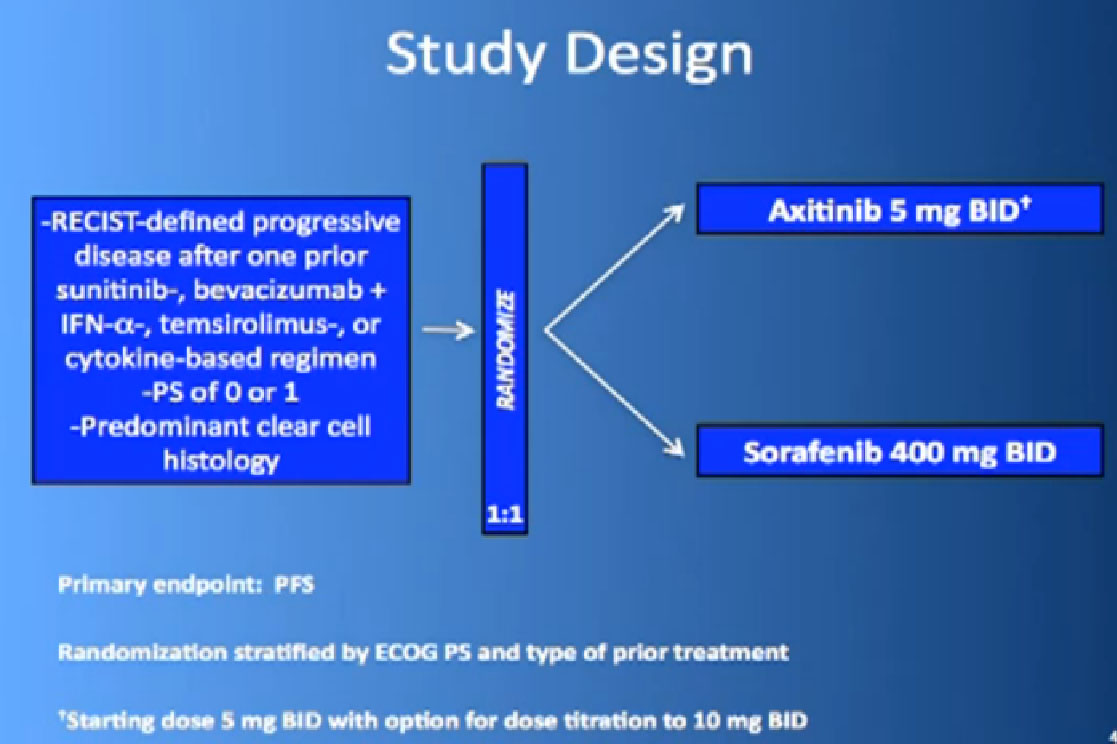

This is the study. People had previously received one of these prior drugs, Sunitinib, Bevacizumab, interferon, Temsirolimus or Cytokine, and then they looked at the progression free survival.

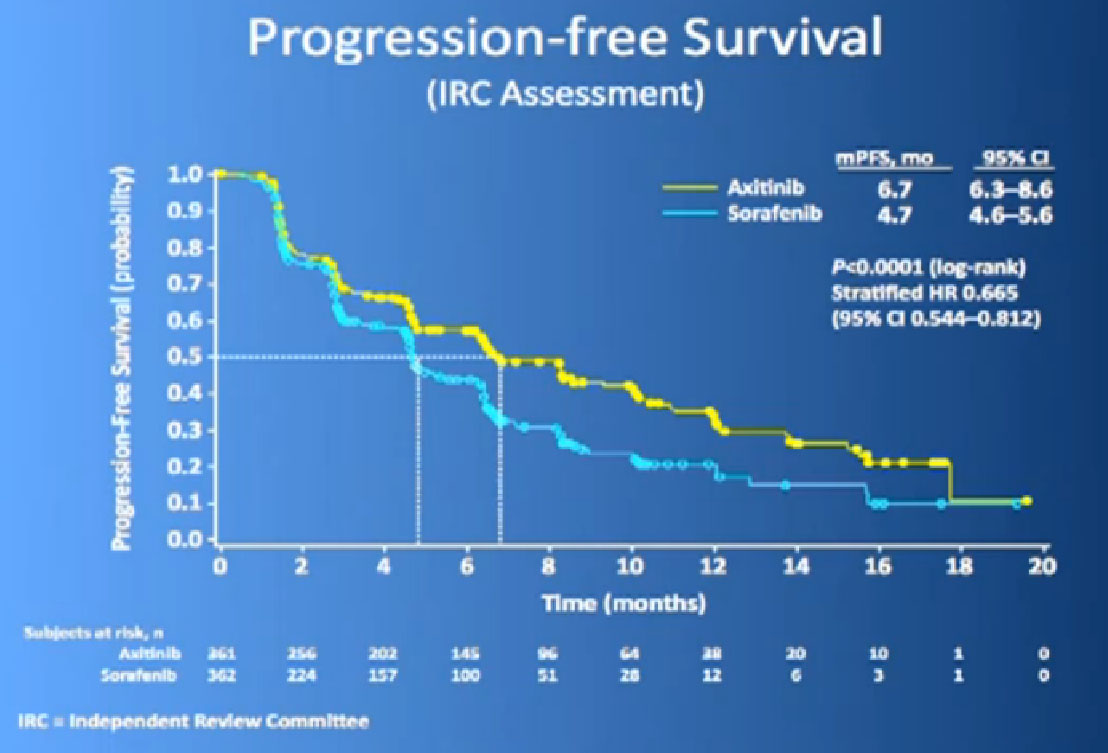

The progression free survival was longer in the Inlyta(Axitinib) group compared to the Nexavar (Sorafenib), about 6.7 months versus 4.7 months.

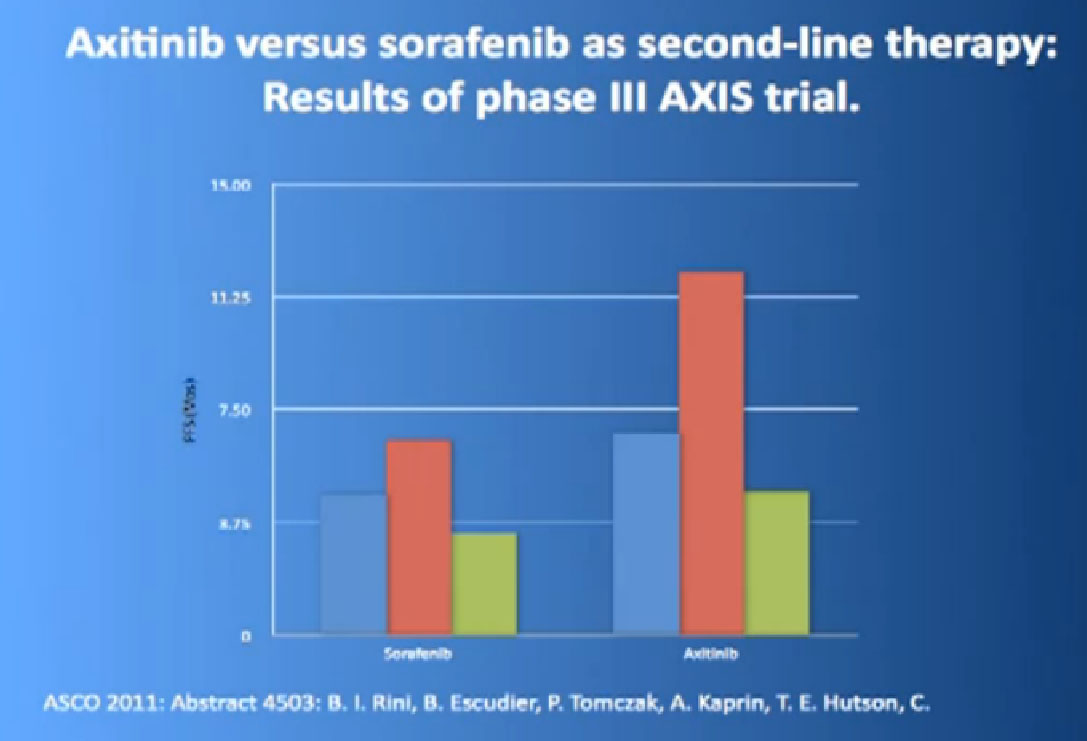

What was interesting, was this was a group of individual who had receive either these targeted drugs before or immune therapy, and it shows it nicely in table form, but what it shows is that if you had received prior immune therapy, the Axitinib or Inlyta was way better than the Nexavar. If you had received prior targeted therapy, in the same class as Inlyta, then the differences were not that great. Then it’s better, the Nexavar is better in people previously treated with Sutent, for example, but its not incredibly better, but it’s a clean drug, and it’s very welcome addition to the drugs we have available. So we are using it and getting good results.

Up and comers. For the last few minutes we will show Tivozanib, another one of these blood vessel starving drugs. So we have 1,2,3,4,5, and now six of the same class, and like other classes of drugs, it is always good to have gradual improvement. It is in a pill form, same sort of thing, blocking VEGF pathways. There were some combinations, a phase III trial, showing that it does actually do better than Nexavar it was compared to, and is coming down the pipeline, probably an approved drug in the next year.

It is interesting that with all of these drugs, that the newer the drug, the lower the side effect profile as they are getting better and better at engineering these drugs, so at least we are getting a better drug in this class arena. But it is not dramatically better, and we need something better.

Combinations and Sequences

So what about combinations? In oncology, we like to do this, combine drugs. If you have drug A and that works and you have drug B and that works, then let’s combine it and hope we get a duplicative effect, and additive effect. Hasn’t really happened unfortunately.

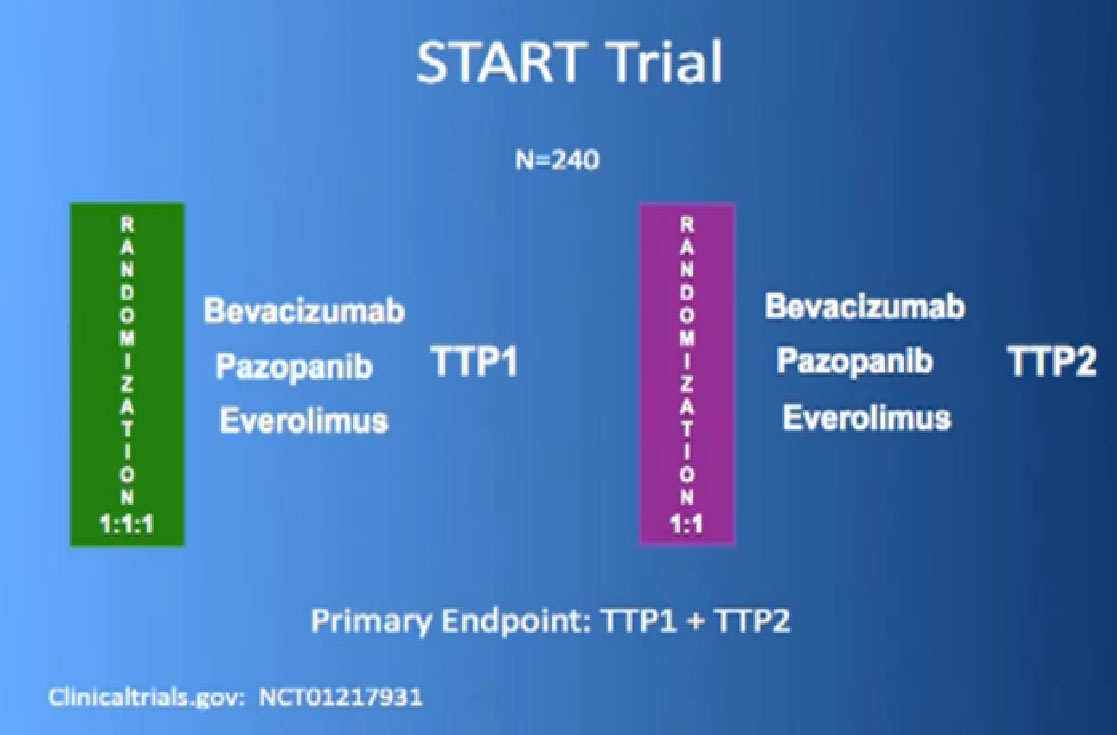

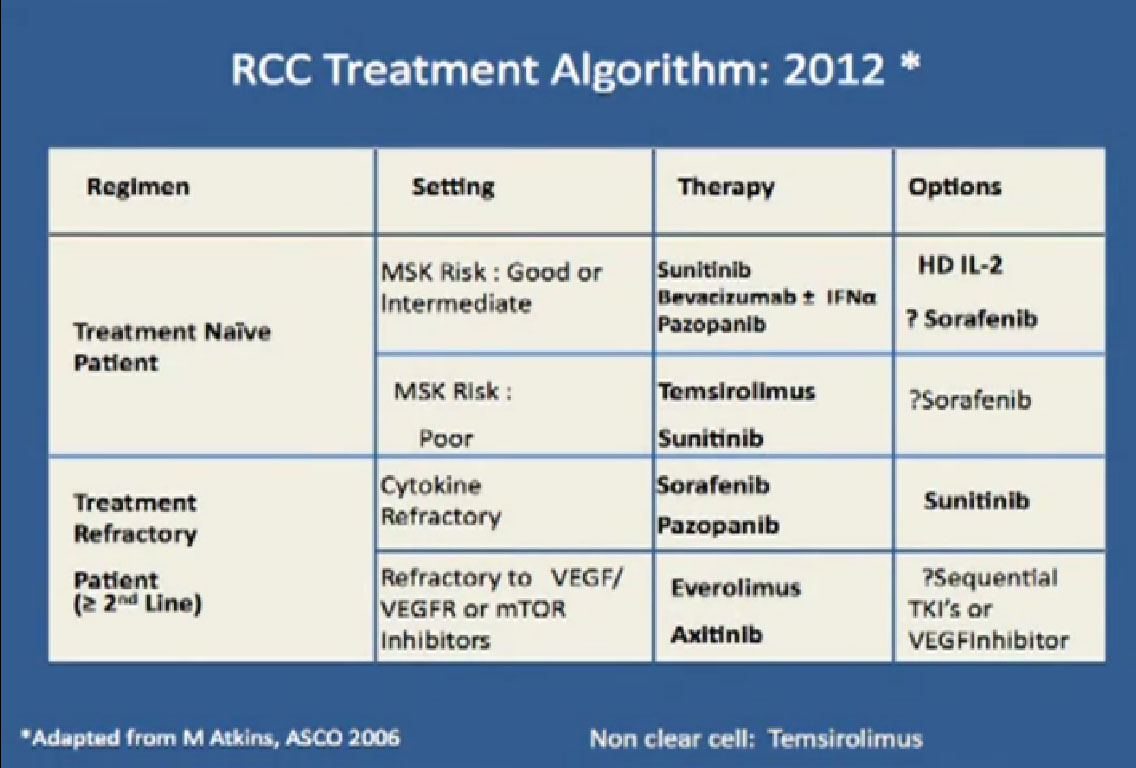

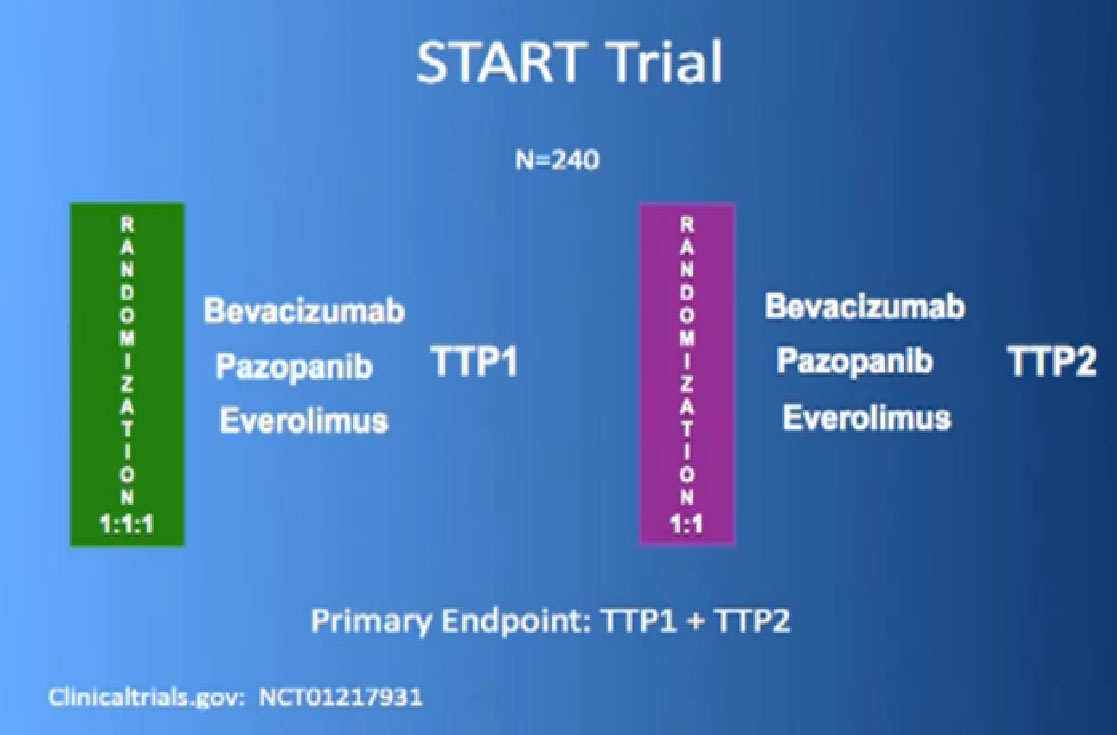

Bottom line. Combinations at that time have not really consistently been shown to be superior to single agents. You get more side effects and you don’t get more bang for the buck in terms of survival or progression. Sequencing is really what we do, meaning you start with drug A and move to drug B, you move on to drug C. That’s what we do in the clinic. One of the trials that Dr. Tannir has championed is the START trial and we have 80-90 patients on this.

We re looking at, if you start with Nexavar or Votrient or Avastin, and you get randomized to one of the remaining drugs, does that provide you better benefit?

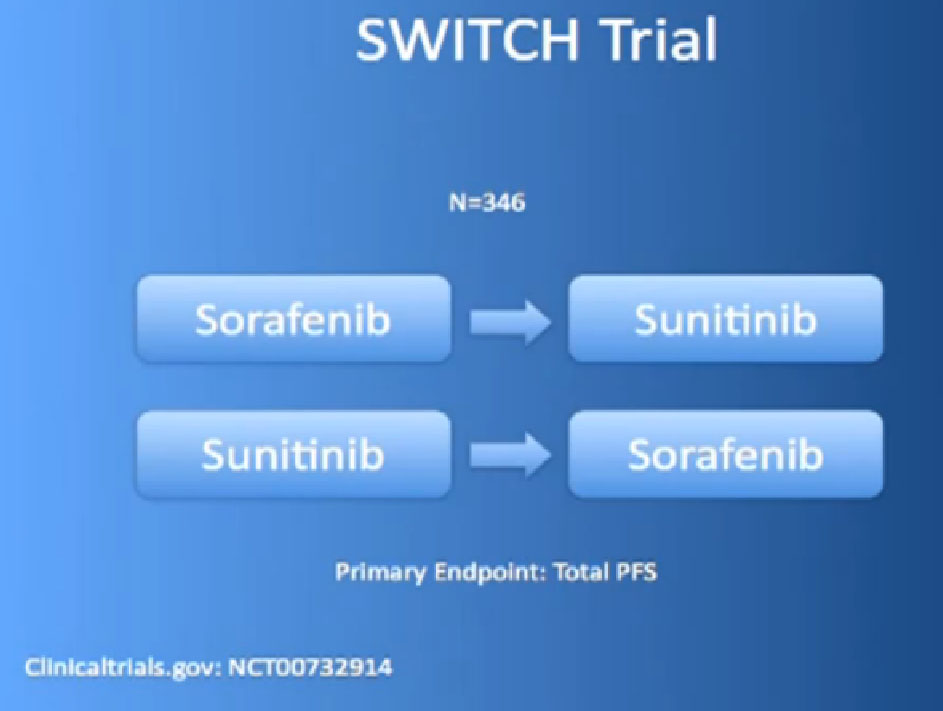

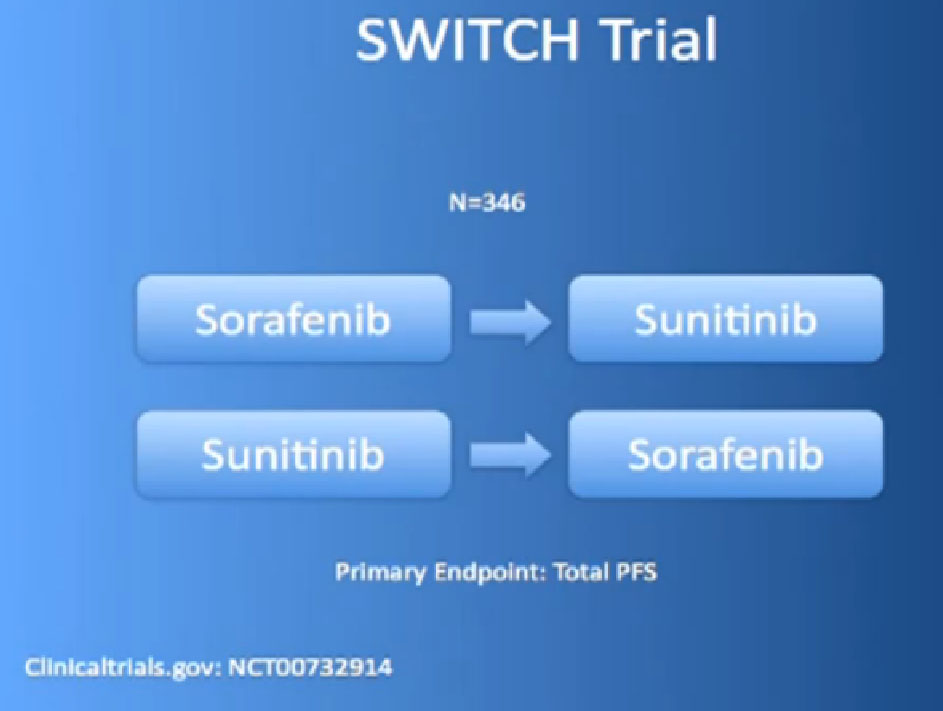

And there are other trials ongoing like that, the SWITCH trial, for example, going on in Europe, starting with Nexavar, then going to Sutent, or starting with Sutent and going on to Nexavar.

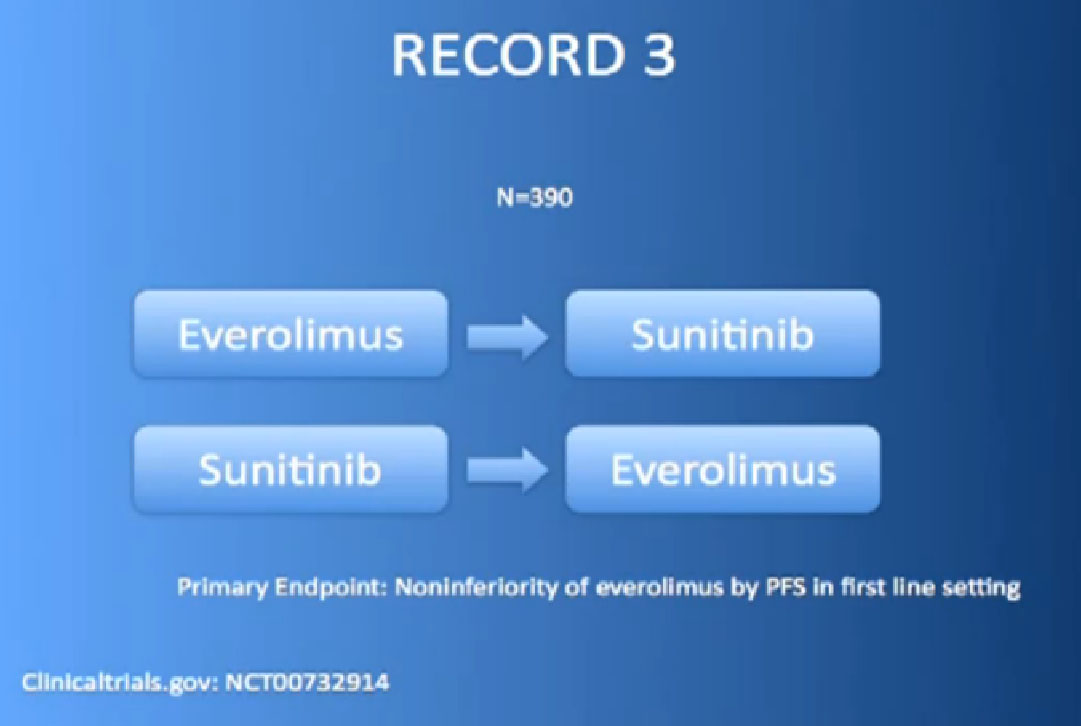

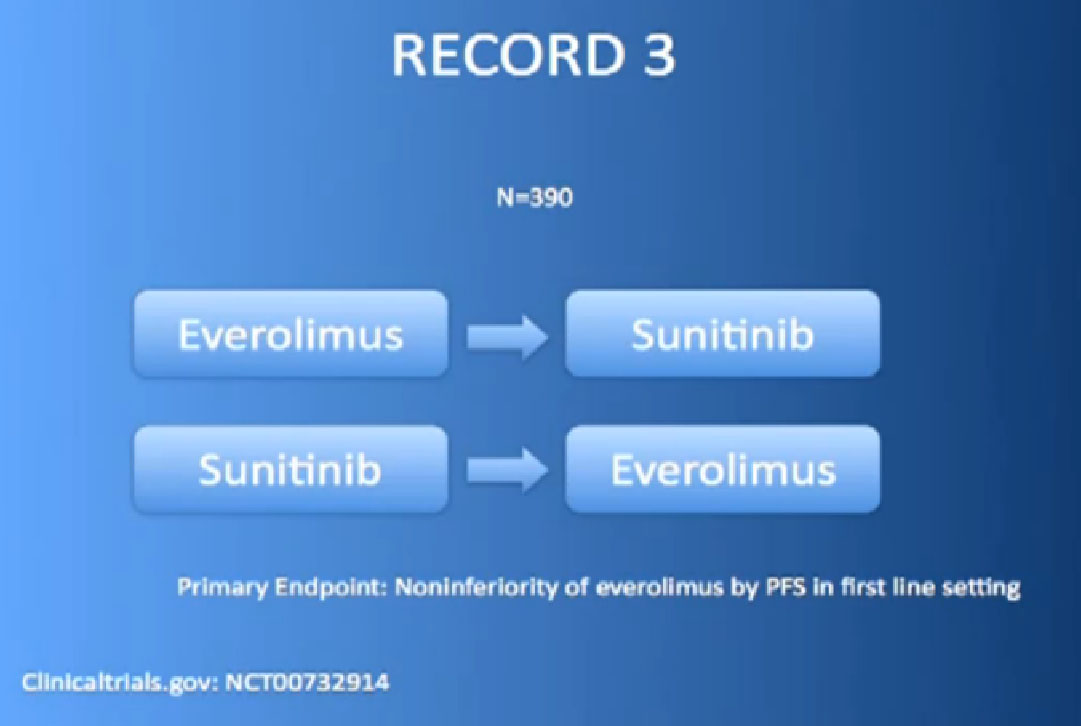

Or the RECORD 3 trial, with Afinitor followed by Sutent, or Sutent followed by Afinitor. We’re trying to figure out whether that works better for some patients than others.

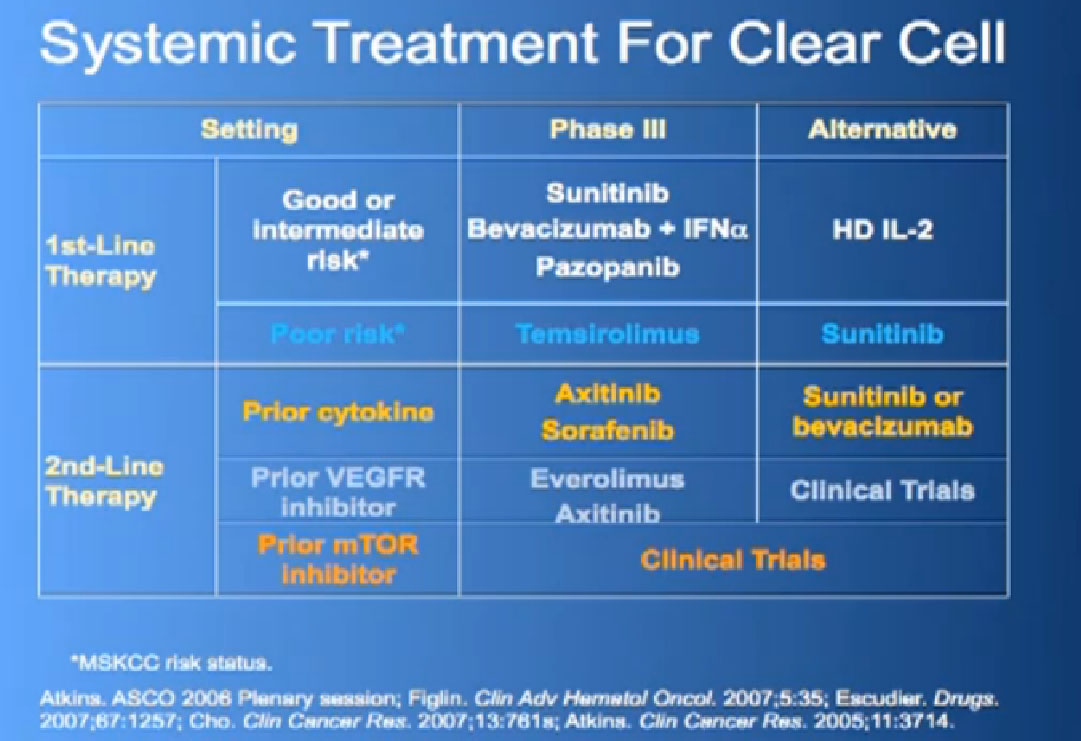

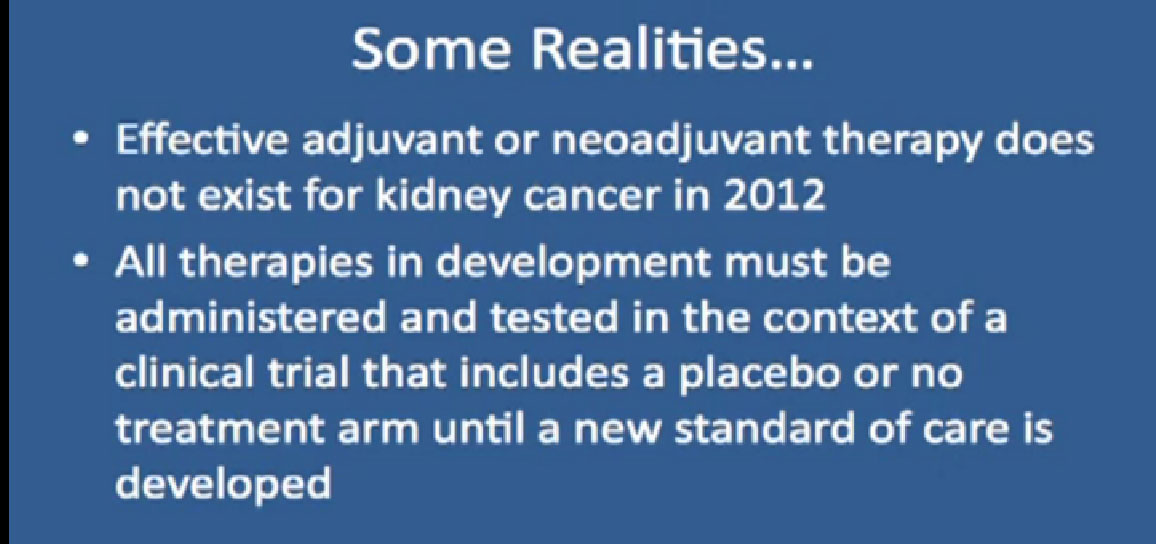

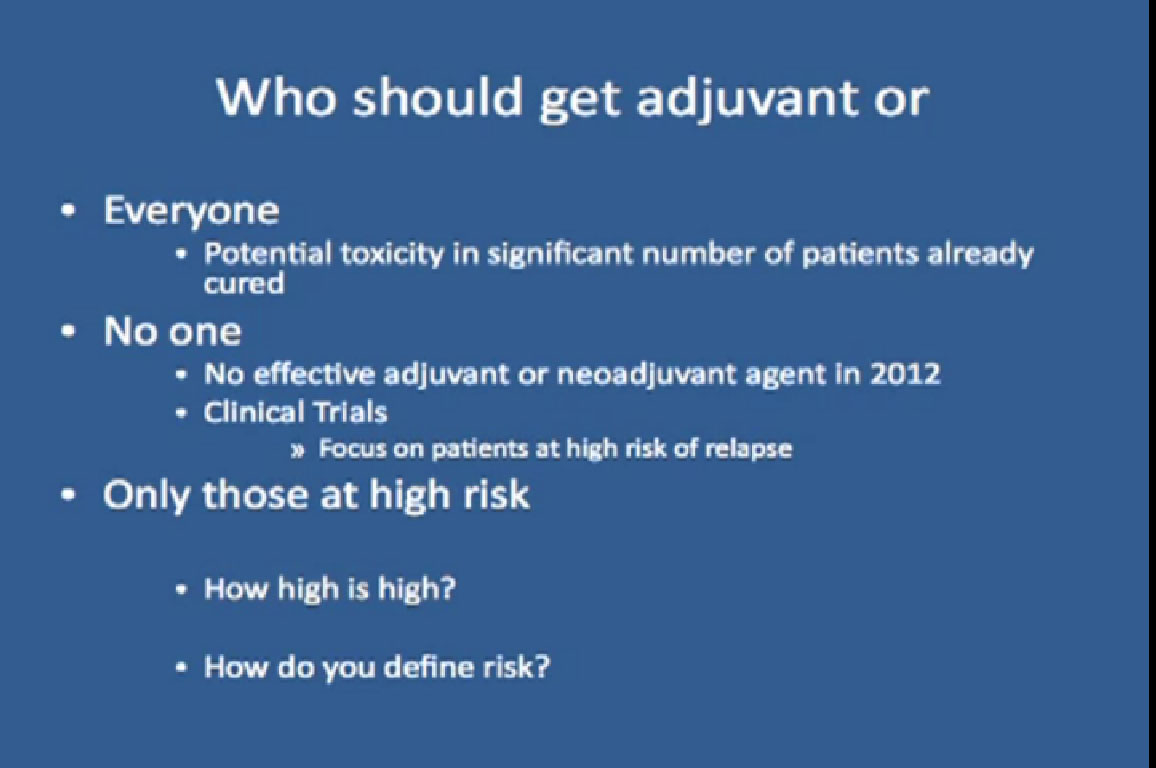

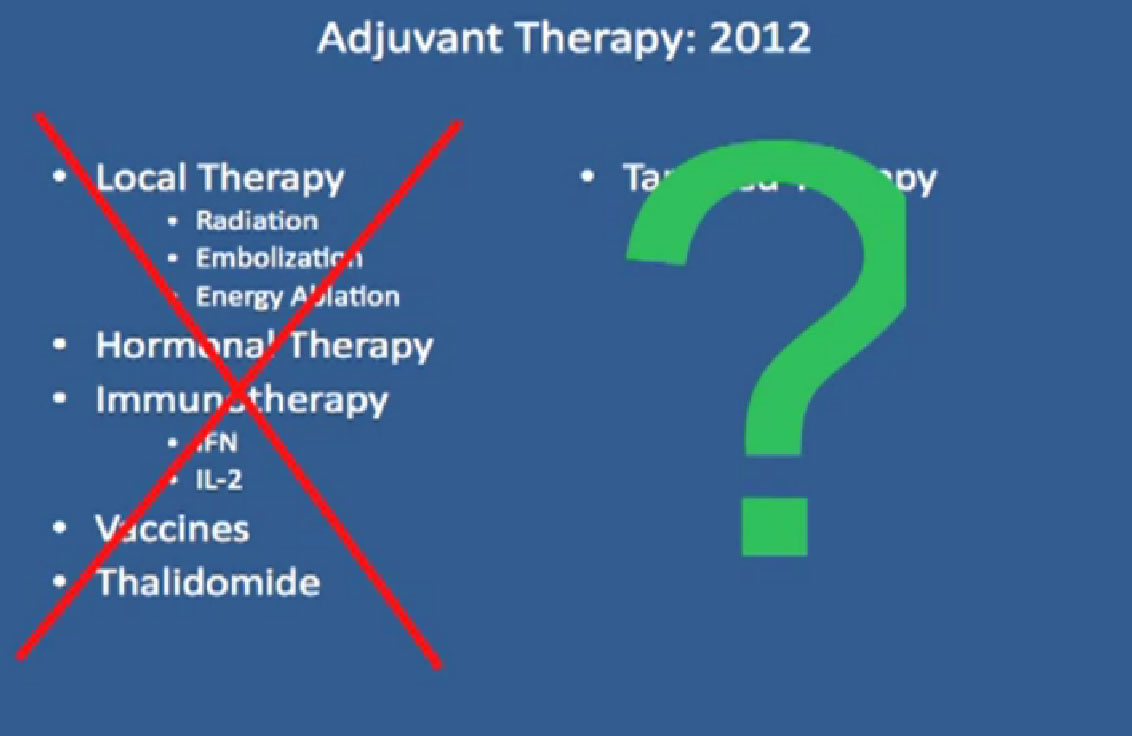

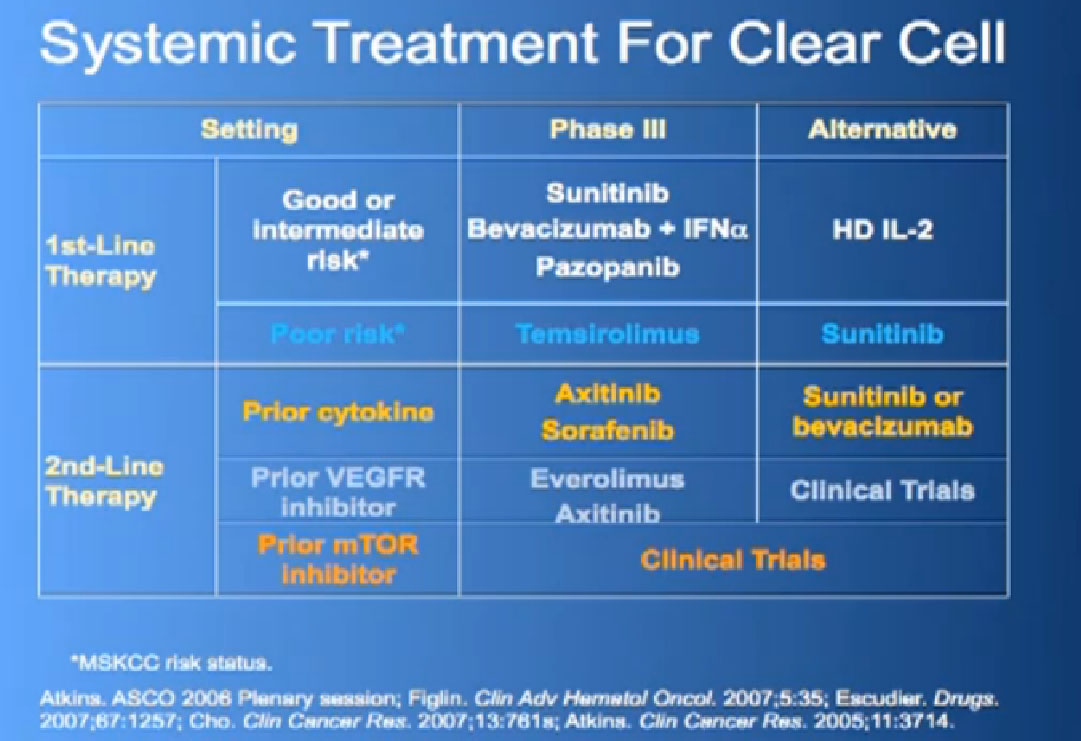

This is a big table put up my former mentor Dr. Michael Atkins, a form thereof in 2006, and its been a gradually refined over the years. Bottom line is we have favorite drugs for untreated patients in the first line setting. We talked about immunotherapy before lunch, with Dr. McDermott talked about interleukin 2 and others, we have our blood vessel-starving drugs for that category as well. People with poor risk features, we have Torisel.

In the second line setting we now have good data from these trials that show that Afinitor and Axitinib probably provide benefit after failing these other drugs, and we have ongoing studies to try to determine whether or not one sequence is better than another. All this is nice, and we’re making real strides, but what do we really need to do?

Coming back to the picture of the cancer, we are good at hitting the red part, (the blood vessel structure), but why, when they get used, are we getting resistance after 10-12 months or so. Why can’t we kill the cancer cells?

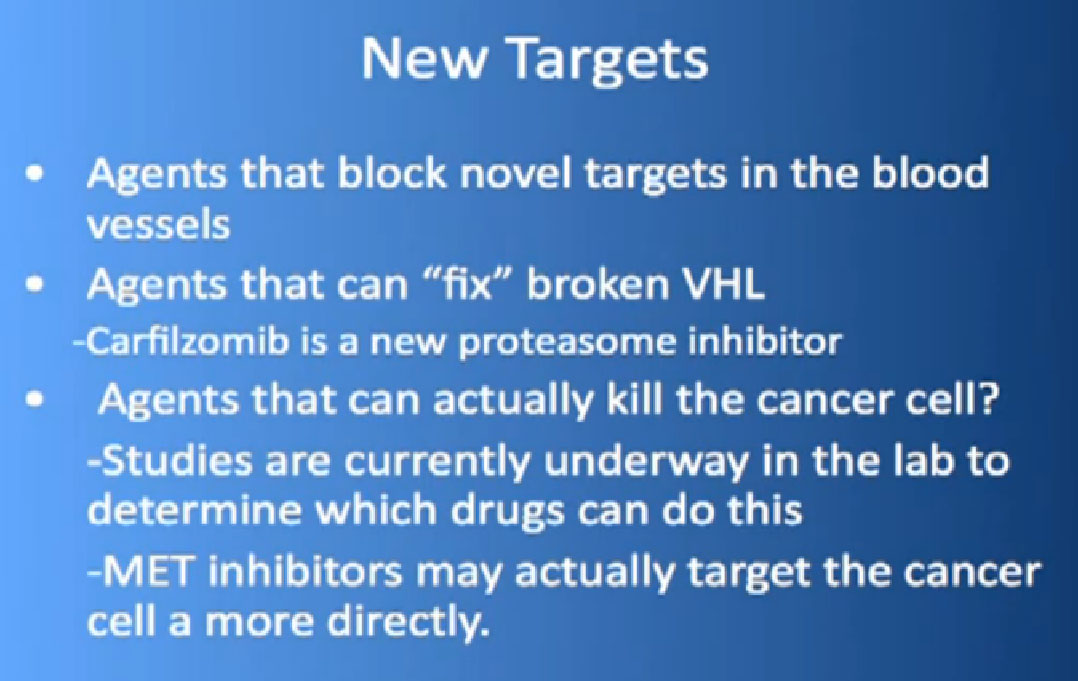

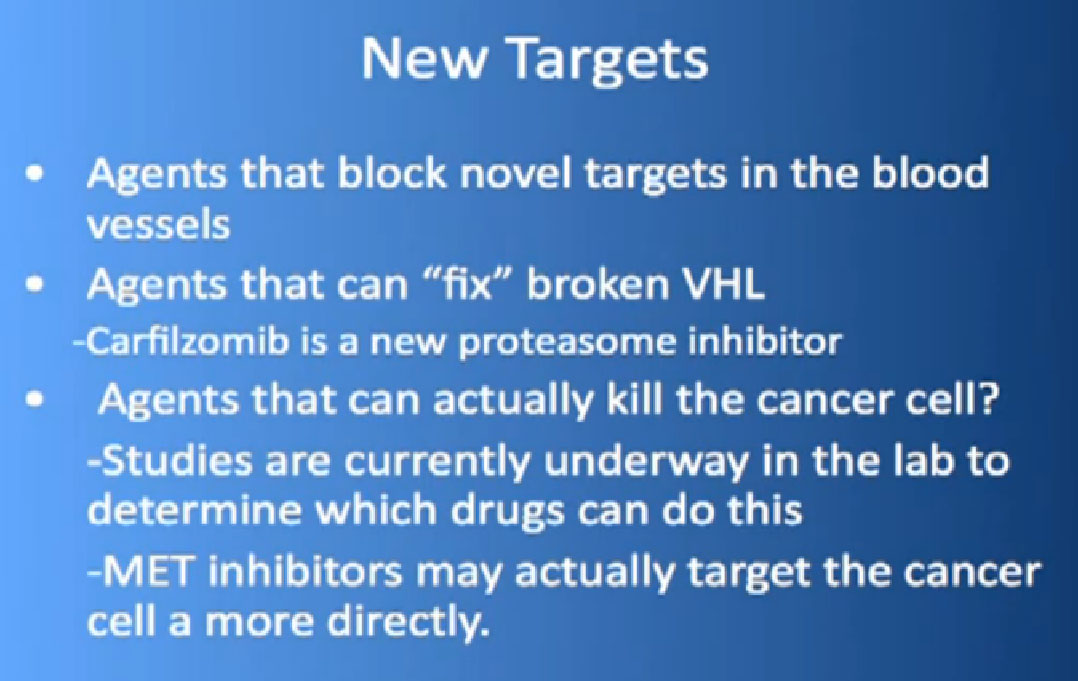

We need new drugs that can block other receptors in those blood vessels cells. We need agents that can actually fix, look under the hood of the cancer cell, see what is misbehaving there, fiddle with it, and make it act more like a normal cell. If we can’t do that, kill the cancer cell. Agents that can actually block novel targets in the blood vessels, so we are looking at new receptors on there, and seeing if those drugs, in combinations with other drugs, can starve the blood vessels, are useful.

I am part of a nano-medicine grant, where the hypothesis is that, the big idea, is that a lot of the VHL proteins are mutated, are kind of wounded, but not dead. If we can revive them, maybe they can make the cancer cell behave more normally. One of the ways to do that, to raise the level of VHL, is with a drug called Carfilzomib to validate that.

MET Inhibitors

The last thing is those agents that can actually kill the cancer. This is amazingly, in 2012, still in the experimental stages. We have a colleague in Stanford, Imato Jatia(?) who has done some of these screens, some people at Harvard, all around the country, and we as well, looking at this strategy, where the cell kills itself. We have go to perhaps stop focusing as much as getting as yet another blood vessel-starving pill. An example of one of these drugs that might do this, is a MET inhibitor. So, a MET is another protein that is found on the surface of the Cancer cell. There were some reports at ASCO that this might a promising avenue.

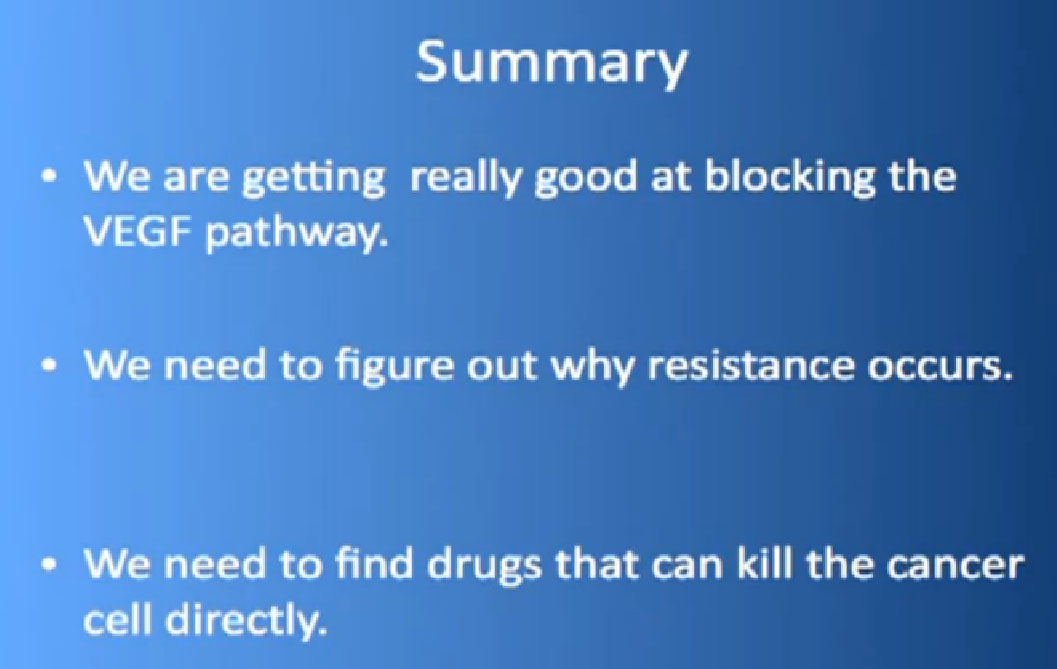

So in summary, we are getting really good at blocking VEGF pathway, we’ve made real inroad in Overall Survival. MTOR inhibitors are doing a good job; we kind of know where to use these, but we are getting better at it. We have got to figure out why resistance occurs, and do something about it. Participation in clinical trials is key. We need to find drugs that kill the cancer cell directly.

QED

Also known as Nexavar

Also known as Nexavar

Also known as Afinitor

Also known as Afinitor